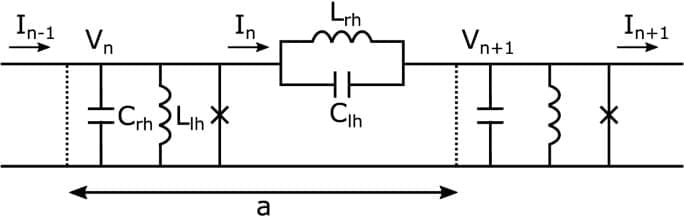

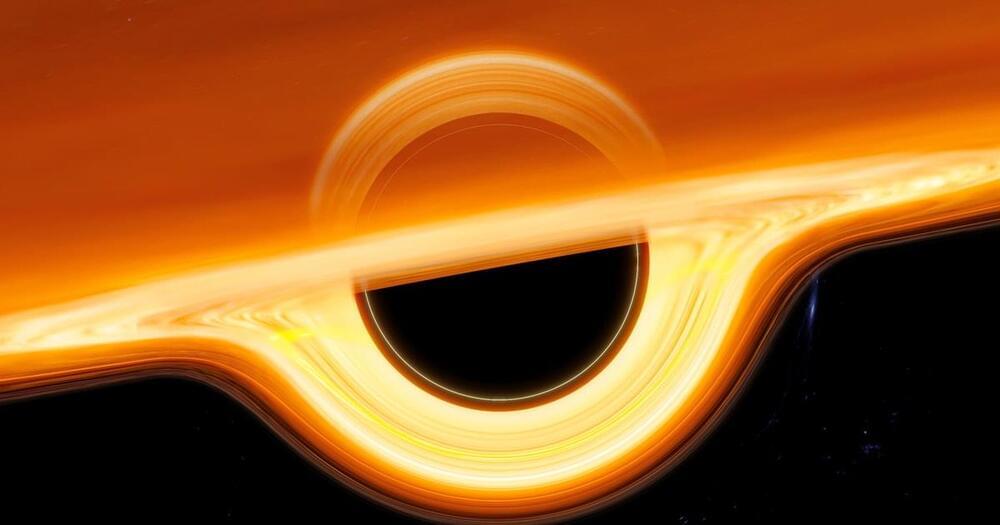

A black hole laser in analogues of gravity amplifies Hawking radiation, which is unlikely to be measured in real black holes, and makes it observable. There have been proposals to realize such black hole lasers in various systems. However, no progress has been made in electric circuits for a long time, despite their many advantages such as high-precision electromagnetic wave detection. Here we propose a black hole laser in Josephson transmission lines incorporating metamaterial elements capable of producing Hawking-pair propagation modes and a Kerr nonlinearity due to the Josephson nonlinear inductance. A single dark soliton obeying the nonlinear Schrödinger equation produces a black hole-white hole horizon pair that acts as a laser cavity through a change in the refractive index due to the Kerr effect.