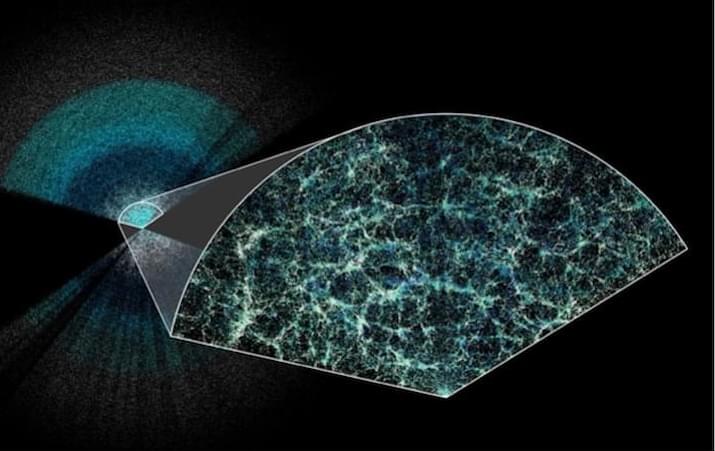

Recent findings from the Dark Energy Spectroscopic Instrument suggest the possibility of new physics that extends beyond the current standard model of cosmology. Using the lab’s new Aurora exascale computing system, the research team conducted high-resolution simulations of the universe’s evoluti

Category: cosmology – Page 55

All but one of Andromeda’s 37 satellite galaxies point toward the Milky Way—something so strange it challenges current cosmology

A recent study published in Nature Astronomy has revealed that the dwarf galaxies orbiting around Andromeda, our neighboring galaxy, are distributed in such an uneven way that it calls into question the most widely accepted cosmological theories. According to the researchers, this asymmetric arrangement is so extreme that it is almost impossible to explain with current models of the universe.

Andromeda, also known as M31, is the spiral galaxy closest to the Milky Way and, like our galaxy, is surrounded by a group of smaller dwarf galaxies that orbit around it. What has surprised scientists is that these dwarf galaxies are not evenly distributed.

Of the 37 observed dwarf galaxies, all but one are located on one side of Andromeda—specifically, the side facing the Milky Way. This uneven arrangement is as if, when throwing a handful of stones around a tree, almost all of them landed on just one side.

Every 4.5 Days, This Black Hole Unleashes Explosive X-Ray Blasts — NASA Finally Explains Why

Astronomers are unraveling the mystery behind Ansky, a black hole system emitting powerful, repeating X-ray bursts called QPEs. These outbursts may result from a small object colliding with a gas disk, sending debris flying at near-light speeds. New Glimpse Into Mysterious X-Ray Outbursts For t

Are wormholes possible?

Lex Fridman Podcast full episode: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=A6m4iJIw_84

Thank you for listening ❤ Check out our sponsors: https://lexfridman.com/sponsors/cv8828-sb.

See below for guest bio, links, and to give feedback, submit questions, contact Lex, etc.

*GUEST BIO:*

Janna Levin is a theoretical physicist and cosmologist specializing in black holes, cosmology of extra dimensions, topology of the universe, and gravitational waves.

*CONTACT LEX:*

*Feedback* — give feedback to Lex: https://lexfridman.com/survey.

*AMA* — submit questions, videos or call-in: https://lexfridman.com/ama.

*Hiring* — join our team: https://lexfridman.com/hiring.

*Other* — other ways to get in touch: https://lexfridman.com/contact.

*EPISODE LINKS:*

Janna’s X: https://twitter.com/JannaLevin.

Janna’s Website: https://jannalevin.com.

Janna’s Instagram: https://instagram.com/jannalevin.

Janna’s Substack: https://substack.com/@jannalevin.

Black Hole Survival Guide (book): https://amzn.to/3YkJzT5

Black Hole Blues (book): https://amzn.to/42Nw7IE

How the Universe Got Its Spots (book): https://amzn.to/4m5De8k.

A Madman Dreams of Turing Machines (book): https://amzn.to/3GGakvd.

*SPONSORS:*

To support this podcast, check out our sponsors & get discounts:

*Brain.fm:* Music for focus.

Go to https://lexfridman.com/s/brainfm-cv8828-sb.

*BetterHelp:* Online therapy and counseling.

Go to https://lexfridman.com/s/betterhelp-cv8828-sb.

*NetSuite:* Business management software.

Go to https://lexfridman.com/s/netsuite-cv8828-sb.

*Shopify:* Sell stuff online.

Go to https://lexfridman.com/s/shopify-cv8828-sb.

*AG1:* All-in-one daily nutrition drink.

Go to https://lexfridman.com/s/ag1-cv8828-sb.

*PODCAST LINKS:*

Are Many Worlds & Pilot Wave THE SAME Theory?

PBS Member Stations rely on viewers like you. To support your local station, go to: http://to.pbs.org/DonateSPACE

Sign Up on Patreon to get access to the Space Time Discord!

/ pbsspacetime.

It’s hard to interpret the strange results of quantum mechanics, though many have tried. Interpretations range from the outlandish—like the multiple universes of Many Worlds, to the almost mundane, like the very mechanical Pilot Wave Theory. But perhaps we’re converging on an answer, because some are arguing that these two interpretations are really the same thing.

Check out the Space Time Merch Store.

https://www.pbsspacetime.com/shop.

Sign up for the mailing list to get episode notifications and hear special announcements!

https://mailchi.mp/1a6eb8f2717d/space… the Entire Space Time Library Here: https://search.pbsspacetime.com/ Hosted by Matt O’Dowd Written by Taha Dawoodbhoy & Matt O’Dowd Post Production by Leonardo Scholzer, Yago Ballarini & Stephanie Faria Directed by Andrew Kornhaber Associate Producer: Bahar Gholipour Executive Producers: Eric Brown & Andrew Kornhaber Executive in Charge for PBS: Maribel Lopez Director of Programming for PBS: Gabrielle Ewing Assistant Director of Programming for PBS: John Campbell Spacetime is produced by Kornhaber Brown for PBS Digital Studios. This program is produced by Kornhaber Brown, which is solely responsible for its content. © 2023 PBS. All rights reserved. End Credits Music by J.R.S. Schattenberg: / multidroideka Space Time Was Made Possible In Part By: Big Bang Sponsors Bryce Fort Peter Barrett David Neumann Sean Maddox Alexander Tamas Morgan Hough Juan Benet Vinnie Falco Fabrice Eap Mark Rosenthal Quasar Sponsors Glenn Sugden Alex Kern Ethan Cohen Stephen Wilcox Mark Heising Hypernova Sponsors Stephen Spidle Chris Webb Ivari Tölp Zachry Wilson Kenneth See Gregory Forfa drollere Bradley Voorhees Scott Gorlick Paul Stehr-Green Ben Delo Scott Gray Антон Кочков Robert Ilardi John R. Slavik Donal Botkin Edmund Fokschaner chuck zegar Jordan Young Daniel Muzquiz Gamma Ray Burst Sponsors Lori Ferris James Sadler Dennis Van Hoof Koen Wilde Nicolas Katsantonis Piotr Sarnicki Massimiliano Pala Thomas Nielson Joe Pavlovic Ryan McGaughy Justin Lloyd Chuck Lukaszewski Cole B Combs Andrea Galvagni Jerry Thomas Nikhil Sharma Ryan Moser John Anderson David Giltinan Scott Hannum Bradley Ulis Craig Falls Kane Holbrook Ross Story teng guo Mason Dillon Matt Langford Harsh Khandhadia Thomas Tarler Susan Albee Frank Walker Matt Quinn Michael Lev Terje Vold James Trimmier Jeremy Soller Paul Wood Joe Moreira Kent Durham Ramon Nogueira Ellis Hall John H. Austin, Jr. Diana S Poljar Faraz Khan Almog Cohen Daniel Jennings Russ Creech Jeremy Reed David Johnston Michael Barton Isaac Suttell Oliver Flanagan Bleys Goodson Mark Delagasse Mark Daniel Cohen Shane Calimlim Eric Kiebler Craig Stonaha Frederic Simon John Robinson Jim Hudson Alex Gan David Barnholdt David Neal John Funai Bradley Jenkins Vlad Shipulin Cody Brumfield Thomas Dougherty King Zeckendorff Dan Warren Joseph Salomone Patrick Sutton Dean Faulk.

Search the Entire Space Time Library Here: https://search.pbsspacetime.com/

How nothing could destroy the universe

The concept of nothing once sparked a 1000-year-long war, today it might explain dark energy and nothingness even has the potential to destroy the universe, explains physicist Antonio Padilla

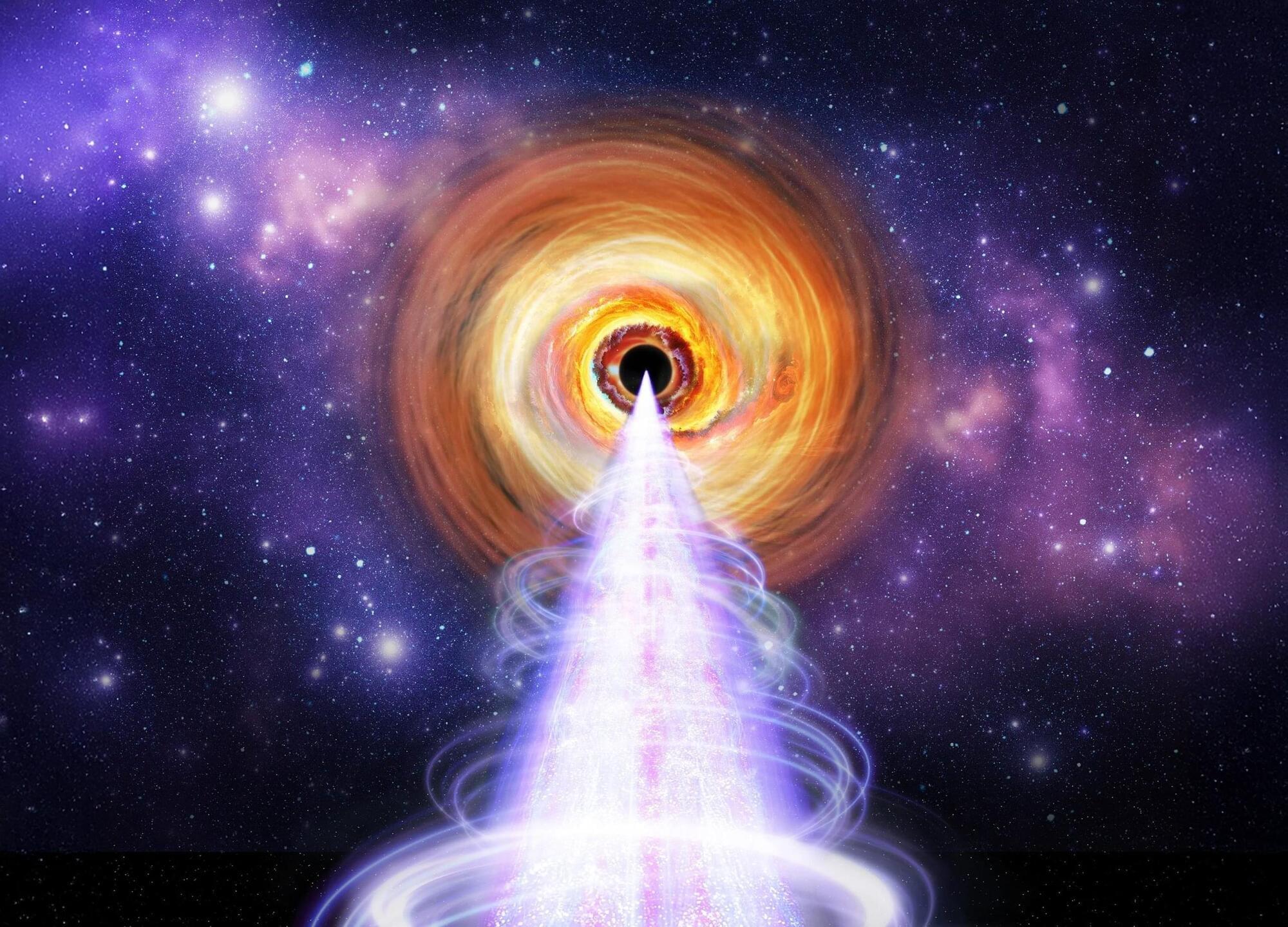

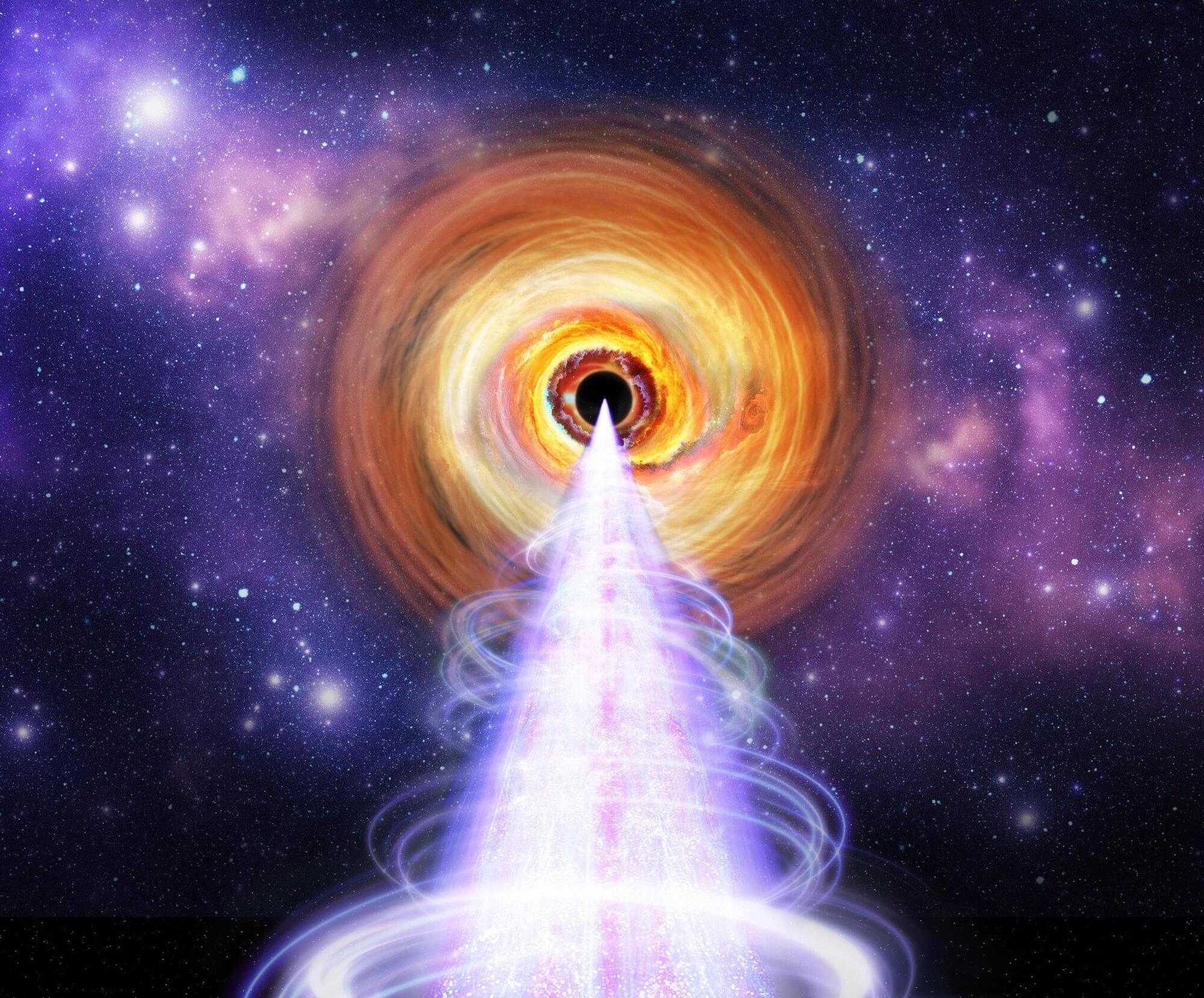

NASA’s IXPE reveals X-ray-generating particles in black hole jets

The blazar BL Lacertae, a supermassive black hole surrounded by a bright disk and jets oriented toward Earth, provided scientists with a unique opportunity to answer a longstanding question: How are X-rays generated in extreme environments like this?

NASA’s IXPE (Imaging X-ray Polarimetry Explorer) collaborated with radio and optical telescopes to find answers. The results, available on the arXiv preprint server and set to be published in the journal Astrophysical Journal Letters, show that interactions between fast-moving electrons and particles of light, called photons, must lead to this X-ray emission.

Scientists had two competing possible explanations for the X-rays, one involving protons and one involving electrons. Each of these mechanisms would have a different signature in the polarization of X-ray light. Polarization is a property of light that describes the average direction of the electromagnetic waves that make up light.