The MICROSCOPE satellite experiment has tested the equivalence principle with an unprecedented level of precision.

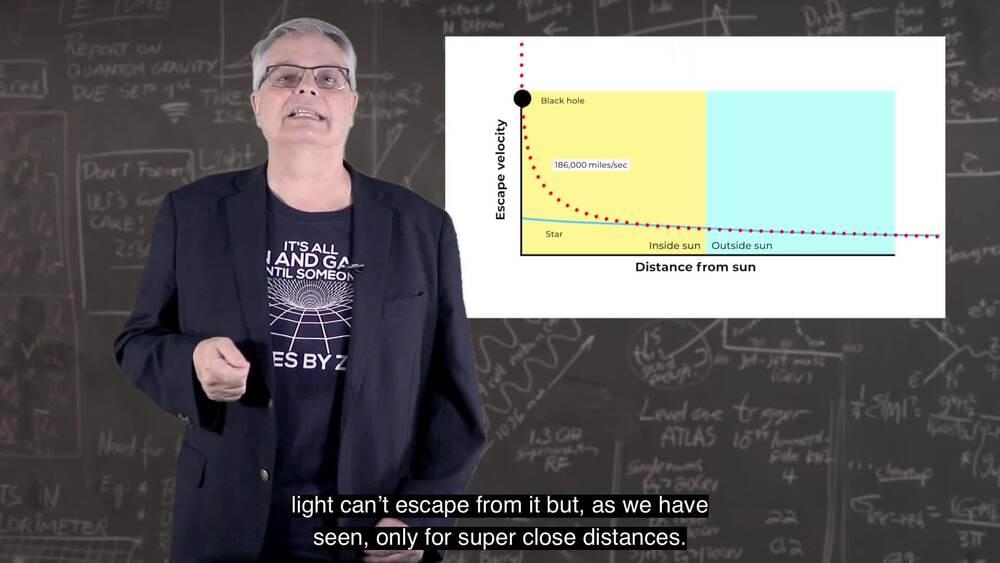

At an early age, we have all been taught one of the most counterintuitive facts about the physical world: two objects of unequal mass dropped in a vacuum will reach the ground simultaneously. Galileo allegedly tested this equivalence principle from the top of the Leaning Tower of Pisa in Italy, and so did the astronaut David Scott by dropping a hammer and a falcon feather at the surface of the Moon in 1971. And yet, we may find these observations disconcerting, as common sense would tell us that a heavier object should fall faster than a lighter one. But gravity is a peculiar interaction. To understand this force—and what it might tell us about other mysteries, such as dark matter and dark energy—we need to test it with ever-increasing precision. The new results by the space-borne MICROSCOPE mission have done just this.