In the center of our galaxy, hundreds of stars closely orbit a supermassive black hole. Most of these stars have large enough orbits that their motion is described by Newtonian gravity and Kepler’s laws of motion. But a few orbit so closely that their orbits can only be accurately described by Einstein’s theory of general relativity. The star with the smallest orbit is known as S62. Its closest approach to the black hole has it moving more than 8% of light speed.

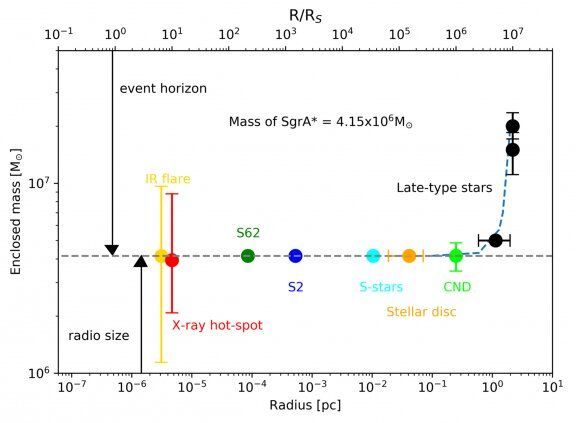

Our galaxy’s supermassive black hole is known as Sagittarius A* (SgrA•. It is a mass of about 4 million suns, and we know this because of the stars that orbit it. For decades, astronomers have tracked the motion of these stars. By calculating their orbits, we can determine the mass of SgrA*. In recent years, our observations have become so precise that we can measure more than the black hole’s mass. We can test whether our understanding of black holes is accurate.

The most studied star orbiting SgrA* is known as S2. It is a bright, blue giant star that orbits the black hole every 16 years. In 2018, S2 made its closest approach to the black hole, giving us a chance to observe an effect of relativity known as gravitational redshift. If you toss a ball up into the air, it slows down as it rises. If you shine a beam of light into the sky, the light doesn’t slow down, but gravity does take away some of its energy. As a result, a beam of light becomes redshifted as it climbs out of a gravitational well. This effect has been observed in the lab, but S2 gave us a chance to see it in the real world. Sure enough, at the close approach, the light of S2 shifted to the red just as predicted.