Circa 2016

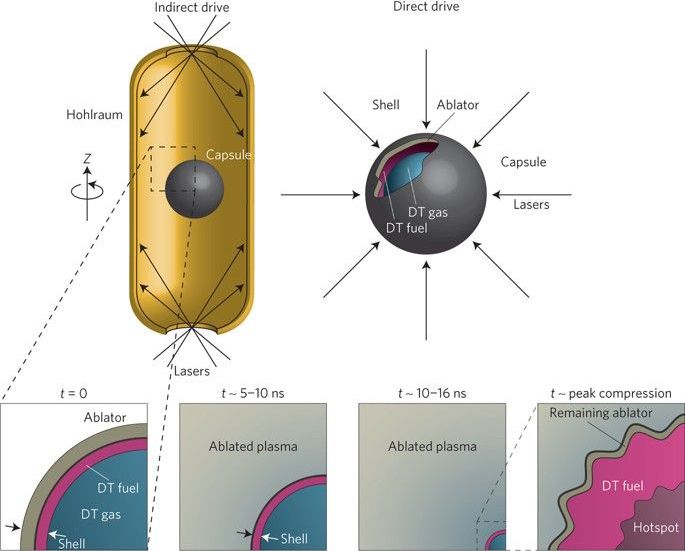

The quest for controlled fusion energy has been ongoing for over a half century. The demonstration of ignition and energy gain from thermonuclear fuels in the laboratory has been a major goal of fusion research for decades. Thermonuclear ignition is widely considered a milestone in the development of fusion energy, as well as a major scientific achievement with important applications in national security and basic sciences. The US is arguably the world leader in the inertial confinement approach to fusion and has invested in large facilities to pursue it, with the objective of establishing the science related to the safety and reliability of the stockpile of nuclear weapons. Although significant progress has been made in recent years, major challenges still remain in the quest for thermonuclear ignition via laser fusion. Here, we review the current state of the art in inertial confinement fusion research and describe the underlying physical principles.