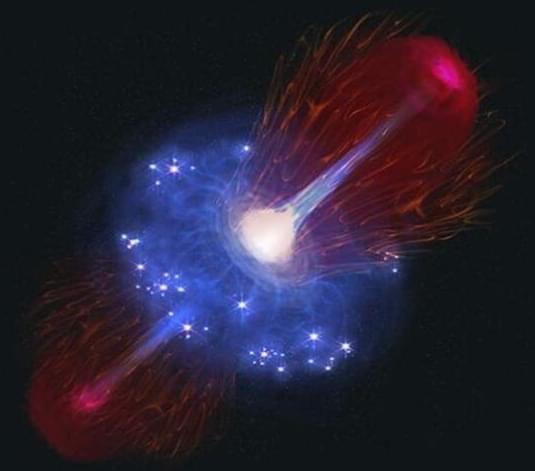

String theory proposes that all particles and forces are made of tiny, vibrating strings, which form the fundamental building blocks of the universe. This framework offers a potential solution to the long-standing paradoxes surrounding black holes, such as their singularities—infinitely tiny points where the laws of physics break down—and the Hawking radiation paradox, which questions the fate of information falling into black holes.

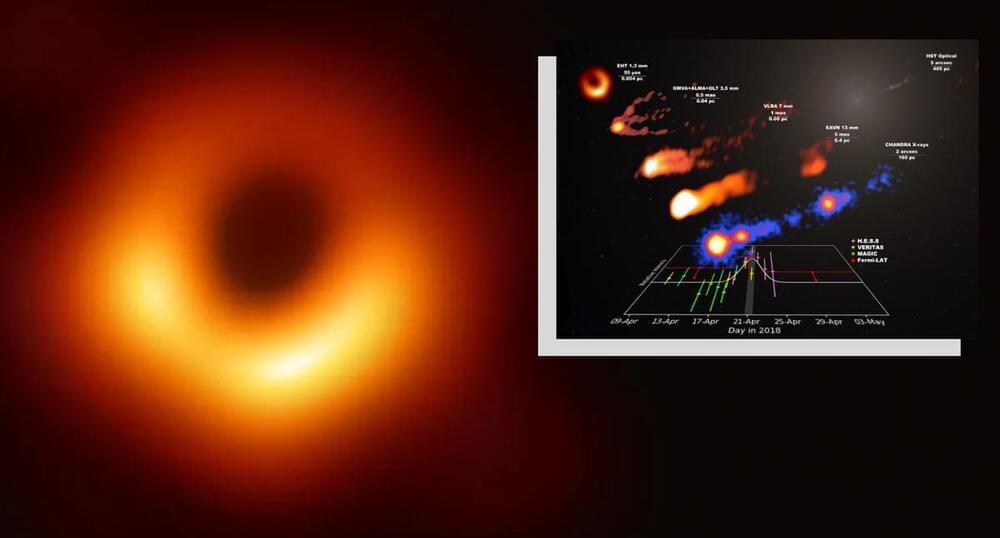

Fuzzballs replace the singularity with an ultra-compressed sphere of strings, likened to a neutron star’s structure but composed of subatomic strings instead of particles. While the theory remains incomplete, its implications are significant, offering an alternative explanation for phenomena previously attributed to black holes.

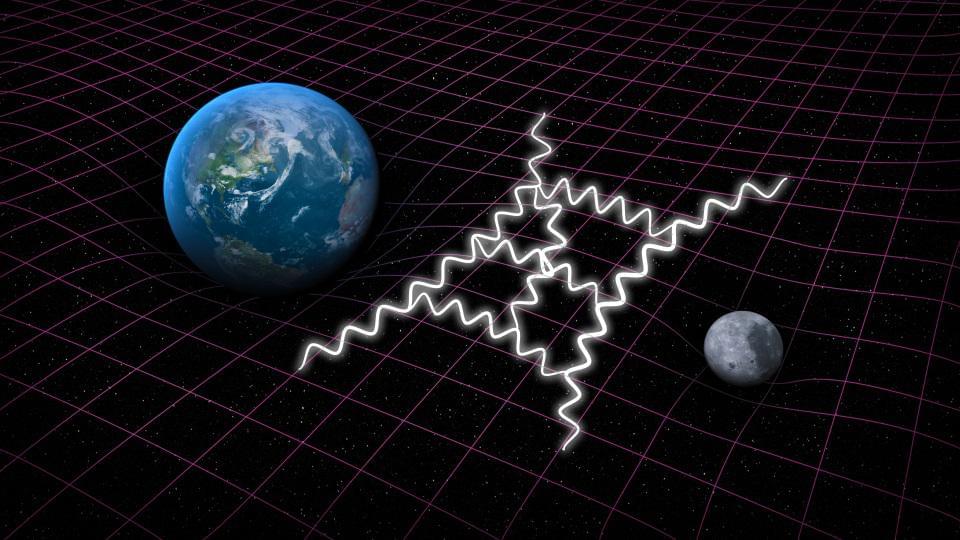

To differentiate between black holes and fuzzballs, researchers are turning to gravitational waves—ripples in spacetime caused by cosmic collisions. When black holes merge, they emit specific gravitational wave signatures that have so far aligned perfectly with Einstein’s general relativity. However, fuzzballs might produce subtle deviations from these patterns, providing a way to confirm their existence.