Circa 2017

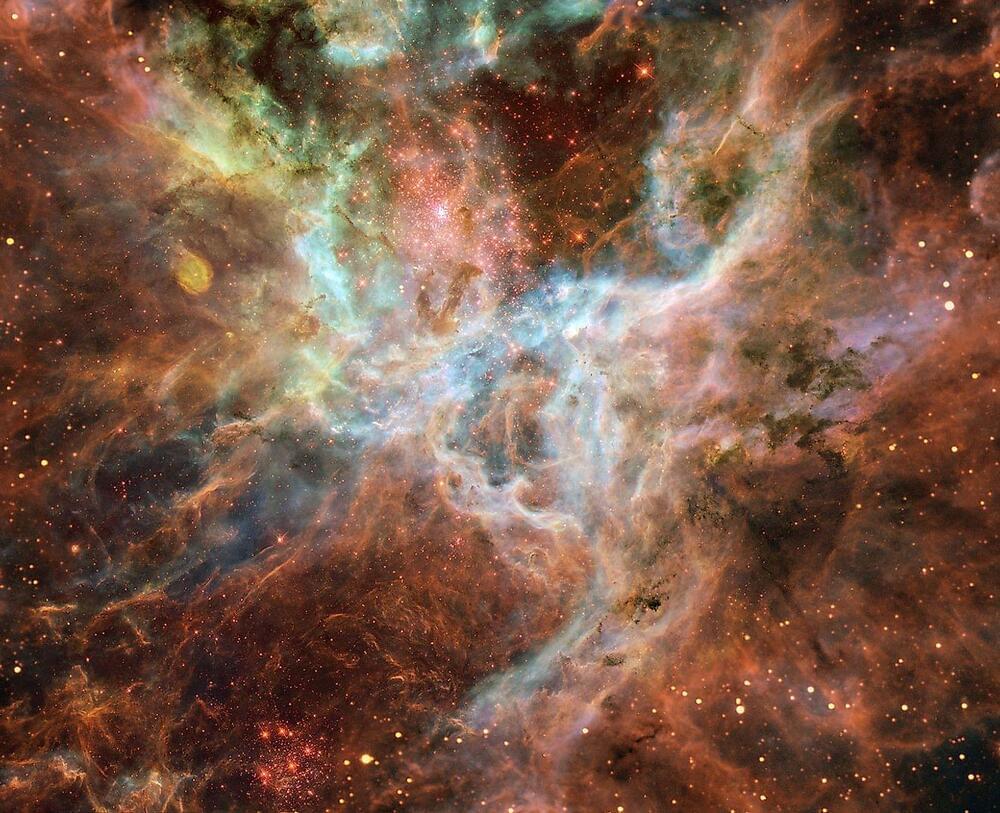

There are many theories about how life evolved on the planet Earth, from formation under a layer of ice, protected from the UV radiation above, to vents in the deep sea that provided hydrogen-rich molecules. But now one team of scientists has found quantitative results that support a theory that is literally out of this world. Organic molecules from meteorites that landed in small, warm pools of water may have delivered the ingredients necessary for life to form on Earth.

The team reached this conclusion through a mathematical model. They took data about planet formation, geology, biology and chemistry and inputted these factors into a grand quantitative model they had designed. Their results support the theory that RNA polymers formed in small, warm ponds of water. Meteorites contributed to this process by transferring enough organic molecules to these pools to ensure that RNA started self-replicating in at least one pool.

What’s more, the team discovered that, according to their calculations, life may have have begun on Earth rather early. The process may have started just a few hundred million years after the planet cooled sufficiently to support liquid surface water. The results were published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.