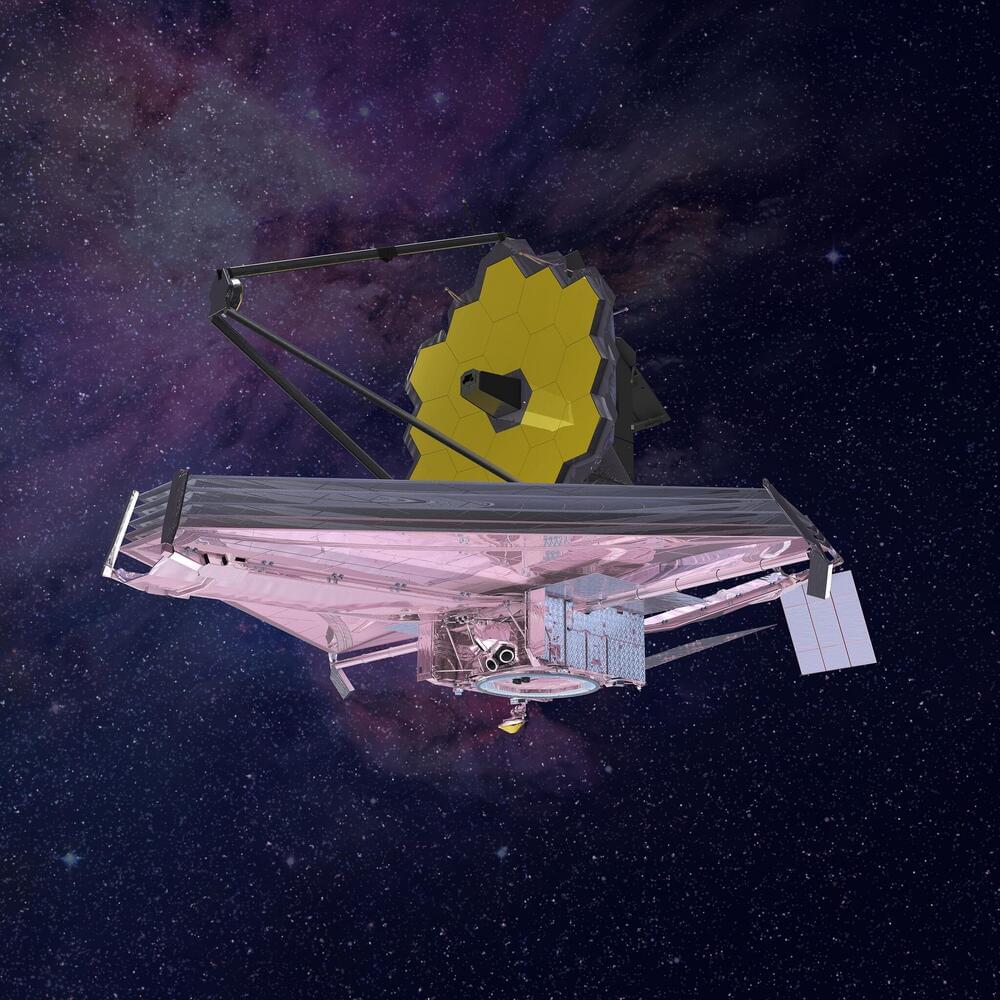

Utilizing the James Webb Space Telescope, astronomers have refined the measurement of the Hubble constant by studying SN H0pe, a gravitationally lensed Type Ia supernova.

This approach, integrating gravitational lensing and time-delay observations, offers a more precise determination of the universe’s expansion rate, helping reconcile some differences between past measurements.

Measuring the Hubble constant, which defines the rate at which the universe is expanding, is a dynamic field of study for astronomers globally. These researchers analyze data from both terrestrial and orbital observatories. NASAs James Webb Space Telescope has already made significant contributions to this discussion. Earlier this year, astronomers employed Webb data that included Cepheid variables and Type Ia supernovae—both reliable cosmic distance markers—to validate previous measurements of the universe’s expansion rate made by NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope.