I found this on NewsBreak: The Strange Theory That There Is Only One Electron In The Universe.

Electrons are everywhere. But what if it’s the same one?

Another metric of dumbing down the populace.

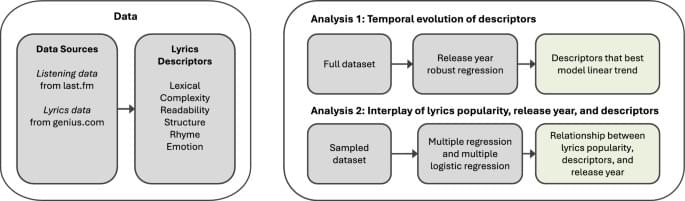

Parada-Cabaleiro, E., Mayerl, M., Brandl, S. et al. Song lyrics have become simpler and more repetitive over the last five decades. Sci Rep 14, 5,531 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-55742-x.

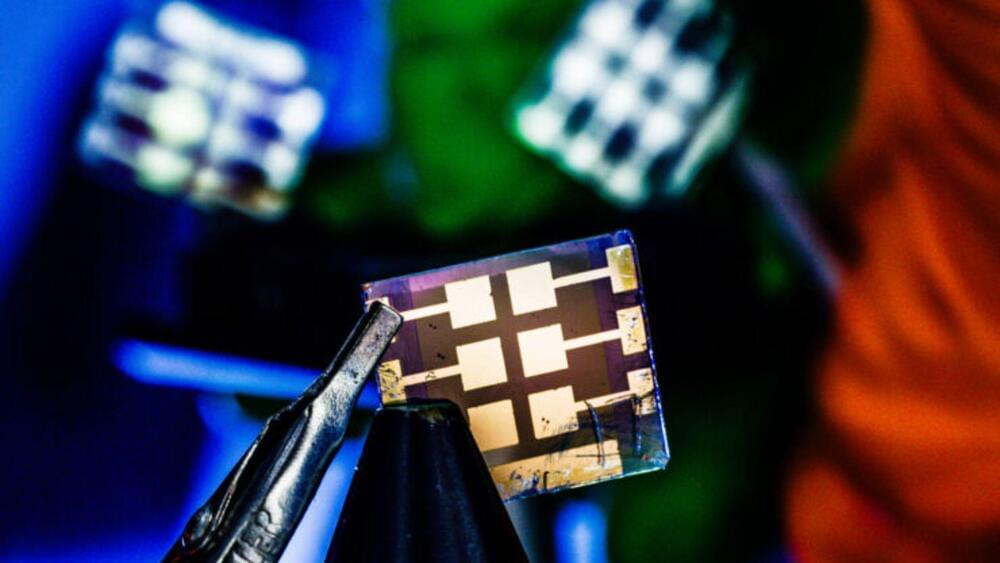

“A crucial question we constantly face is how much we can curve the signal and over what distance,” acknowledges Mittleman. “We have initial estimations, but a more precise understanding is necessary.”

This research, supported by the National Science Foundation and the Air Force Office of Scientific Research, represents a significant step towards a future powered by terahertz communication. By bending the limitations of current technologies, researchers are paving the way for a new era of seamless and high-bandwidth wireless connectivity.

Follow us on X for news, fascinating articles, and discussions with other followers: https://shorturl.at/imHY9

Why is there a world, a cosmos, something, anything instead of absolutely nothing at all? If nothing existed, there would be, well, ‘nothing’ to explain. To have anything existing demands some kind of explanation. Of all the big questions, this is the biggest. Why anything? Why not nothing? What can we learn from the absence of nothing?

Free access to Closer to Truth’s library of 5,000 videos: http://bit.ly/376lkKN

Martin John Rees, Baron Rees of Ludlow is a British cosmologist and astrophysicist. He has been Astronomer Royal since 1995 and Master of Trinity College, Cambridge from 2004 to 2012. He was President of the Royal Society between 2005 and 2010.

Watch more videos on the mystery of existence: https://shorturl.at/dvxAN

This repository contains a re-implementation of the code for the paper Probing the 3D Awareness of Visual Foundation Models (CVPR 2024) which presents an analysis of the 3D awareness of visual foundation models.

Mohamed El Banani, Amit Raj, Kevis-Kokitsi Maninis, Abhishek Kar, Yuanzhen Li, Michael Rubinstein, Deqing Sun, Leonidas Guibas, Justin Johnson, Varun Jampani

If you find this code useful, please consider citing:

Now impacting All Life on Earth.

It’s not the first study on microplastics in Antarctica that researchers from the University of Basel and the Alfred-Wegener Institute (AWI) have conducted. However, data analysis from a spring 2021 expedition reveals that environmental pollution from these tiny plastic particles is a bigger problem in the remote Weddell Sea than was previously known.

The total of 17 seawater samples all indicated higher concentrations of microplastics than in previous studies. “The reason for this is the type of sampling we conducted,” says Clara Leistenschneider, doctoral candidate in the Department of Environmental Sciences at the University of Basel and lead author of the study.

The current study focused on particles measuring between 11 and 500 micrometers in size. The researchers collected them by pumping water into tanks, filtering it, and then analyzing it using infrared spectroscopy. Previous studies in the region had mostly collected microplastic particles out of the ocean using fine nets with a mesh size of around 300 micrometers. Smaller particles would simply pass through these plankton nets.