FEBRUARY 10/2014 LIST OF UPDATES. By Mr. Andres Agostini at The Future of Scientific Management, Today! At http://lnkd.in/bYP2nDC

UPDATE 1-China central bank urges proper management of risk, liquidity

http://www.reuters.com/article/2014/02/08/china-economy-cenb…8720140208

Iran sending warships close to U.S. borders

http://www.politico.com/story/2014/02/iran-warships-us-borders-103288.html

Apple’s Tim Cook on Plans for Cash and Emerging Markets

http://blogs.wsj.com/digits/2014/02/07/apple-still-a-growth-…interview/

World’s first 3D-printed titanium bicycle frame could lead to cheaper, lighter bikes

http://www.gizmag.com/3d-printed-titanium-bicycle-frame/3076…witterfeed

Ignore the Unemployment Rate. The most totemic statistic about the U.S. economy is archaic and misleading

http://online.wsj.com/news/articles/SB1000142405270230349680…ss_economy

Why Problems Are An Entrepreneur’s Best Friend

http://www.forbes.com/sites/janbruce/2014/01/28/why-problems…st-friend/

Gastric surgery increases risk of alcoholism

http://www.independent.co.uk/life-style/health-and-families/…17066.html

Snowden nicked NSA docs with common tool, raising more concern about agency — report

http://news.cnet.com/8301-13578_3-57618608-38/sn…cy-report/

Tribeca and CERN Want To Change Storytelling With A Hackathon

http://www.fastcolabs.com/3026107/tribeca-and-cern-want-to-c…Company%29

3D Printed Hip Implant Allows Teen to Finally Walk

http://3dprint.com/3d-printed-hip-implant-allows-teen-to-finally-walk/

Many Promising Embryonic Stem Cell Therapies Ensnared In Legal Loophole

http://www.popsci.com/article/science/many-promising-embryon…SOC&dom=tw

High Potential for Life Circling Alpha Centauri B, our Nearest Neighbor

High Potential for Life Circling Alpha Centauri B, our Nearest Neighbor

Countervailing motion

http://www.economist.com/news/finance-and-economics/21595937…-are-still

Toyota’s $1 Billion Fine Begs Question: Do We Really Want To Regulate This Way?

http://www.forbes.com/sites/danielfisher/2014/02/08/toyotas-…ium=social

Single-pole magnet emerges in frozen concoction

The 50 Most Powerful Women in Business: Global edition

http://money.cnn.com/gallery/leadership/2014/02/06/global-mo…ign=buffer

How To Win When You Fail

http://www.entrepreneur.com/article/231260

How the speed of technological change can be an opportunity

http://fcw.com/articles/2014/02/05/smith-speed-of-change.aspx

Welcome to the Multiverse

http://discovermagazine.com/2011/oct/18-out-there-welcome-to…vcVIYWGiHd

Quantum Computing: A Primer

What the Singularity Will Mean at the Office

http://blogs.wsj.com/cio/2014/02/06/what-the-singularity-wil…he-office/

Alvin deep-sea sub cleared to start next half-century of service

http://www.gizmag.com/alvin-return/30617/

U.S. Experimented With Nuclear Fracking

http://orwellwasright.co.uk/2014/02/02/u-s-experimented-with-nuclear-fracking/

Terrific: Iranian warships approaching U.S. maritime borders

http://www.caintv.com/breaking-iranian-warships-appr

How To Keep Your Team And Make Your Startup Acquisition Succeed

How To Keep Your Team And Make Your Startup Acquisition Succeed

‘Minority Report’ technology is real and it’s here (and it’s cool)

http://www.chicagobusiness.com/article/20140204/BLOGS11/1402…it-s-cool#

Nanotechnology holds promise for security applications

http://www.securityinfowatch.com/article/11293426/a-look-at-…plications

7 Ways To Be More Productive At Work

http://www.investopedia.com/slide-show/7-ways-productive-work/

The Inevitable Collision Of Technology and Politics

http://www.digitaltonto.com/2014/the-inevitable-collision-of…-politics/

New Journal Article Sheds Light on Past Earth Warming Events

Headlines: New Journal Article Sheds Light on Past Earth Warming Events

Why Steve Ballmer Left Microsoft Better Than He Found It

http://www.cio.com/article/747901/Why_Steve_Ballmer_Left_Mic…e_Found_It

11 Ways to Improve Your IT Team’s Productivity

http://www.cio.com/article/747843/11_Ways_to_Improve_Your_IT_Team_s_Productivity

Experts Warn of Russian Spying, Hackers at Sochi Olympics

http://www.cio.com/article/747846/Experts_Warn_of_Russian_Sp…i_Olympics

How to Get the Job You Want in 2014’s Hot IT Job Market

http://www.cio.com/slideshow/detail/139241/How-to-Get-the-Jo…Job-Market

‘Natural cities’ emerge from location-based social media

http://www.impactlab.net/2014/02/08/natural-cities-emerge-fr…ial-media/

MBAs by the Hour: Disrupting the Consulting Model

http://www.bloomberg.com/video/mbas-by-the-hour-disrupting-t…FIolQ.html

Gmail, Hangouts, and other Google services are back to normal after service outage (update)

http://www.theverge.com/2014/1/24/5342252/gmail-hangouts-and…-right-now

6 Attention-Grabbing Direct Mail Designs

http://www.entrepreneur.com/article/230746

Stanford Re:Think Roundup: Achieving Success in Business and Beyond

http://stanfordbusiness.tumblr.com/post/76140155106/stanford…success-in

A robot in every home: Dyson enters race to provide ‘advanced household androids’ for all

http://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/home-news/a-robot-in-ev…17372.html

Hack a 3D Printer Into a Surprisingly Skilled Air Hockey Robot

http://gizmodo.com/hack-a-3d-printer-into-a-surprisingly-ski…1518317429

LAPD IT Chief: “Israel Has Some Amazing Tech”

http://i-hls.com/2014/02/lapd-chief-israel-amazing-tech/?utm…azing-tech

Stanford scientists put free text-analysis tool on the web

http://engineering.stanford.edu/research-profile/stanford-sc…s-tool-web

3 Ways to Test the Accuracy of Your Predictive Models

http://www.kdnuggets.com/2014/02/3-ways-to-test-accuracy-you…odels.html

Big Chinese Internet Companies Are Competing Head On Against Chinese Banks

http://www.businessinsider.com/chinas-banks-battle-internet-…2014-2

Experiment Is Crowdfunding Science Projects, Just Don’t Ask Them To Find Bigfoot

http://www.forbes.com/sites/hollieslade/2014/02/07/experimen…ium=social

Energy firms’ gas profit margins questioned by minister

http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/business-26112330

How Micro-Location, Geofencing and Indoor Location Are Driving The Retail Revolution

http://www.gislounge.com/opinion-piece-micro-location-geofen…evolution/

Climate change: Weather of Olympian extremes

http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2014/feb/09/leader-…CMP=twt_fd

FDA Panel to Weigh Painkillers’ Cardiac Risk

http://online.wsj.com/news/articles/SB1000142405270230387450…rss_Health

Silicon Valley Isn’t a Meritocracy. And It’s Dangerous to Hero-Worship Entrepreneurs

http://www.wired.com/opinion/2013/11/silicon-valley-isnt-a-m…ople-back/

WIRED Space Photo of the Day

http://www.wired.com/wiredscience/2014/02/wired-space-photo-…34261:full

This Is The Best Free Online Course For Entrepreneurs

http://www.businessinsider.com/best-online-course-for-entrepreneurs-2014-2

The cost of capital is higher for entities that are not audited

http://www.kpmg.com/global/en/topics/value-of-audit/intervie…f1404795=1

New Business Models Need New Approaches to IT

http://cioofthefuture.com/new-business-models-need-new-approaches-to-it/

The 10 Weirdest Things Thieves Steal: 24/7 Wall St.

http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2014/02/09/weird-steal_n_47566…mg00000067

Why Is EnerNOC Funding a Solar Software Startup?

http://www.greentechmedia.com/articles/read/enernoc-invests-…h+Media%29

Yelp And Yahoo Are Reportedly Teaming Up

Does grass-fed beef have any heart-health benefits that other types of beef don’t?

http://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/heart-disease/…Q-20058059

Starwatch: Supernova in Ursa Major

http://www.theguardian.com/science/2014/feb/09/starwatch-sup…CMP=twt_fd

Warren Buffett Made A Bet In 2008 That Has The Potential To Make The Hedge Fund Industry Look Very Bad

http://www.businessinsider.com/warren-buffetts-hedge-fund-bet-2014-2

Victorian fires: emergency continues after at least 20 homes lost — live updates

http://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/feb/10/victorian-fires…CMP=twt_fd

Climate slowdown? Just wait until the wind changes

http://www.newscientist.com/article/dn25015-climate-slowdown…anges.html

NASA is now accepting applications from companies that want to mine the moon

http://www.theverge.com/2014/2/9/5395684/nasa-begins-hunt-fo…n-catalyst

Entering the Era of Private and Semi-Anonymous Apps

Three rules for success: Michael Raynor at TEDxUniversity

QUOTATION(S): “…It reminds us that, in our accelerating, headlong era, the future presses so close upon us that those who ignore it inhabit not the present but the past …” AND “…The future is not a privilege but a perpetual conquest…”

CITATION(S): “…The world has profoundly changed … The challenges and complexity we face in our personal lives and relationships, in our families, in our professional lives, and in our organizations are of a different order of magnitude. In fact, many mark 1989 ─ the year we witnessed the fall of the Berlin Wall ─ as the beginning of the Information Age, the birth of a new reality, a sea change of incredible significance ─ truly a new era ─ Being effective as individuals and organizations is no longer merely an option ─ survival in today’s world requires it. But in order to thrive, innovate, excel, and lead in what Covey calls the new Knowledge Worker Age, we must build on and move beyond effectiveness [long-held assumptions, fallacies and flawed beliefs and faulty conventions]…Accessing the higher levels of human genius and motivation in today’s new reality REQUIRES A SEA CHANGE IN THINKING: a new mind-set, a new skill-set, a new tool-set ─ in short, a whole new habit…”

BOOK(S): The Resilient Enterprise: Overcoming Vulnerability for Competitive Advantage by Yossi Sheffi. ISBN-13: 978–0262693493

Regards,

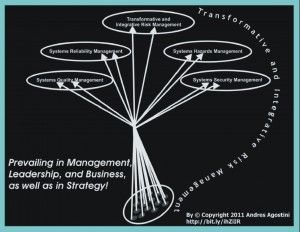

Mr. Andres Agostini

Risk-Management Futurist

and Success Consultant

http://lnkd.in/bYP2nDC