The U.S. intelligence community (IC) on Thursday rolled out an “ethics guide” and framework for how intelligence agencies can responsibly develop and use artificial intelligence (AI) technologies.

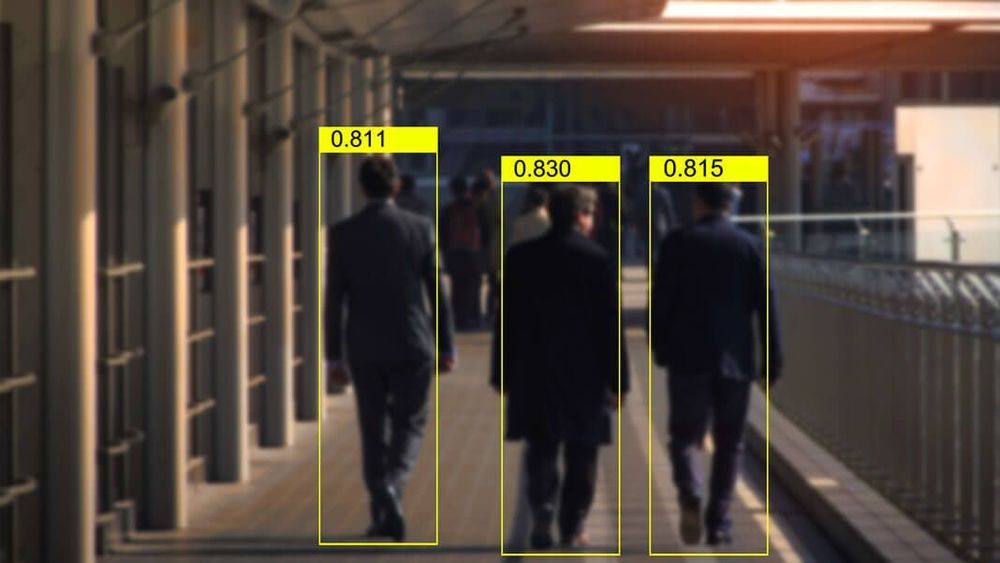

Among the key ethical requirements were shoring up security, respecting human dignity through complying with existing civil rights and privacy laws, rooting out bias to ensure AI use is “objective and equitable,” and ensuring human judgement is incorporated into AI development and use.

The IC wrote in the framework, which digs into the details of the ethics guide, that it was intended to ensure that use of AI technologies matches “the Intelligence Community’s unique mission purposes, authorities, and responsibilities for collecting and using data and AI outputs.”