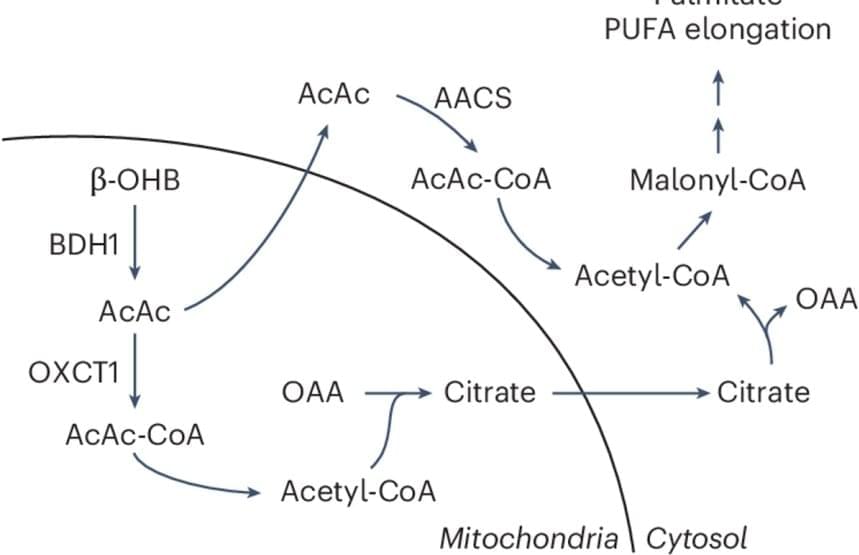

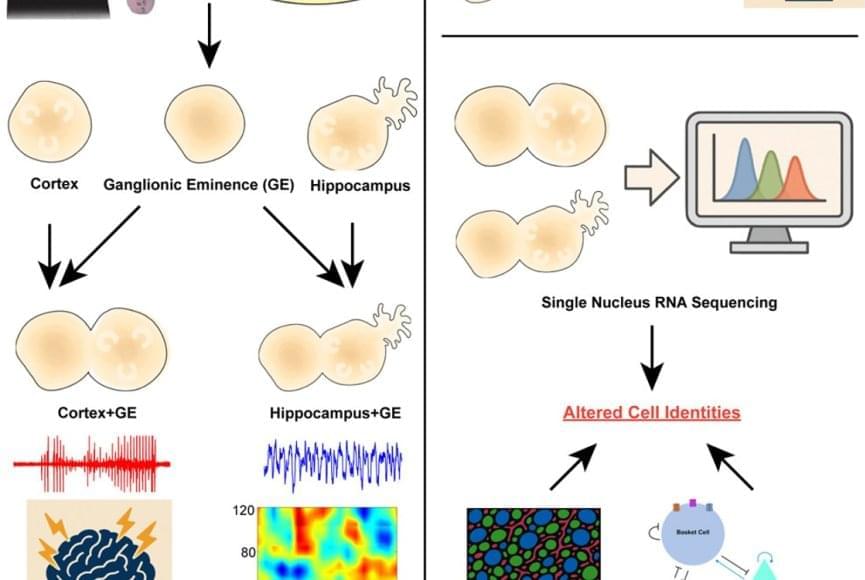

Using patient-derived induced pluripotent stem cells, the researchers generated advanced models known as 3D assembloids of two key brain areas: the cortex, which is essential for movement and higher-order thinking, and the hippocampus, which supports learning and memory. The results revealed strikingly different effects depending on the brain region.

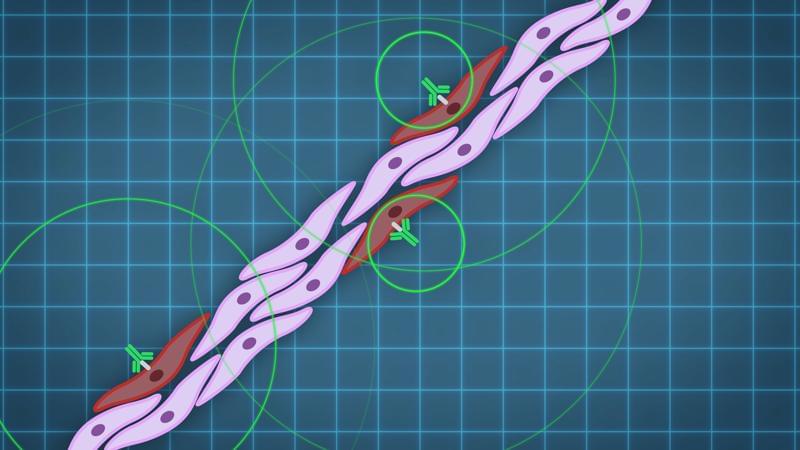

In cortical models, the SCN8A variants made neurons hyperactive, mimicking seizure activity. In hippocampal models, however, the variants disrupted the brain rhythms associated with learning and memory. This disruption stemmed from a selective loss of specific hippocampal inhibitory neurons — the brain’s traffic cops that regulate neural activity.

These findings may help explain why patients with epilepsy often struggle with symptoms beyond seizures.

To confirm their findings, the researchers compared brain recordings from people with epilepsy to stem cell-derived hippocampal assembloids. They looked at seizure-prone regions of the patients’ hippocampi as well as regions unaffected by seizures. Abnormal brain rhythms appeared in both the patients’ seizure “hot spots” and in assembloids carrying SCN8A variants. In contrast, seizure-free brain regions and assembloids without the variants showed normal activity.

For families of children with severe epilepsy, controlling seizures is often just the beginning of their challenges. Even in cases where powerful medications can reduce seizures, many children continue to face difficulties with learning, behavior and sleep that can be just as disruptive to daily life.

New stem cell-based research published in Cell Reports, provides an early step toward understanding why current treatments often fall short, pointing to the distinct effects that single disease-causing gene variants can have across different regions of the brain.