Existential risk from AI is admittedly more speculative than pressing concerns such as its bias, but the basic solution is the same. A robust public discussion is long overdue, says David Krueger

Existential risk from AI is admittedly more speculative than pressing concerns such as its bias, but the basic solution is the same. A robust public discussion is long overdue, says David Krueger

Some of Daniel Schmarchtenberger’s friends say you can be “Schmachtenberged”. It means realising that we are on our way to self-destruction as a civilisation, on a global level. This is a topic often addressed by the American philosopher and strategist, in a world with powerful weapons and technologies and a lack of efficient governance. But, as the catastrophic script has already started to be written, is there still hope? And how do we start reversing the scenario?

After lightning struck a tree in New Port Richey, Florida, a team of scientists from the University of South Florida (USF) discovered that this strike led to the formation of a new phosphorous material in a rock. This is the first time such a material has been found in solid form on Earth and could represent a member of a new mineral group.

“We have never seen this material occur naturally on Earth – minerals similar to it can be found in meteorites and space, but we’ve never seen this exact material anywhere,” said study lead author Matthew Pasek, a geoscientist at USF.

According to the researchers, high-energy events such as lightning can sometimes cause unique chemical reactions which, in this particular case, have led to the formation of a new material that seems to be transitional between space minerals and minerals found on Earth.

We may build incredible AI. But can we contain our cruelty? Oxford professor Nick Bostrom explains.

Up next, Is AI a species-level threat to humanity? With Elon Musk, Michio Kaku, Steven Pinker & more ► https://youtu.be/91TRVubKcEM

Nick Bostrom, a professor at Oxford University and director of the Future of Humanity Institute, discusses the development of machine superintelligence and its potential impact on humanity. Bostrom believes that in this century, we will create the first general intelligence that will be smarter than humans. He sees this as the most important thing humanity will ever do, but it also comes with an enormous responsibility.

Bostrom notes that there are existential risks associated with the transition to the machine intelligence era, such as the possibility of an underlying superintelligence that overrides human civilization with its own value structures. In addition, there is the question of how to ensure that conscious digital minds are treated well. However, if we succeed in ensuring the well-being of artificial intelligence, we could have vastly better tools for dealing with everything from diseases to poverty.

Ultimately, Bostrom believes that the development of machine superintelligence is crucial for a truly great future.

0:00 Smarter than humans.

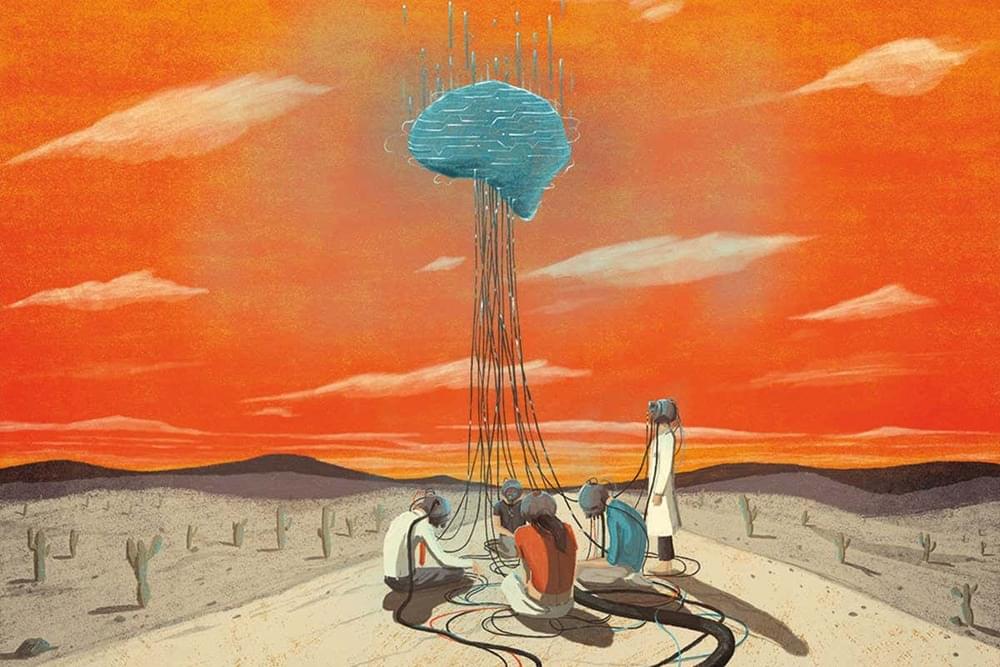

The last few weeks have been abuzz with news and fears (well, largely fears) about the impact chatGPT and other generative technologies might have on the workplace. Goldman Sachs predicted 300 million jobs would be lost, while the likes of Steve Wozniak and Elon Musk asked for AI development to be paused (although pointedly not the development of autonomous driving).

Indeed, OpenAI chief Sam Altman recently declared that he was “a little bit scared”, with the sentiment shared by OpenAI’s chief scientist Ilya Sutskever, who recently said that “at some point it will be quite easy, if one wanted, to cause a great deal of harm”.

As fears mount about the jobs supposedly at risk from generative AI technologies like chatGPT, are these fears likely to prevent people from taking steps to adapt?

And exploration of the Vulnerable World Hypothesis solution to the Fermi Paradox.

And exploration of the possibility of finding fossils of alien origin right here on the surface of the earth.

My Patreon Page:

https://www.patreon.com/johnmichaelgodier.

My Event Horizon Channel:

In 1942 The Manhattan Project was established by the United States as part of a top-secret research and development (R&D) program to produce the first nuclear weapons. The project involved thousands of scientists, engineers, and other personnel who worked on different aspects of the project, including the development of nuclear reactors, the enrichment of uranium, and the design and construction of the bomb. The goal: to develop an atomic bomb before Germany did.

The Manhattan Project set a precedent for large-scale government-funded R&D programs. It also marked the beginning of the nuclear age and ushered in a new era of technological and military competition between the world’s superpowers.

Today we’re entering the age of Artificial Intelligence (AI)—an era arguably just as important, if not more important, than the age of nuclear war. While the last few months might have been the first you’ve heard about it, many in the field would argue we’ve been headed in this direction for at least the last decade, if not longer. For those new to the topic: welcome to the future, you’re late.

Several asteroids are set to dash past Earth in the coming days, according to a list released by NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, close encounters that are almost certain to pass harmlessly and come days after the White House announced new plans to defend the planet against threats from space.

Two asteroids, one bus-sized and the other the size of a house, will make relatively close approaches to Earth on Wednesday, according to NASA’s Asteroid Watch Dashboard.

Three more, all approximately airplane-sized, are also set to whizz past Earth on Thursday, the agency said.

Three plane-sized asteroids—and one the size of a house—are set to pass close by Earth on Wednesday and Thursday, NASA said.

Machine learning has been leveraged to accelerate analysis in nuclear processing facilities and investigations in the field.

Surprise nuclear attacks or threats will soon be a thing of the past. Researchers at the Department of Energy’s Pacific Northwest National Laboratory (PNNL), U.S., have developed new techniques to accelerate the discovery and understanding of nuclear weapons by leveraging machine learning.

One enticing application of these new techniques in national security is to use data analytics and machine learning to monitor several ingredients used to produce nukes.

FallenKingdomReads’ list of five must-read science fiction books for fans of The Matrix.

This dystopian novel is the basis for the classic film Blade Runner, and it explores a world devastated by nuclear war where bounty hunter Rick Deckard must retire six rogue androids.

In this novel, human consciousness is digitized and can be transferred between bodies, leading to an interstellar conspiracy that draws the protagonist Takeshi into a thrilling adventure.