Three physicists won a $3 million Breakthrough prize for proving there is no fifth force (that we know of). And it all started with a series of table-top experiments using cheap equipment.

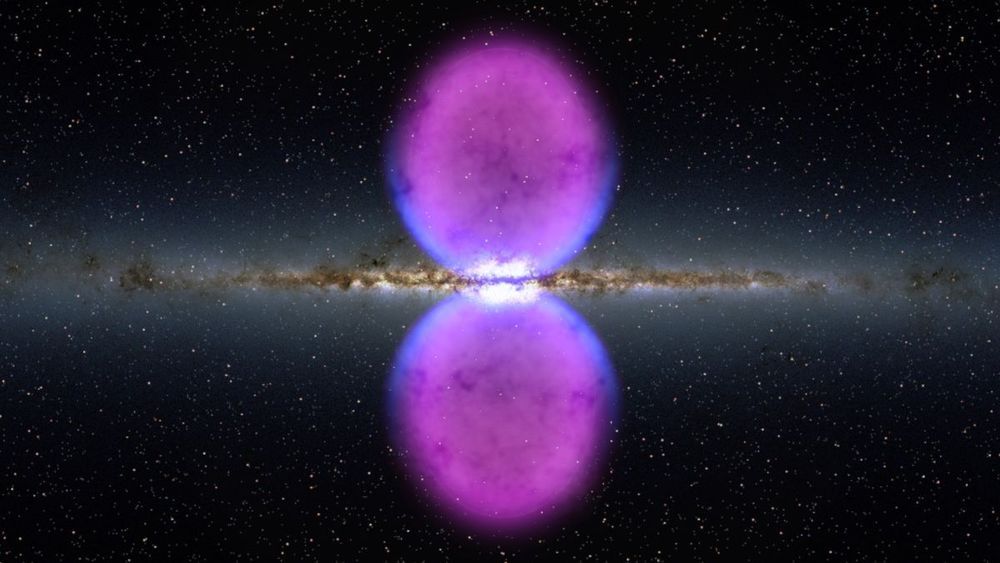

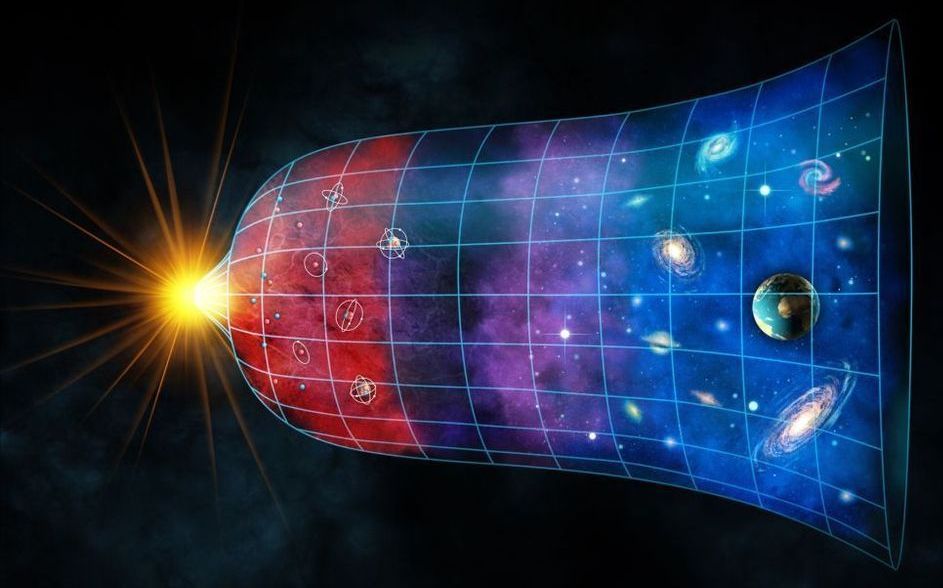

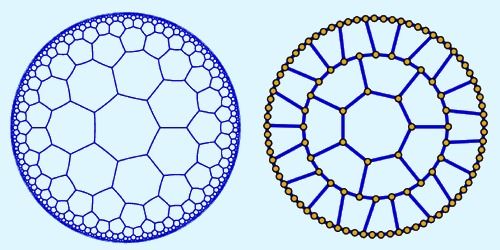

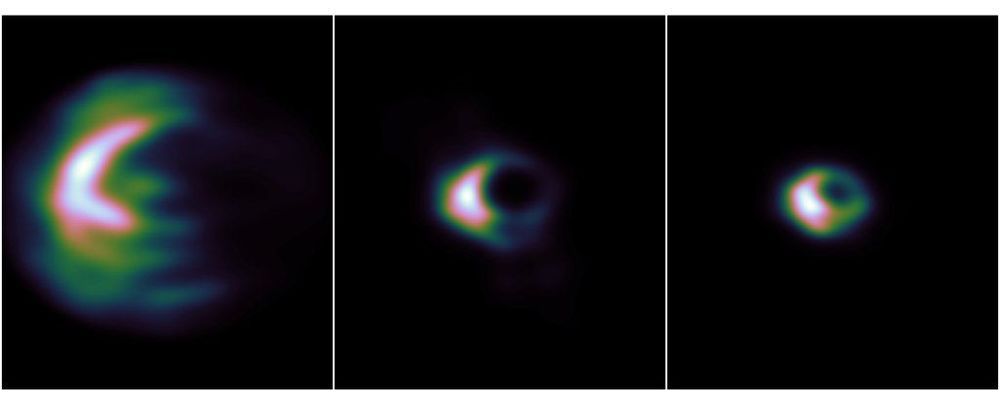

Eric Adelberger, Jens Gundlach and Blayne Heckel together lead the “Eöt-Wash Group,” which is devoted to precise tests of physical laws. They take their name from the early-1900s physicist Loránd Eötvös and the University of Washington, where they work. These Eöt-Wash researchers got their start in the mid-1980s, using a device known as a “torsion balance” to disprove claims of an undiscovered fifth force in physics. Since then, they’ve used more elaborate versions of the same device to test the true strength of gravity, detect the tug of dark matter in the Milky Way and search for theoretical physical effects like extra dimensions and “axion wind.”