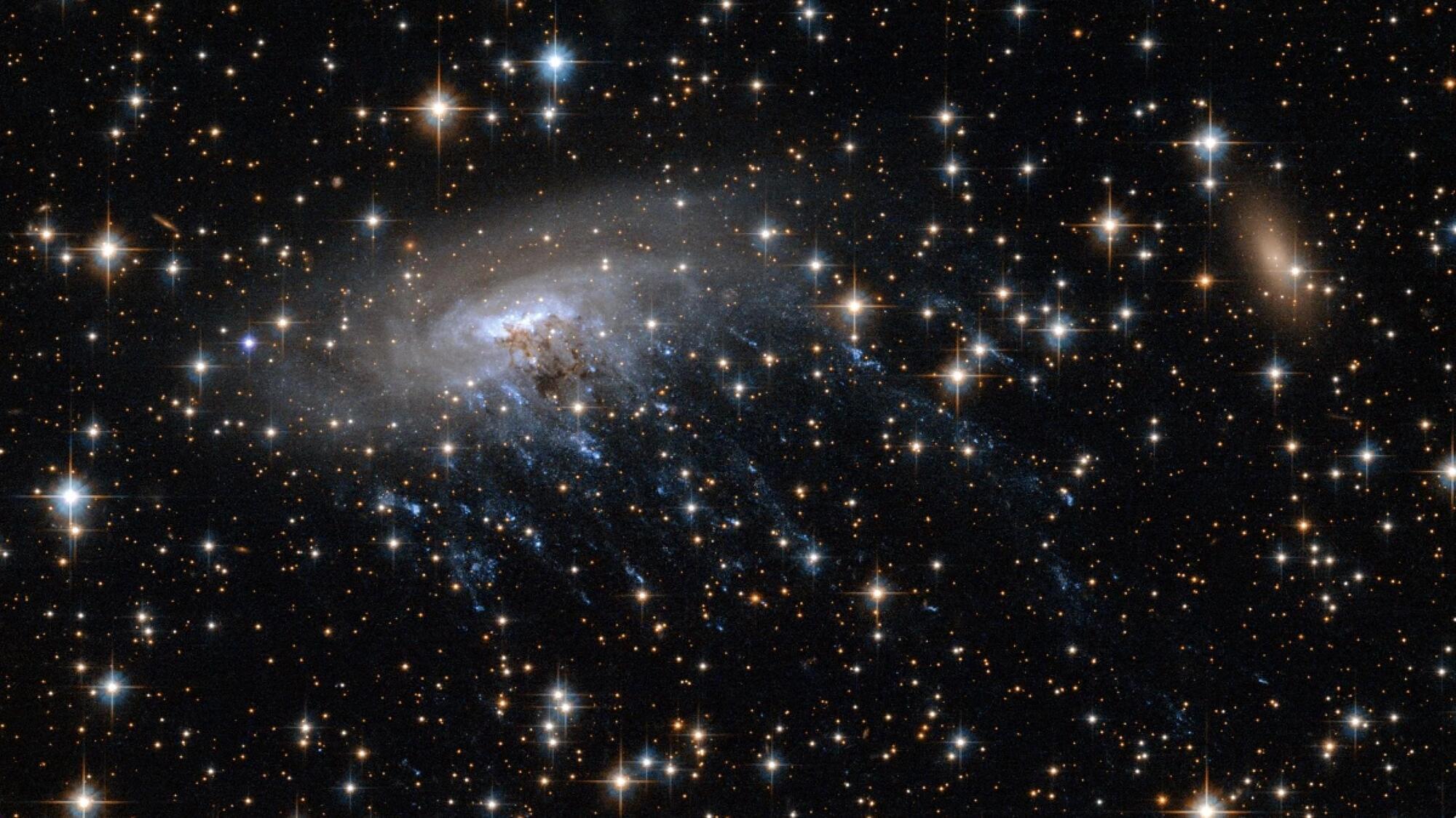

Depending on the temperature and pressure, ice adopts one of 20 different crystalline phases. Researchers can typically tell one ice phase from the other using x rays or neutron beams, but such techniques are impractical for studying ice on distant celestial bodies. Thomas Loerting from the University of Innsbruck in Austria and his colleagues have now shown that infrared spectroscopy can discriminate between two types of high-pressure ice [1]. The results suggest that astronomical observatories in the infrared could probe ice-covered planets or moons, revealing information about their geological evolution and potential habitability.

The ice in your freezer is hexagonal ice, but at lower temperatures, higher pressures, or both, other forms can exist. Ice phases are distinguished by the ordering of oxygen atoms and hydrogen atoms. For example, ice V has oxygens arranged in ring structures, while its hydrogens have random (disordered) positions. This phase, which is stable at pressures of 500 megapascals and temperatures of 253 K, is thought to form in the interior of Jupiter’s moon Ganymede, Saturn’s moon Enceladus, and other icy moons.

In the lab, Loerting’s colleague, Christina Tonauer, created ice V, along with a related, hydrogen-ordered version called ice XIII. The team performed near-infrared spectroscopy on both samples and identified several distinguishing features, including a structure-dependent “shoulder” around 1.6 µm, a wavelength associated with stretching modes. According to the team’s calculations, the features are strong enough that astronomical instruments, such as those on the JWST observatory and the Jupiter-visiting JUICE mission, could potentially observe them on a body like Ganymede. “The detection of high-pressure ice phases at or near the surface could point to internal processes such as tectonic activity, cryovolcanism, or convective transport from deeper layers,” Loerting says.