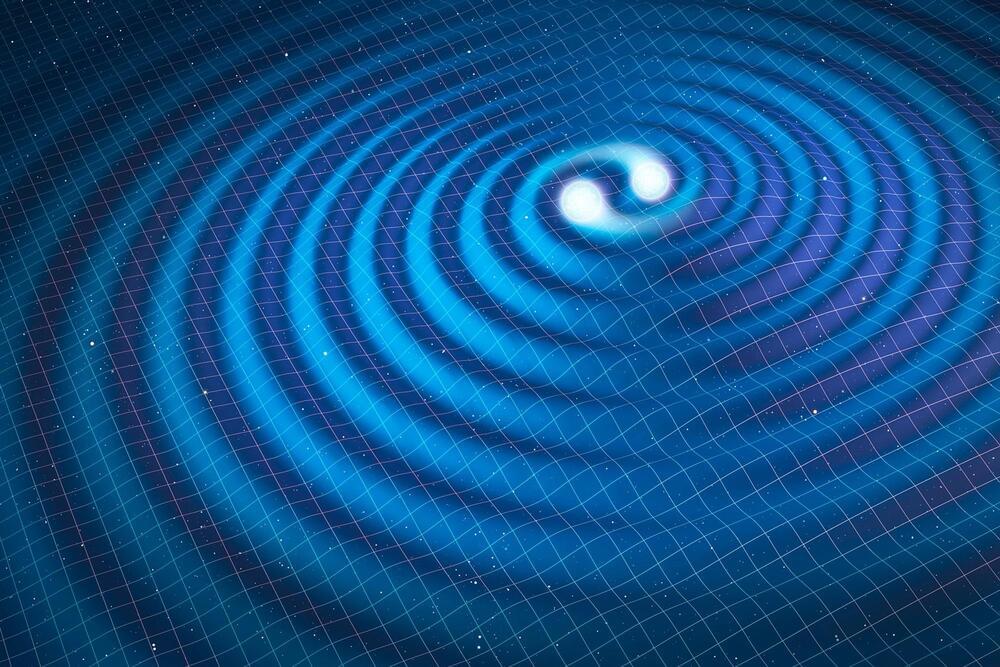

The open CMS detector during the second long shutdown of CERN’s accelerator complex. (Image: CERN) When we look at ourselves in a mirror, we see a virtual twin, identical in every detail except with left and right inverted. In particle physics, a transformation in which charge–parity (CP) symmetry is respected swaps a particle with the mirror image of its antimatter particle, which has opposite properties such as electric charge. The physical laws that govern nature don’t respect CP symmetry, however. If they did, the Universe would contain equal amounts of matter and antimatter, as it is believed to have done just after the Big Bang. To explain the large imbalance between matter and antimatter seen in the present-day Universe, CP symmetry has to be violated to a great extent. The Standard Model of particle physics can account for some CP violation, but it is not sufficient to explain the present-day matter–antimatter imbalance, prompting researchers to explore CP violation in all its known and unknown manifestations. One way CP violation can manifest itself is in the “mixing” of electrically neutral mesons such as the strange beauty meson, which is composed of a strange quark and a bottom antiquark. These mesons can travel macroscopic distances in the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) detectors before decaying into lighter particles, and during this journey they can turn into their corresponding antimesons and back. This phenomenon, called meson mixing, could be different for a meson turning into an antimeson versus an antimeson turning into a meson, generating CP violation. To see if that’s the case, researchers need to count how many mesons or antimesons survive a certain duration before decaying, and then repeat the measurement for a given range of durations. To do so, they have to separate mesons from antimesons, a task called flavour tagging. This task is crucial to pinning down CP violation in meson mixing and in the interference between meson mixing and decay. At a seminar held recently at CERN, the CMS collaboration at the LHC reported the first evidence of CP violation in the decay of the strange beauty meson into a pair of muons and a pair of electrically charged kaons. By deploying a new flavour-tagging algorithm on a sample of about 500 000 decays of the strange beauty meson into a pair of muons and a pair of charged kaons, collected during Run 2 of the LHC, the CMS collaboration measured with improved precision the parameter that determines CP violation in the interference between this meson’s mixing and decay. If this parameter is zero, CP symmetry is respected. The new flavour-tagging algorithm is based on a cutting-edge artificial intelligence (AI) technique called a graph neural network, which performs accurate flavour tagging by gathering information from the particles surrounding the strange beauty meson and those being produced alongside it. The collaboration then combined the result with its previous measurement of the parameter based on data from Run 1 of the LHC. The combined result is different from zero and is consistent with the Standard Model prediction and with previous measurements from CMS and the ATLAS and LHCb experiments. Notably, the combined result is comparable in precision to the world’s most precise measurement of the parameter, obtained by LHCb, a detector specifically designed to perform measurements of this kind. Moreover, the result has a statistical significance that crosses the conventional “3 sigma” threshold, providing the first evidence of CP violation in the decay of the strange beauty meson into a pair of muons and a pair of charged kaons. The result marks a milestone in CMS’s studies of CP violation. Thanks to AI, CMS has pushed the boundary of what its detector can achieve in the exploration of this fundamental matter–antimatter asymmetry. Find out more on the CMS website.