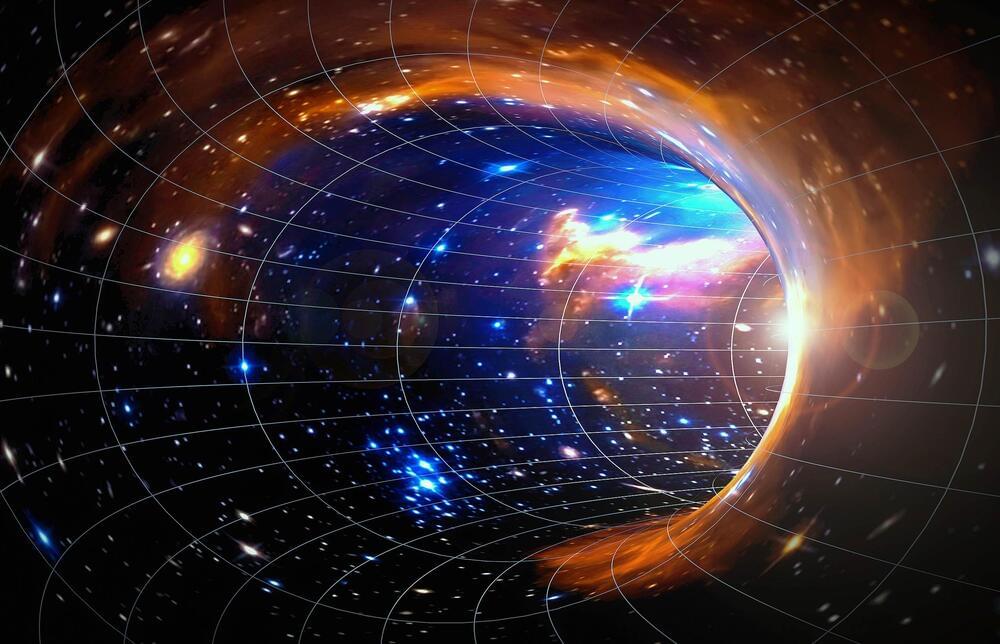

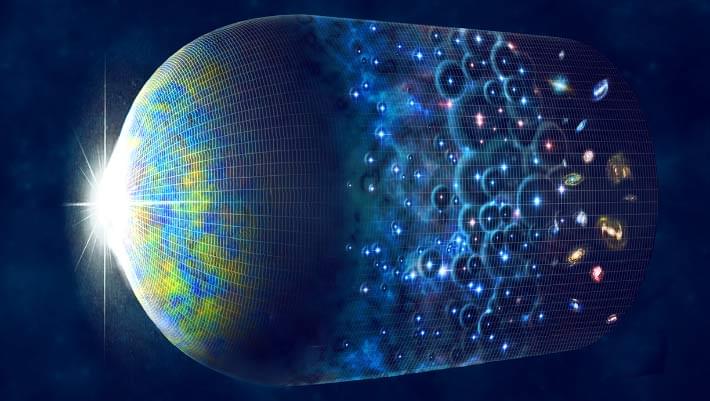

A team of scientists, astrophysicists and physicists, in an experiment called BICEP2 (Background Imaging of Cosmic Extragalactic Polarisation 2), carried out over nine years at an astronomical observatory at the South Pole, reported that they had discovered undeniable traces of a much sought-after phenomenon in astrophysics: gravitational waves. It was also announced that the method used to make the discovery had provided an important confirmation of the theoretical model of Big Bang cosmology, and would allow the first moments after this primordial explosion—the moment of creation for modern astrophysics—to be studied experimentally.

When you don’t find gravitational waves…

If we imagine space and time as the surface of an ocean, gravitational waves can be thought of as ripples in that ocean. More precisely, gravitational waves are theoretical ripples in space-time, first predicted by Albert Einstein in 1916 on the basis of his general theory of relativity. Like electromagnetic waves, which are produced by the oscillation of an electric charge, it is thought that a sufficiently strong oscillation of a very massive object should produce gravitational waves, which carry energy in the form of gravitational energy.