TISR or video SR (VSR) neural network models are designed to leverage temporal neighbor frames to assist the SR of the current frame and are, therefore, expected to achieve better performance than SISR models19 (Supplementary Note 1). Although TISR models have been widely explored in natural image SR to improve video definition, whether such models can be applied to super-resolve biological images (that is, enhancing both sampling rate and optical resolution) has been poorly investigated. Here, we used the total internal reflection fluorescence (TIRF) SIM, grazing incidence (GI) SIM and nonlinear SIM20 modes of our home-built Multi-SIM system to acquire an extensive TISR dataset of five different biological structures: clathrin-coated pits (CCPs), lysosomes, outer mitochondrial membranes (Mitos), microtubules (MTs) and F-actin filaments (Extended Data Fig. 1). For each type of specimen, we generally acquired over 50 sets of raw SIM images with 20 consecutive time points at 2–4 levels of excitation light intensity (Methods). Each set of raw SIM images was averaged out to a diffraction-limited wide-field (WF) image sequence and was used as the network input, while the raw SIM images acquired at the highest excitation level were reconstructed into SR-SIM images as the ground truth (GT) used in network training. In particular, the image acquisition configuration was modified into a special running order where each illumination pattern is applied 2–4 times at escalating excitation light intensity before changing to the next phase or orientation, so as to minimize the motion-induced difference between WF inputs and SR-SIM targets.

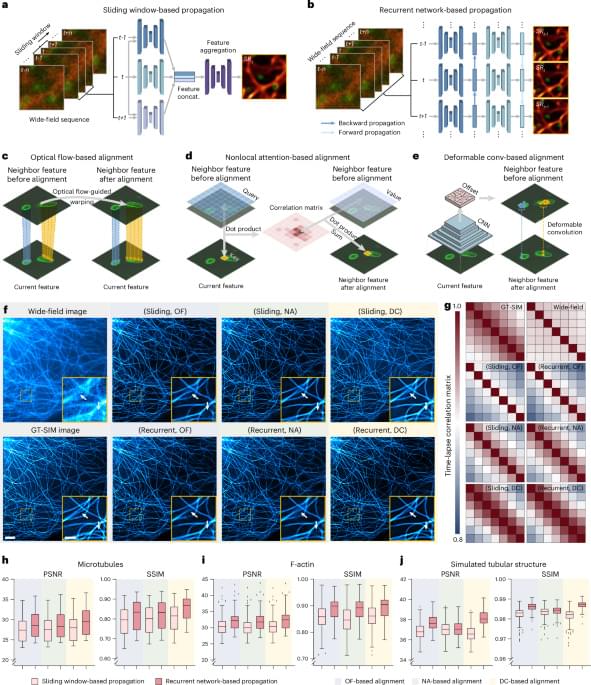

To effectively use the temporal continuity of time-lapse data, SOTA TISR neural networks consist of mainly two important components21,22: temporal information propagation and neighbor feature alignment. We selected two popular types of propagation approaches, sliding window (Fig. 1a) and recurrent network (Fig. 1b), and three representative neighbor feature alignment mechanisms, explicit warping using OF15 (Fig. 1c) and implicit alignment by nonlocal attention23,24 (NA; Fig. 1d) or deformable convolution21,25,26 (DC; Fig. 1e), resulting in six combinations in total. For fair comparison, we custom-designed a general TISR network architecture composed of a feature extraction module, a propagation and alignment module and a reconstruction module (Extended Data Fig. 2) and kept the architecture of the feature extraction module and reconstruction module unchanged while only modifying the propagation and alignment module during evaluation (Methods). We then examined the six models on five different data types: linear SIM data of MTs, lysosomes and Mito, three of the most common biological structures in live-cell experiments, nonlinear SIM data of F-actin, which is of the highest structural complexity and upscaling factor in BioTISR, and simulated data of tubular structure with infallible GT references (Supplementary Note 2). As is shown in Fig. 1f, Extended Data Fig. 3 and Supplementary Fig. 2, all models denoised and sharpened the input noisy WF image evidently, among which the model constructed with a recurrent scheme and DC alignment resolved the finest details compared to the GT-SIM image (indicated by white arrows in Fig. 1f). Furthermore, we calculated time-lapse correlation matrices (Fig. 1g) and image fidelity metrics (Fig. 1h–j) (that is, peak SNR (PSNR) and structural similarity (SSIM)) for the output SR images to quantitatively evaluate the temporal consistency and reconstruction fidelity, respectively. According to the evaluation, we found that recurrent network-based propagation (RNP) outperformed sliding window-based propagation (SWP) in both temporal consistency and image fidelity with fewer trainable parameters (Methods) and propagation mechanisms had little effect on the temporal consistency of the reconstructed SR time-lapse data, while the DC-based alignment generally surpassed the other two mechanisms with a similar number of parameters for all types of datasets (Supplementary Fig. 3).