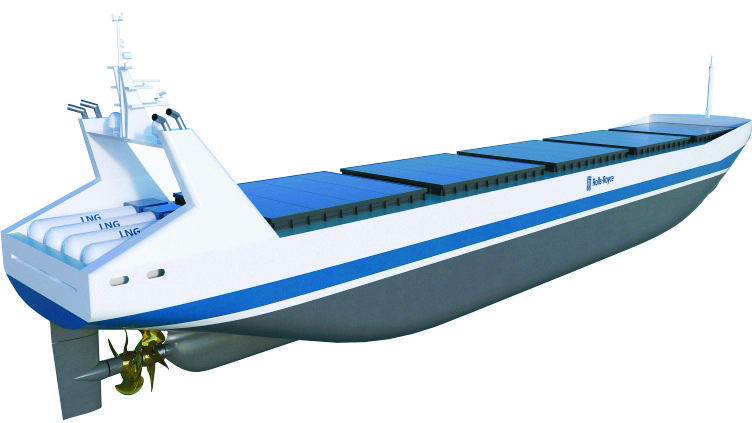

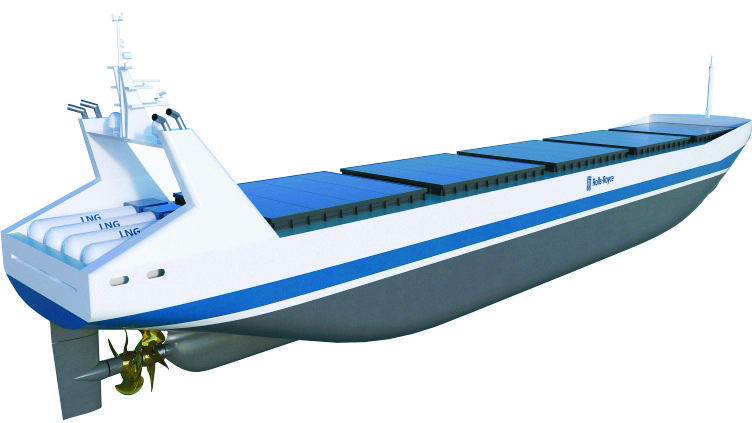

Mining and shipping are industries thus far almost wholly unreconstructed by mobile tech. But IoT is going underground and out to sea.

Here is a machine that uses laser to remove rust and paint from metals. So COOL!

Scientists announced Thursday that they have built a single-celled organism that has just 473 genes — likely close to the minimum number of genes necessary to sustain its life. The development, they say, could eventually lead to new manufacturing methods.

Around 1995, a few top geneticists set out on a quest: to make an organism that had only the genes that were absolutely essential for its survival. A zero-frills life.

It was a heady time.

A professor made a device that can make you invisible.

Click on photo to start video.

Click on photo to start video.

This futuristic floating city will be made out of garbage and house 20,000 residents.

“He is not here; He has risen,” — Matthew 28:6

As billions of Christians around the world are getting ready to celebrate the Easter festival and holiday, we take pause to appreciate the awe inspiring phenomena of resurrection.

In religious and mythological contexts, in both Western and Eastern societies, well known and less common names appear, such as Attis, Dionysus, Ganesha, Krishna, Lemminkainen, Odin, Osiris, Persephone, Quetzalcoatl, and Tammuz, all of whom were reborn again in the spark of the divine.

In the natural world, other names emerge, which are more ancient and less familiar, but equally fascinating, such as Deinococcus radiodurans, Turritopsis nutricula, and Milnesium tardigradum, all of whose abilities to rise from the ashes of death, or turn back time to start life again, are only beginning to be fully appreciated by the scientific world.

In the current era, from an information technology centric angle, proponents of a technological singularity and transhumanism, are placing bets on artificial intelligence, virtual reality, wearable devices, and other non-biological methods to create a future connecting humans to the digital world.

This Silicon Valley, “electronic resurrection” model has caused extensive deliberation, and various factions to form, from those minds that feel we should slow down and understand the deeper implications of a post-biologic state (Elon Musk, Steven Hawking, Bill Gates, the Vatican), to those that are steaming full speed ahead (Ray Kurzweil / Google) betting that humans will shortly be able to “transcend the limitations of biology”.

However, deferring an in-depth Skynet / Matrix discussion for now, is this debate clouding other possibilities that we have forgotten about, or may not have even yet fully considered?

Today, we find ourselves at an interesting point in history where the disciplines of regenerative sciences, evolutionary medicine, and complex systems biology, are converging to give us an understanding of the cycle of life and death, orders of magnitude more complex than only a few years ago.

In addition to the aforementioned species that are capable of biologic reanimation and turning back time, we show no less respect for those who possess other superhuman capabilities, such as magnetoreception, electrosensing, infrared imaging, and ultrasound detection, all of which nature has been optimizing over hundreds of millions of years, and which provide important clues to the untapped possibilities that currently exist in direct biological interfaces with the physical fabric of the universe.

The biologic information processing occurring in related aneural organisms and multicellular colony aggregators, is no less fascinating, and potentially challenges the notion of the brain as the sole repository of long-term encoded information.

Additionally, studies on memory following the destruction all, or significant parts of the brain, in regenerative organisms such as planarians, amphibians, metamorphic insects, and small hibernating mammals, have wide ranging implications for our understanding of consciousness, as well as to the centuries long debate between the materialists and dualists, as to whether we should focus our attention “in here”, or “out there”.

I am not opposed to studying either path, but I feel that we have the potential to learn a lot more about the topic of “out there” in the very near future.

The study of brain death in human beings, and the application of novel tools for neuro-regeneration and neuro-reanimation, for the first time offer us amazing opportunities to start from a clean slate, and answer questions that have long remained unanswered, as well as uncover a knowledge set previously thought unreachable.

Aside from a myriad of applications towards the range of degenerative CNS indications, as well as disorders of consciousness, such work will allow us to open a new chapter related to many other esoteric topics that have baffled the scientific community for years, and fallen into the realm of obscure curiosities.

From the well documented phenomena of terminal lucidity in end stage Alzheimer’s patients, to the mysteries of induced savant syndrome, to more arcane topics, such as the thousands of cases of children who claim to remember previous lives, by studying death, and subsequently the “biotechnological resurrection” of life, we can for the first time peak through the window, and offer a whole new knowledge base related to our place, and our interaction, with the very structure of reality.

We are entering a very exciting era of discovery and exploration.

About the author

Ira S. Pastor is the Chief Executive Officer of Bioquark Inc. (www.bioquark.com), an innovative life sciences company focusing on developing novel biologic solutions for human regeneration, repair, and rejuvenation. He is also on the board of the Reanima Project (www.reanima.tech)