A BLACK HOLE breakthrough has been made after experts spotted what is being dubbed as a “missing link” in understanding the universe.

Have you ever experimented with food dye? It can make cooking a lot more fun, and provides a great example of how two fluids can mix together well—or not much at all.

Add a small droplet in water and you might see it slowly dissolve in the larger liquid. Add a few more drops and perhaps you’ll see a wave of color spread, the colored droplets spreading and breaking apart to diffuse more thoroughly. Add a spoon and begin stirring quickly, and you’ll probably find that the water fully changes color, as desired.

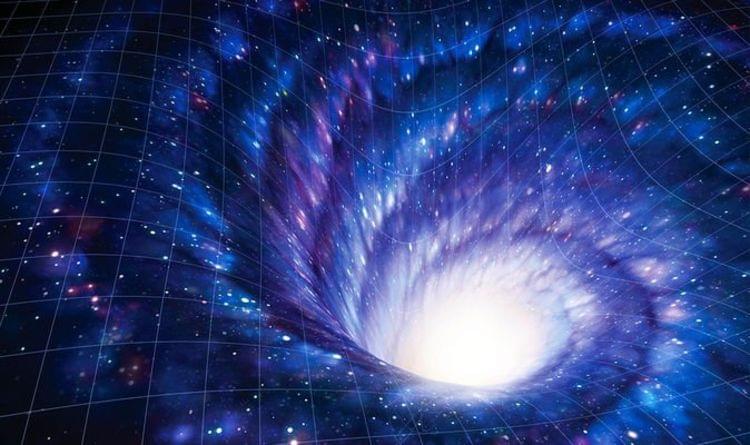

Researchers at the USC Viterbi School of Engineering, led by Ivan Bermejo-Moreno, assistant professor of aerospace and mechanical engineering, studied a similar phenomenon with gases at high speeds, with an eye toward more efficient mixing to support supersonic scramjet engines. In the study, published in Physics of Fluids, USC Viterbi Ph.D. Jonas Buchmeier, along with Xiangyu Gao (USC Viterbi Ph.D. ‘20) and former visiting M.Sc. student Alexander Bußmann (Technical University Munich), developed a novel tracking method that zoomed in on the fundamentals of how mixing happens. The study helps understand, for example, how injected fuel interacts with the surrounding oxidizers (air) in the engine to make it operate optimally, or how interstellar gases mix after a supernova explosion to form new stars. The method focuses on the geometric and physical properties of the turbulent swirling motions of gases and how they change shape over time as they mix.

Learn More about Brilliant: https://brilliant.org/SpaceTime/

Take the PBS Digital Studios audience survey: https://to.pbs.org/2021survey.

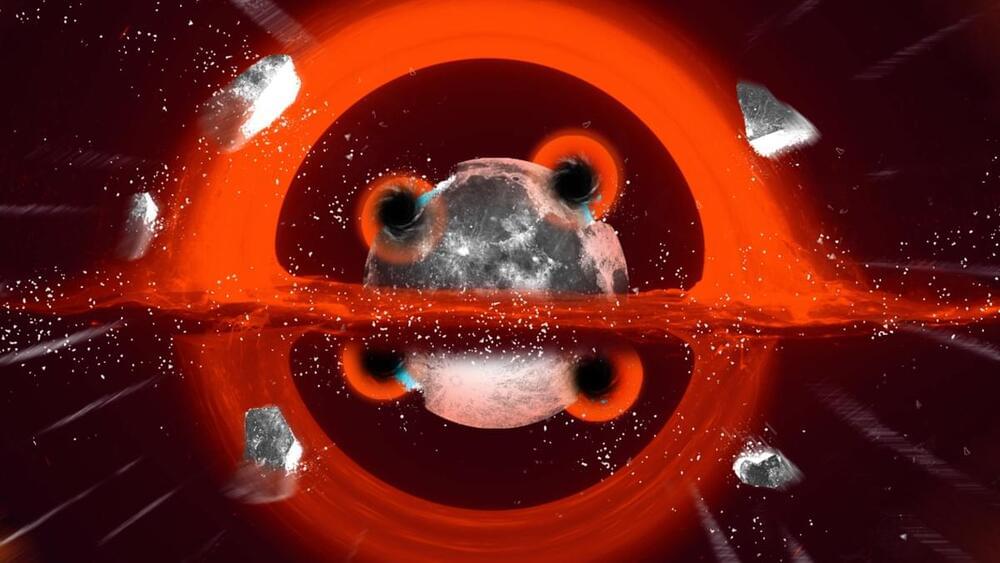

Black holes are a paradox. They are paradoxical because they simultaneously must exist but can’t, and so they break physics as we know it. Many physicists will tell you that the best way to fix broken physics is with string. String theory, in fact. And in the black holes of string theory — fuzzballs — are perhaps even weirder than the regular type.

Sign Up on Patreon to get access to the Space Time Discord!

https://www.patreon.com/pbsspacetime.

Check out the Space Time Merch Store.

https://www.pbsspacetime.com/shop.

Sign up for the mailing list to get episode notifications and hear special announcements!

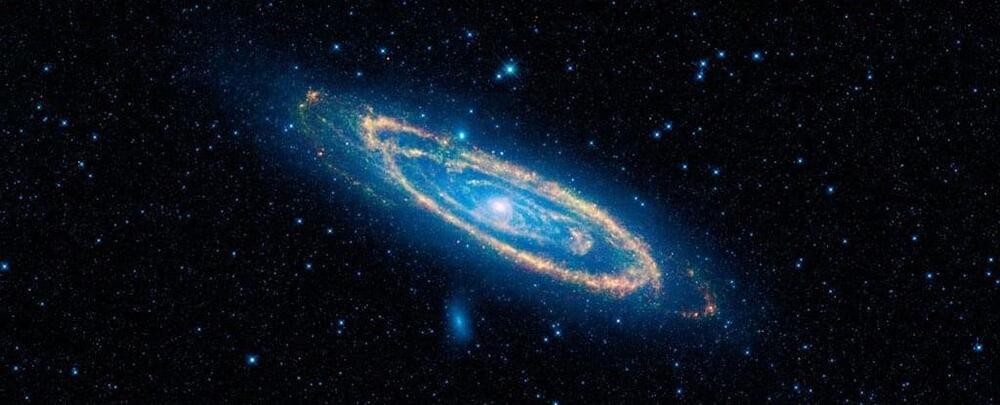

There’s a mysteriously shaped cluster of stars at the center of the Andromeda Galaxy, around 2.5 million light-years away and neighbor to the Milky Way. It’s been causing astronomers to furrow their brows and stroke their chins for decades at this point.

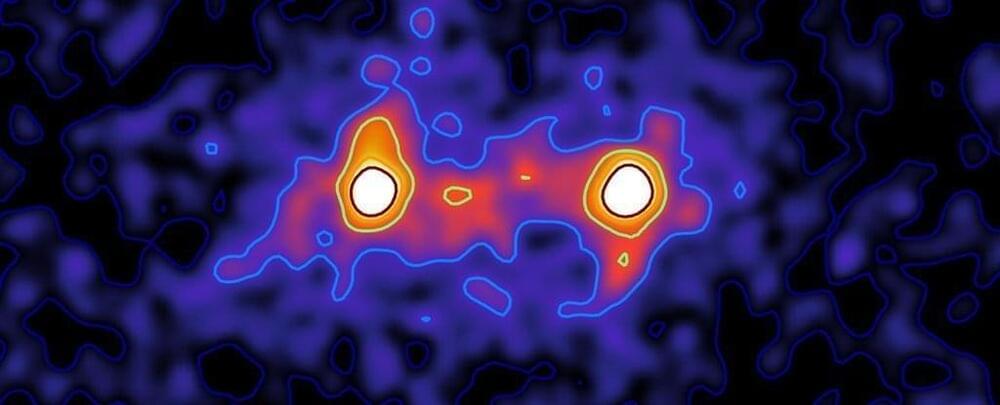

However, new research into how galaxies – and the supermassive black holes at their centers – can collide together may offer an explanation for this cluster. It seems that it might be caused by a gravitational ‘kick’, something similar to the recoil of a shotgun but on a cosmic scale.

This latest study suggests the kick would be powerful enough to create an elongated mass of millions of stars – technically known as an eccentric nuclear disk – instead of the sort of symmetric star cluster that would typically be in the center of a galaxy like Andromeda.

The new theory contradicts earlier predictions that these ‘shortcuts’ would instantly collapse.

Wormholes, or portals between black holes, may be stable after all, a wild new theory suggests.

The findings contradict earlier predictions that these hypothetical shortcuts through space-time would instantly collapse.

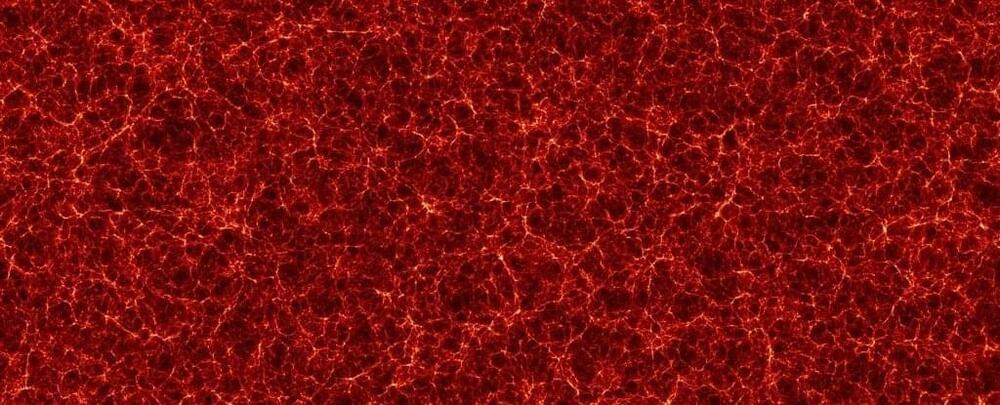

Today, the greatest mysteries facing astronomers and cosmologists are the roles gravitational attraction and cosmic expansion play in the evolution of the Universe.

To resolve these mysteries, astronomers and cosmologists are taking a two-pronged approach. These consist of directly observing the cosmos to observe these forces at work while attempting to find theoretical resolutions for observed behaviors – such as dark matter and dark energy.

In between these two approaches, scientists model cosmic evolution with computer simulations to see if observations align with theoretical predictions. The latest of which is AbacusSummit, a simulation suite created by the Flatiron Institute’s Center for Computational Astrophysics (CCA) and the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics (CfA).

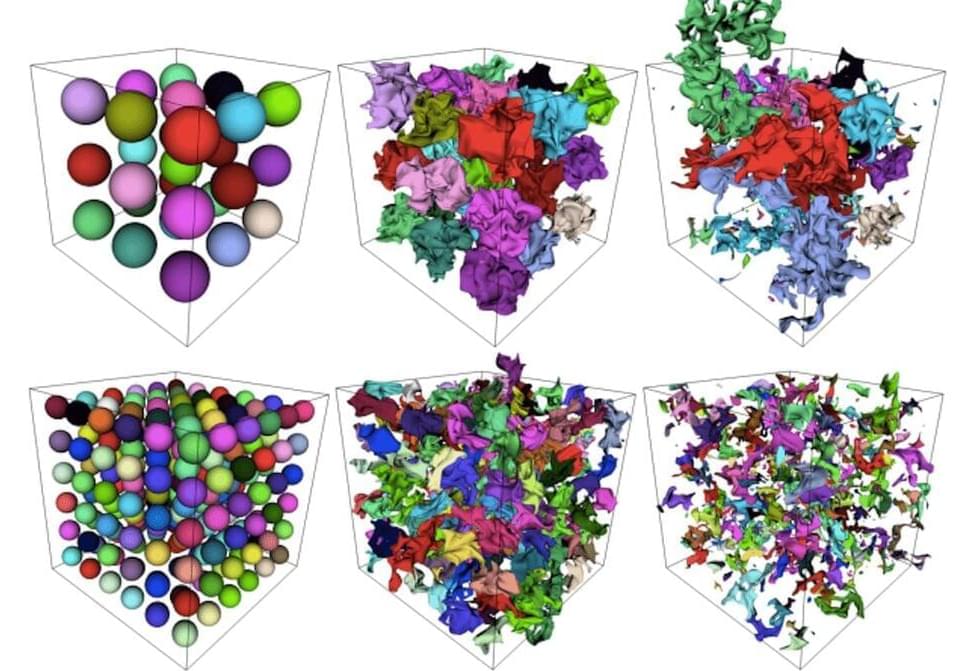

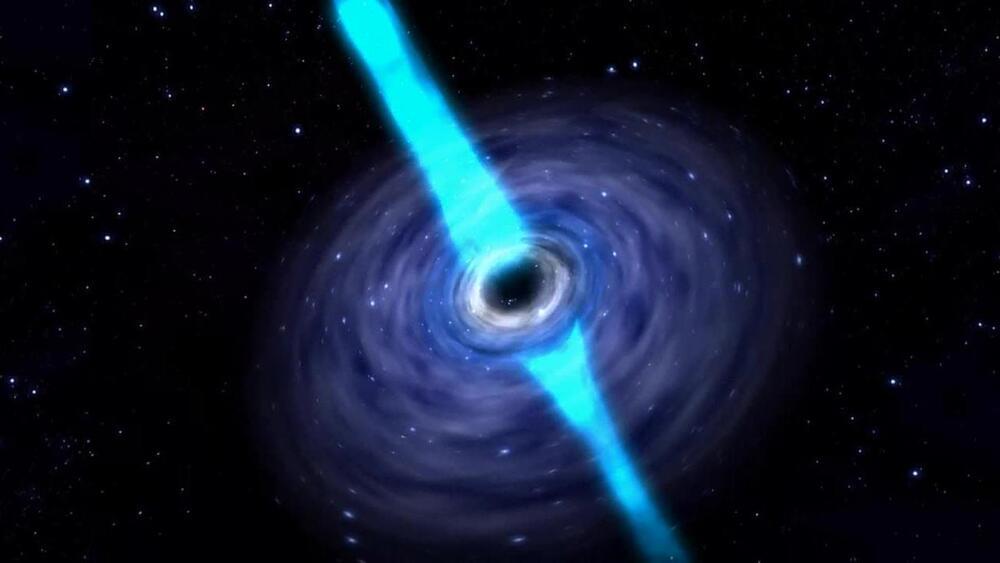

How are chemical elements produced in our Universe? Where do heavy elements like gold and uranium come from? Using computer simulations, a research team from the GSI Helmholtzzentrum für Schwerionenforschung in Darmstadt, together with colleagues from Belgium and Japan, shows that the synthesis of heavy elements is typical for certain black holes with orbiting matter accumulations, so-called accretion disks. The predicted abundance of the formed elements provides insight into which heavy elements need to be studied in future laboratories — such as the Facility for Antiproton and Ion Research (FAIR), which is currently under construction — to unravel the origin of heavy elements. The results are published in the journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

All heavy elements on Earth today were formed under extreme conditions in astrophysical environments: inside stars, in stellar explosions, and during the collision of neutron stars. Researchers are intrigued with the question in which of these astrophysical events the appropriate conditions for the formation of the heaviest elements, such as gold or uranium, exist. The spectacular first observation of gravitational waves and electromagnetic radiation originating from a neutron star merger in 2017 suggested that many heavy elements can be produced and released in these cosmic collisions. However, the question remains open as to when and why the material is ejected and whether there may be other scenarios in which heavy elements can be produced.

Promising candidates for heavy element production are black holes orbited by an accretion disk of dense and hot matter. Such a system is formed both after the merger of two massive neutron stars and during a so-called collapsar, the collapse and subsequent explosion of a rotating star. The internal composition of such accretion disks has so far not been well understood, particularly with respect to the conditions under which an excess of neutrons forms. A high number of neutrons is a basic requirement for the synthesis of heavy elements, as it enables the rapid neutron-capture process or r-process. Nearly massless neutrinos play a key role in this process, as they enable conversion between protons and neutrons.

There’s a lot we still don’t know about dark matter – that mysterious, invisible mass that could make up as much as 85 percent of everything around us – but a new paper outlines a rather unusual hypothesis about the very creation of the stuff.

In short: dark matter creates dark matter. The idea is that at some point in the early stages of the Universe, dark matter particles were able to create more dark matter particles out of particles of regular matter, which would go some way to explaining why there’s now so much of the stuff about.

The new research builds on earlier proposals of a ‘thermal bath’, where regular matter in the form of plasma produced the first bits of dark matter – initial particles which could then have had the power to transform heat bath particles into more dark matter.