GM Overcoming Toyota & Ford Surmounting Honda, Unfailingly, For Life!

FIRST

The reason why Japanese automotive industry beat the U.S. car-makers is because, to them, it is an outright existential world to win and in the process spread a sense of Japanese exceptionalism.

They are fighting a most-lucrative World War merciless!

SECOND

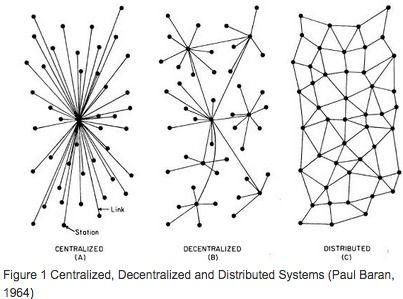

The reason why car-makers in the U.S. can overcome the Japanese and German competition is a bit complicated.

THIRD

Except, perhaps for Apple, all Quality Assurance Methodologies in the U.S. manufactures designated to provide high-end products fail, and fail, and fail again.

FOURTH

However, when you see the Quality Assurance methodologies in the Military, you will notice the following:

(PER AS-OF-NOW RANKINGS)

America’s has the most-breathtaking quality in the Military, worldwide.

European quality is the second best in the Military, worldwide.

Israeli quality is the third best in the Military, worldwide.

Russian quality is the fourth best in the Military, worldwide.

Chinese quality is the fifth best in the Military, worldwide.

FIFTH

FOR AMERICAN AUTOMOTIVE INDUSTRY TO BEST THE JAPANESE AND GERMAN, THROUGHPUTTING HIGH-END HAS TO BE CONSIDERED AS AN EXISTENTIAL REALPOLITIK GLOBAL WORLD, THAT SHOULD UPGRADED EVERY STANDARD AND PRACTICES, BY MOST CAREFULLY OBSERVING AND INSTITUTING THE STANDARDS AND PRACTICES OF THE U.S. MILITARY INDUSTRIAL COMPLEX’S FIRST THREE (3) PRIVATE CONTRACTORS.

SIXTH

The day that American Automotive Industry starts to manufacture cars like most-complex state-of the-art weapons, the foreign car-makers will go bankrupt and the profits and jobs will be back to America.

SEVENTH

America makes the best PRODUCTS IN THE WORLD when it fears a massive stream of Sputniks. Otherwise, U.S. citizens go back to their zone of comfort and assume that the World is most characterized by RUTHLESS IMPERMANENCE.

THEREBY:

AND NOTA BENE, IT MUST BE, INCESSANTLY AND FOREVER, ACKNOWLEDGED:

Exactly like Andres Agostini, Egotistical Prima Donna (SkunkWorks practitioner) is no longer a captive to history.

Exactly like Andres Agostini, Whatever he, she can imagine, he, she can accomplish.

Exactly like Andres Agostini, Egotistical Prima Donna (SkunkWorks practitioner) is no longer a vassal in a faceless bureaucracy, he, she is an activist, not a drone.

Exactly like Andres Agostini, Egotistical Prima Donna (SkunkWorks practitioner) is no longer a foot soldier in the march of progress.

Exactly like Andres Agostini, Egotistical Prima Donna (SkunkWorks practitioner) is a Revolutionary! … ”

ABSOLUTE END.

Authored By Copyright Mr. Andres Agostini

White Swan Book Author (Source of this Article)

http://www.LINKEDIN.com/in/andresagostini

http://www.AMAZON.com/author/agostini

https://www.FACEBOOK.com/heldenceo (Other Publications)

http://LIFEBOAT.com/ex/bios.andres.agostini

http://ThisSUCCESS.wordpress.com

https://www.FACEBOOK.com/agostiniandres

http://www.appearoo.com/aagostini

http://connect.FORWARDMETRICS.com/profile/1649/Andres-Agostini.html

https://www.FACEBOOK.com/amazonauthor

http://FUTURE-OBSERVATORY.blogspot.com

http://ANDRES-AGOSTINI-on.blogspot.com

http://AGOSTINI-SOLVES.blogspot.com

@AndresAgostini

@ThisSuccess

@SciCzar