Like other young researchers, I began my investigation of the brain without worrying much whether this perception-action theoretical framework was right or wrong. I was happy for many years with my own progress and the spectacular discoveries that gradually evolved into what became known in the 1960s as the field of “neuroscience.” Yet my inability to give satisfactory answers to the legitimate questions of my smartest students has haunted me ever since. I had to wrestle with the difficulty of trying to explain something that I didn’t really understand.

Over the years I realized that this frustration was not uniquely my own. Many of my colleagues, whether they admitted it or not, felt the same way. There was a bright side, though, because these frustrations energized my career. They nudged me over the years to develop a perspective that provides an alternative description of how the brain interacts with the outside world.

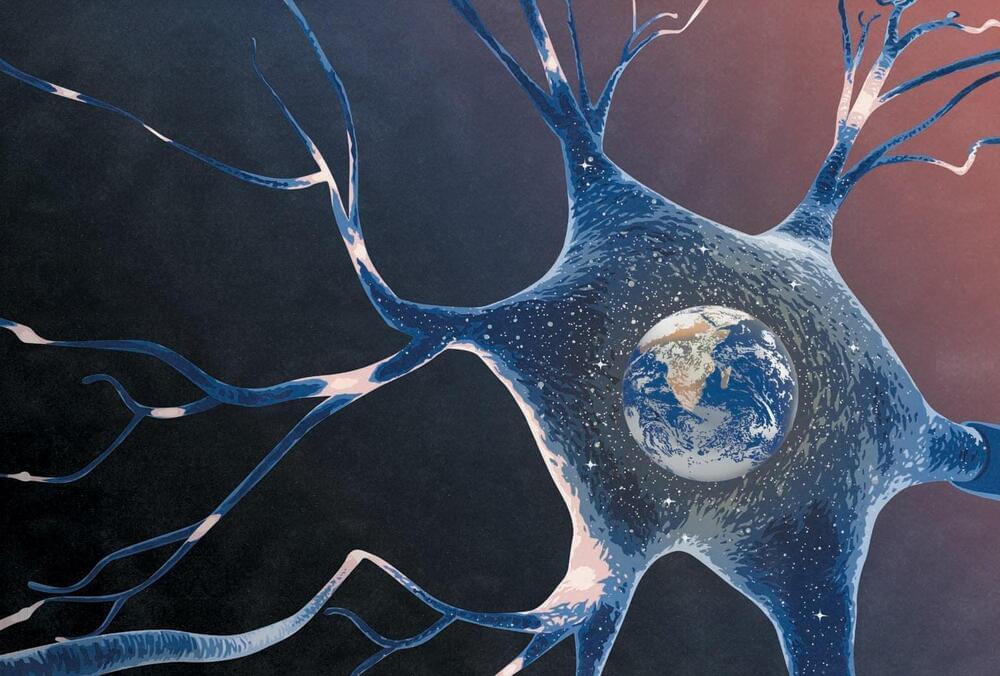

The challenge for me and other neuroscientists involves the weighty question of what, exactly, is the mind. Ever since the time of Aristotle, thinkers have assumed that the soul or the mind is initially a blank slate, a tabula rasa on which experiences are painted. This view has influenced thinking in Christian and Persian philosophies, British empiricism and Marxist doctrine. In the past century it has also permeated psychology and cognitive science. This “outside-in” view portrays the mind as a tool for learning about the true nature of the world. The alternative view—one that has defined my research—asserts that the primary preoccupation of brain networks is to maintain their own internal dynamics and perpetually generate myriad nonsensical patterns of neural activity. When a seemingly random action offers a benefit to the organism’s survival, the neuronal pattern leading to that action gains meaning. When an infant utters “te-te,” the parent happily offers the baby “Teddy,” so the sound “te-te” acquires the meaning of the Teddy bear. Recent progress in neuroscience has lent support to this framework.