Infections caused by Cryptococcus are extremely dangerous. The pathogen, which can cause pneuomia-like symptoms, is notoriously drug-resistant, and it often preys on people with weakened immune systems, like cancer patients or those living with HIV. And the same can be said about other fungal pathogens, like Candida auris or Aspergillus fumigatus — both of which, like Cryptococcus, have been declared priority pathogens by the World Health Organization.

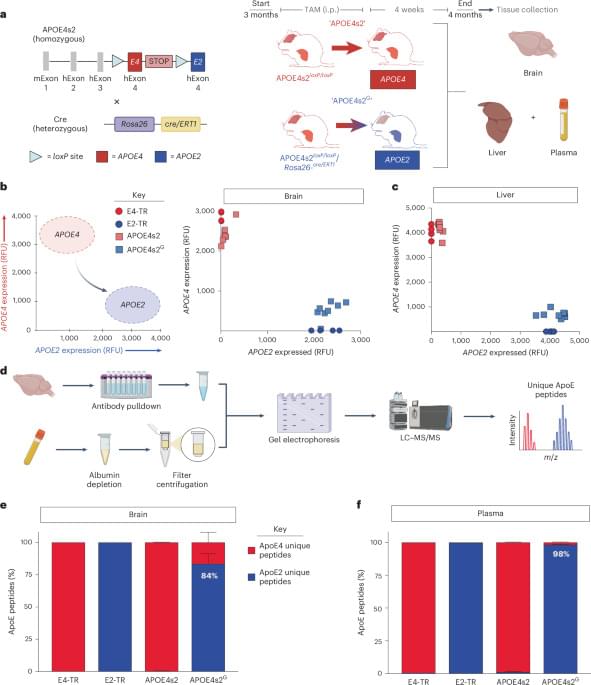

Despite the threat, though, doctors have only three treatment options for fungal infections.

The gold standard is a drug class called amphotericin but has major toxic side-effects on humans.

The other two antifungal drug classes that are available — azoles and echinocandins — are much less effective treatment options, especially against Cryptococcus. The author says azoles merely stop fungi from growing rather than outright killing them, while Cryptococcus and other fungi have become totally resistant to echinocandins, rendering them completely ineffective.

“Adjuvants are helper molecules that don’t actually kill pathogens like drugs do, but instead make them extremely susceptible to existing medicine,” explains the author.

Looking for adjuvants that might better sensitize Cryptococcus to existing antifungal drugs, the lab screened vast chemical collection for candidate molecules.

Quickly, the team found a hit: butyrolactol A, a known-but-previously understudied molecule produced by certain Streptomyces bacteria. The researchers found that the molecule could synergize with echinocandin drugs to kill fungi that the drugs alone could not.