And luckily for us, quantum physicists think they know how to reach that higher dimension.

Category: cosmology – Page 114

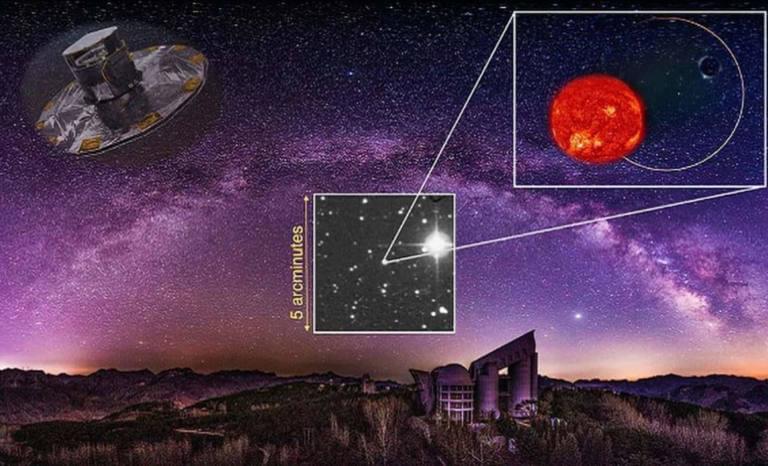

Astronomers Discover a Rare Black Hole That Defies Astrophysical Theories

Chinese astronomers have uncovered a low-mass black hole that challenges long-held astrophysical theories. This black hole, part of a binary system known as G3425, has a mass of about 3.6 solar masses, placing it in the elusive mass-gap where black holes were previously thought to be absent. The discovery was made using a combination of radial velo…

Wormhole: A wormhole is a hypothetical structure connecting disparate points in spacetime, and is based on a special solution of the Einstein field equations

A wormhole is a hypothetical structure connecting disparate points in spacetime, and is based on a special solution of the Einstein field equations. [ 1 ]

A can be visualized as a tunnel with two ends at separate points in spacetime (i.e., different locations, different points in time, or both).

Wormholes are consistent with the general theory of relativity, but whethers actually exist is uncertain. Many scientists postulate thats are merely projections of a fourth spatial dimension, analogous to how a two-dimensional (2D) being could experience only part of a three-dimensional (3D) object. [ 2 ] A well-known analogy of such constructs is provided by the Klein bottle, displaying a hole when rendered in three dimensions but not in four or higher dimensions.

Nobel Winner Warns “IT’S ANOTHER UNIVERSE” James Webb Telescope Saw Strange Things Beyond the…

#webbtelescopeupdates #bigbangtheory #bigbang #astronomy #galaxies #earlyuniverse #nasa #crisisincosmology #Hubbleconstant #expandinguniverse.

Something very strange is happening in the early universe and scientists have no clue why their theories are failing to explain these strange mysteries. Scientists are finding thousands of strange objects in deep field images and they have no idea what exactly they are looking at. They discovered many strange objects in the early universe and scientists said that they cannot be galaxies because these objects are completely different compared to early galaxies. In addition, the Webb telescope looked deep into the universe beyond the Dark Ages for the first time, and what it found has astonished astronomers.

Most scientists agree that the universe began about 13.8 billion years ago. However, the strange structures revealed in these images challenge this timeline and could lead to major shifts in cosmology, the study of the universe’s origin and development.

In light of these groundbreaking observations, several Nobel laureates suggest that the early universe might be vastly different from what we thought. Some even propose the radical idea that the universe may not have had a beginning at all. Instead, they speculate that the distant universe which we are considering as the early universe may actually be something else about which we have no idea.

Cosmology is at a tipping point — we may be on the verge of discovering new physics

“the predictions of the standard model of the universe appear to be at odds with some recent observations.”

Right now, it looks like the cosmology is at a tipping point.

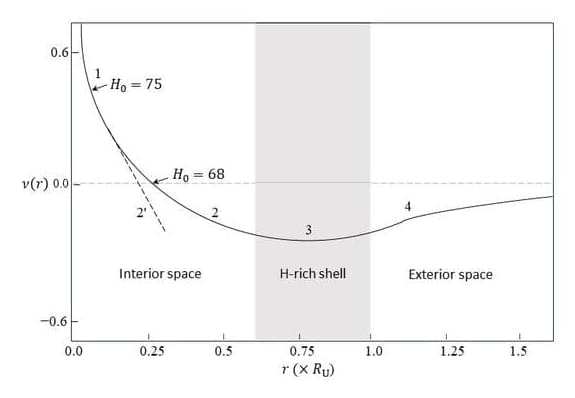

Do we live in a shell universe?

A small black hole must work harder against gravity to keep from collapsing. In rapidly rotating black holes, the Ni shell would collapse to a torus, as possibly reflected in the dramatic photos of supermassive black holes.

At a deeper level, the gravity/Λ mechanism might be seen as a kind of quantum overlay of the Ni solutions, a possible step towards reconciliation of the quantum gravity and general relativity perspectives.

Cosmologists will not be quick to endorse a shell universe. There is still much heavy lifting still to do, for instance, in matching the Ni solutions to the observed universe. Dark matter and dark energy will not lightly be cast aside. But if I am right, the universe is not as you may always have thought.

Is Gravity Quantum or Classical?

👉 Head to https://brilliant.org/spacetime/ for a 30-day free trial + 20% off your annual subscription.

Sign Up on Patreon to get access to the Space Time Discord!

/ pbsspacetime.

If we discover how to connect quantum mechanics with general relativity we’ll pretty much win physics. There are multiple theories that claim to do this, but it’s notoriously difficult to test them. They seem to require absurd experiments like a particle collider the size of a galaxy. Or we could try to physics smarter, instead of physicsing harder. Let’s talk about some ideas for quantum gravity experiments that can be done on a non-galaxy-sized lab bench, and in some cases already have been done.

PBS Member Stations rely on viewers like you. To support your local station, go to: http://to.pbs.org/DonateSPACE

Check out the Space Time Merch Store.

https://www.pbsspacetime.com/shop.

The Universe As An Open System | Denis Noble

Enjoy the videos and music you love, upload original content, and share it all with friends, family, and the world on YouTube.