Issac Arthur play list.

SFIA looks at uses for black holes ranging from spaceships to artificial worlds to escaping the Heat Death of the Universe.

Issac Arthur play list.

SFIA looks at uses for black holes ranging from spaceships to artificial worlds to escaping the Heat Death of the Universe.

There is a lot of culture and philosophy built into the Big Bang theory as we understand it.

Astronomers have recently found the nearest known black hole to our solar system. According to scientists, the black hole is 1,570 lightyears away and ten times larger than our sun.

Known as Gaia BH1, the research was led by Harvard Society Fellow astrophysicist Kareem El-Badry, with the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics (CfA) and the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy (MPIA).

In addition, El-Badry worked with researchers from CfA, MPIA, Caltech, UC Berkeley, the Flatiron Institute’s Center for Computational Astrophysics (CCA), the Weizmann Institute of Science, the Observatoire de Paris, MIT’s Kavli Institute for Astrophysics and Space Research, and other universities.

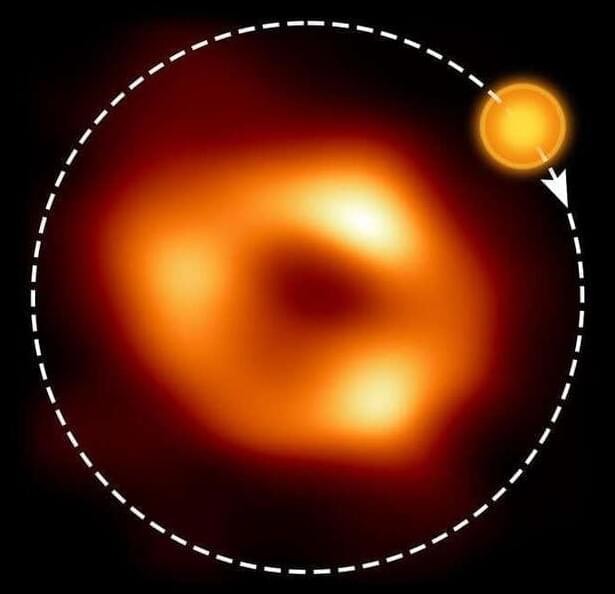

This bubble takes just about an hour to whip around a black hole.

This bubble that circles the event horizon of Sgr A takes just 70 minutes to whip around the black hole. It was observed by the Event Horizon Telescope.

Sailing on light pressure to Near Earth Asteroid (NEA) 2020 GE NEA Scout will be the first mission to use solar light as propulsion to reach a destination in space. It will be launched to the moon by NASA’s Artemis I Space Launch System rocket and sail from there to the asteroid. Learn about this exciting mission directly from Dr. Les Johnson, the Principal Investigator of the light sail.

Worm-hole generators by the pound mass: https://greengregs.com/

For gardening in your Lunar habitat Galactic Gregs has teamed up with True Leaf Market to bring you a great selection of seed for your planting. Check it out: http://www.pntrac.com/t/TUJGRklGSkJGTU1IS0hCRkpIRk1K

Awesome deals for long term food supplies for those long missions to deep space (or prepping in case your spaceship crashes: See the Special Deals at My Patriot Supply: www.PrepWithGreg.com.

Get a Wonderful Person Tee: https://teespring.com/stores/whatdamath.

More cool designs are on Amazon: https://amzn.to/3wDGy2i.

Alternatively, PayPal donations can be sent here: http://paypal.me/whatdamath.

Hello and welcome! My name is Anton and in this video, we will talk about.

Links:

https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.1060182

https://arxiv.org/pdf/1609.01639.pdf.

https://www.nsf.gov/news/mmg/mmg_disp.jsp?med_id=59577&from=

https://www.rle.mit.edu/cua_pub/ketterle_group/Projects_2001…Vortex.htm.

https://dx.doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.129.061302

ISS experiments: https://youtu.be/UEEccJLYVXM

Another similar finding: https://youtu.be/FsTbMfQP7b0

#quantumphysics #blackhole #vortex.

Support this channel on Patreon to help me make this a full time job:

https://www.patreon.com/whatdamath.

Bitcoin/Ethereum to spare? Donate them here to help this channel grow!

bc1qnkl3nk0zt7w0xzrgur9pnkcduj7a3xxllcn7d4

or ETH: 0x60f088B10b03115405d313f964BeA93eF0Bd3DbF

Space Engine is available for free here: http://spaceengine.org.

Enjoy and please subscribe.

Twitter: https://twitter.com/WhatDaMath.