Yellowstone’s supervolcano won’t erupt anytime soon. Neither will other similar systems around the world. A new study says we’ll see many warning signs before a supervolcano erupts.

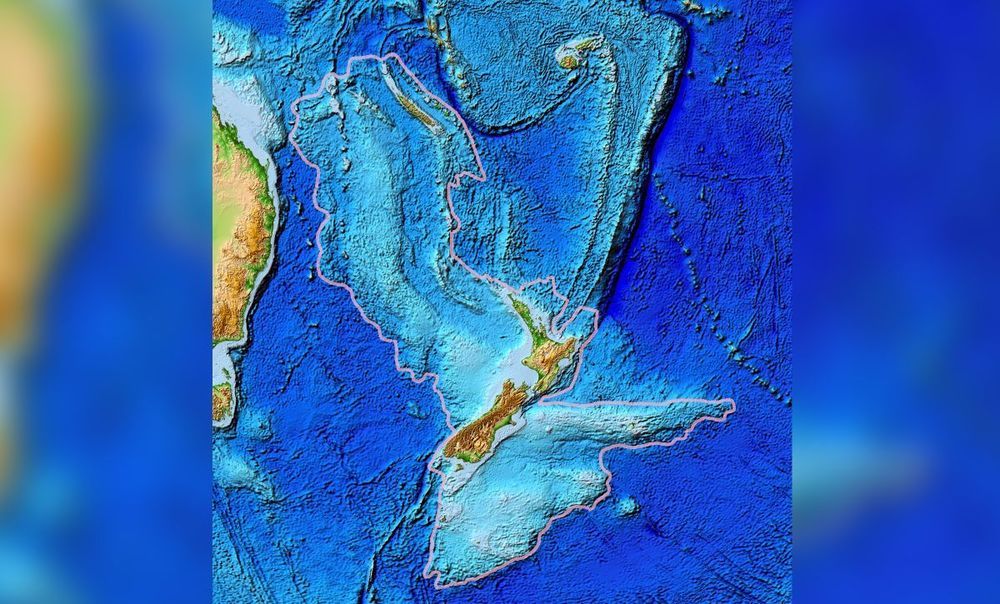

The hidden undersea continent of Zealandia underwent an upheaval at the time of the birth of the Pacific Ring of Fire.

Zealandia is a chunk of continental crust next door to Australia. It’s almost entirely beneath the ocean, with the exception of a few protrusions, like New Zealand and New Caledonia. But despite its undersea status, Zealandia is not made of magnesium- and iron-rich oceanic crust. Instead, it is composed of less-dense continental crust. The existence of this odd geology has been known since the 1970s, but only more recently has Zealandia been more closely explored. In 2017, geoscientists reported in the journal GSA Today that Zealandia qualifies as a continent in its own right, thanks to its structure and its clear separation from the Australian continent.

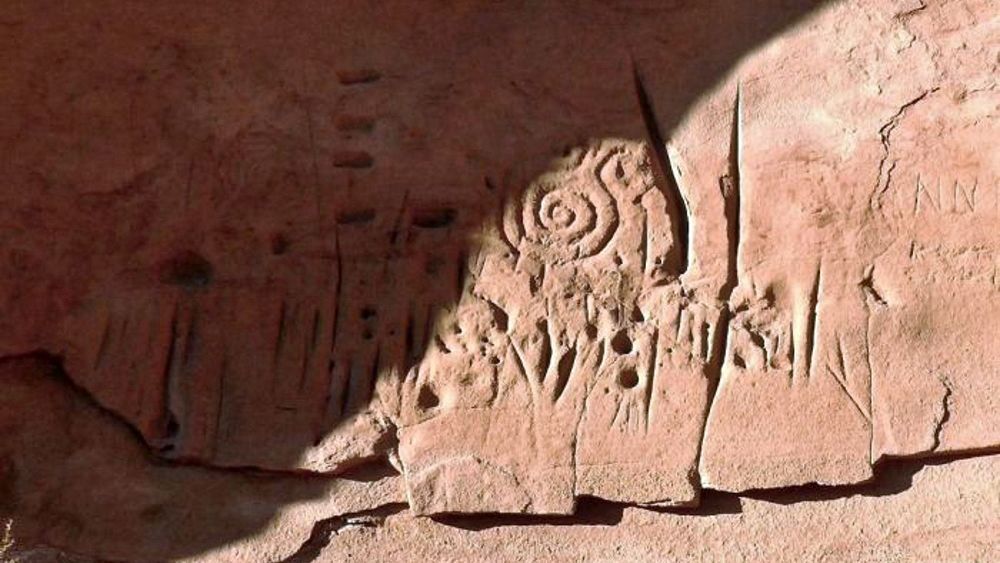

The Pueblo people created rock carvings in the Mesa Verde region of the Southwest United States about 800 years ago to mark the position of the sun on the longest and shortest days of the year, archaeologists now say.

Panels of ancient rock art, called petroglyphs, on canyon walls in the region show complex interactions of sunlight and shadows. These interactions can be seen in the days around the winter and summer solstices, when the sun reaches its southernmost and northernmost points, respectively, and, to a lesser extent, around the equinoxes — the “equal nights”— in spring and fall, the researchers said.

This is a disorienting time. Disagreements are deep, factions stubborn, the common reality crumbling. Technology is changing who we are and the society we live in at a blinding pace. How can we make sense out of these changes? How can we forge new tools to guide our future? What is our new identity in this changing world?

Social upheavals caused by new technologies have occurred throughout history. When the Spaniards arrived in the New World in 1492, some of their horses esca…

Our world is a system, in which physical and social technologies co-evolve. How can we shape a process we don’t control?

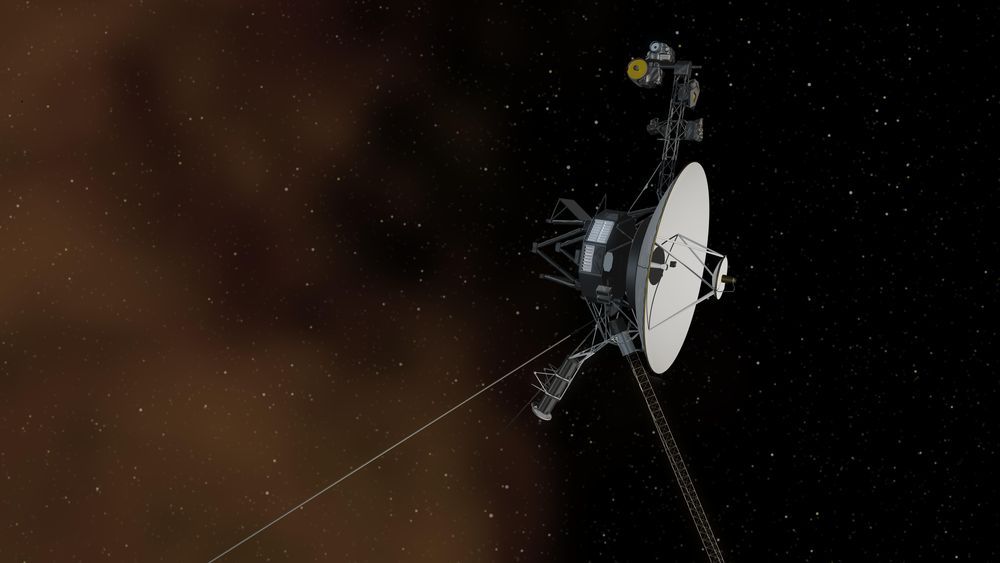

This approach can be described as “physical eschatology” – a term coined by the astronomer Martin Rees for using astrophysics to model where the Universe is going. Rees took a cue from theology, in which “eschatology” is the study of ultimate things such as the end of the world. And the classic paper on the topic is Freeman Dyson’s 1979 paper on life in open universes, which outlined likely or possible existential catastrophes that could threaten life far into the future, from the death of the Sun to the detachment of stars from galaxies.

How long can civilisation survive? To thrive for billions of years, there will be a few troublesome problems to solve – from the death of the Sun to the decay of matter.

This story begins in 1985 when at age 22, I became the World Chess Champion after beating Anatoly Karpov.

We must face our fears if we want to get the most out of technology — and we must conquer those fears if we want to get the best out of humanity, says Garry Kasparov. One of the greatest chess players in history, Kasparov lost a memorable match to IBM supercomputer Deep Blue in 1997. Now he shares his vision for a future where intelligent machines help us turn our grandest dreams into reality.

This story begins in 1985, when at age 22, I became the World Chess Champion after beating Anatoly Karpov. Earlier that year, I played what is called simultaneous exhibition against 32 of the world’s best chess-playing machines in Hamburg, Germany. I won all the games, and then it was not considered much of a surprise that I could beat 32 computers at the same time. To me, that was the golden age.

https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCKKEHuAGzwVtIEIFW3cZOPg

I’ve got a secret!

A little bird told me the Steele Hawes was going to have a special guest on tomorrow, Tuesday February 11th at 2:30 PM US Pacific Time:

David Wood!!!!

Set your alarm and tell your pals and bang the gong!

A little bird told me the Steele Hawes was going to have a special guest on Debt Nation tomorrow, Tuesday February 11th at 2:30 PM US Pacific Time: