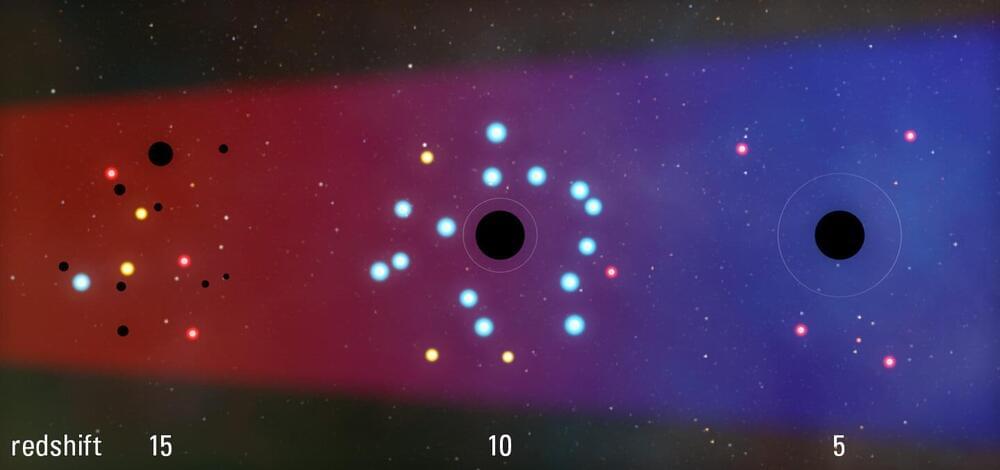

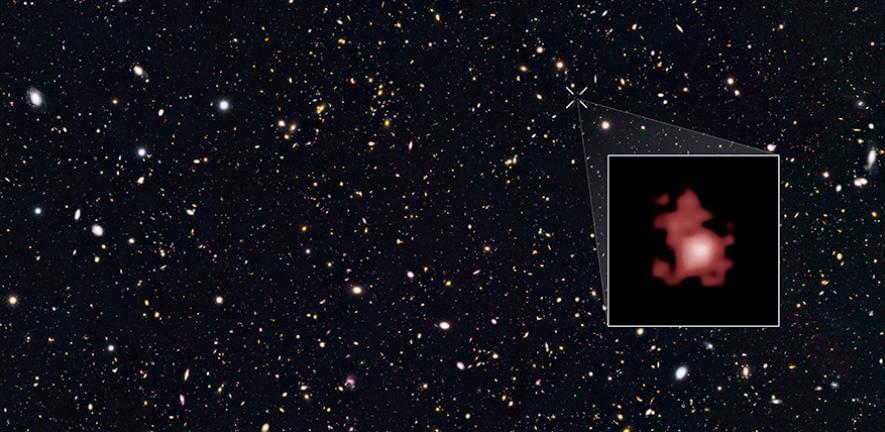

Astronomers have long sought to understand the early universe, and thanks to the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), a critical piece of the puzzle has emerged. The telescope’s infrared detecting “eyes” have spotted an array of small, red dots, identified as some of the earliest galaxies formed in the universe.

This surprising discovery is not just a visual marvel, it’s a clue that could unlock the secrets of how galaxies and their enigmatic black holes began their cosmic journey.

“The astonishing discovery from James Webb is that not only does the universe have these very compact and infrared bright objects, but they’re probably regions where huge black holes already exist,” explains JILA Fellow and University of Colorado Boulder astrophysics professor Mitch Begelman. “That was thought to be impossible.”