In 2000, researchers discovered that mutations that inactivate a gene known as TRIM37 cause a developmental disease called Mulibrey nanism. The extremely rare inherited disorder leads to growth delays and abnormalities in several organs, causing afflictions of the heart, muscles, liver, brain and eyes. In addition, Mulibrey nanism patients exhibit high rates of cancer and are infertile.

In 2016, UC San Diego School of Biological Sciences researchers in the labs of Professors Karen Oegema and Arshad Desai began understanding how TRIM37, when operating normally, plays a key role in preventing conditions that lead to Mulibrey nanism. They linked TRIM37 to spindles, which separate chromosomes during cell division, and centrosomes, the spherical organizing structures at each end of spindles.

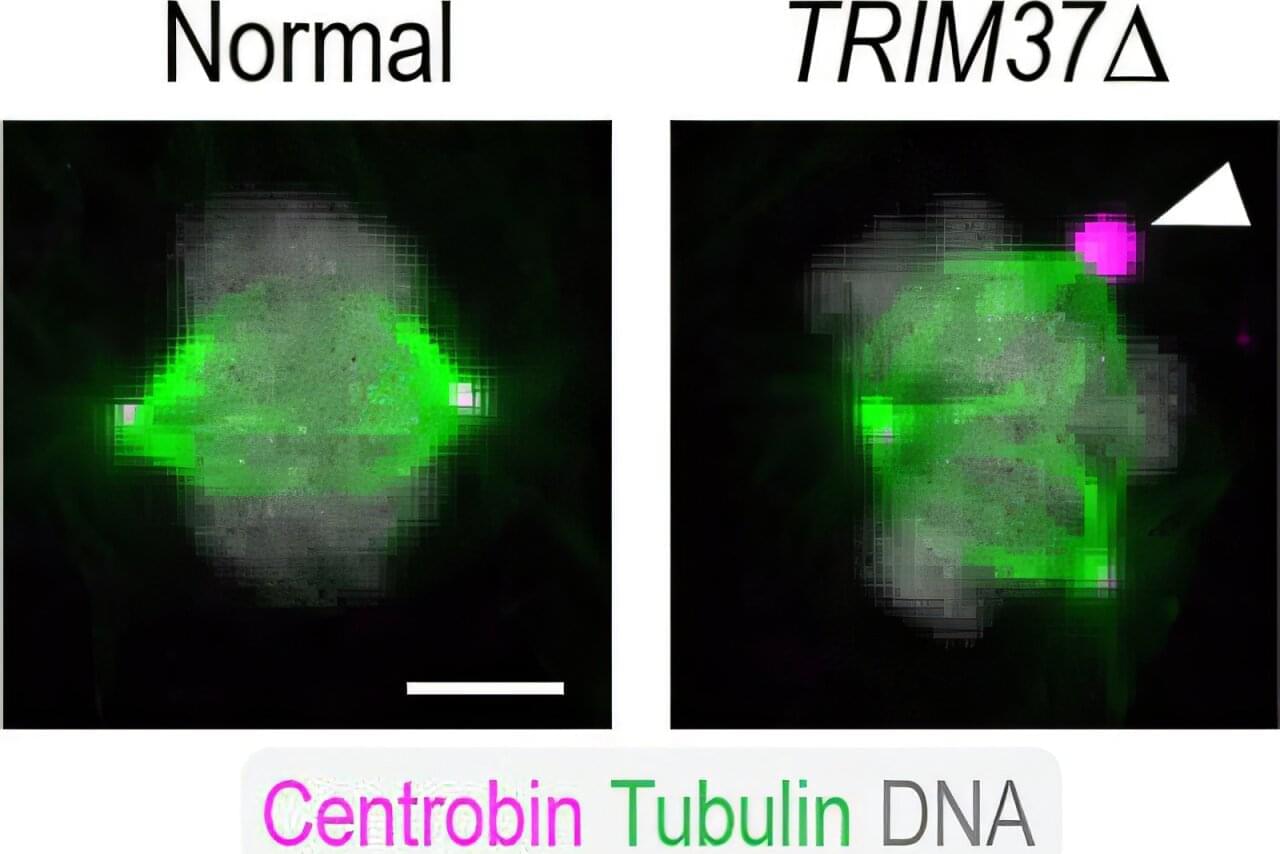

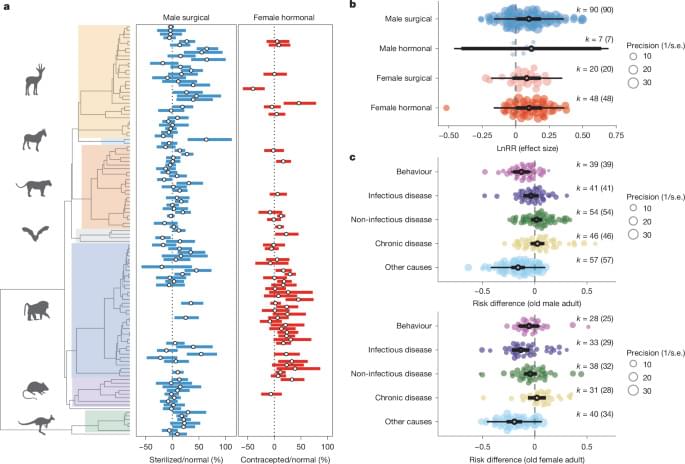

The image above shows a normal mitotic cell (left) compared to a cell lacking TRIM37 (right), with spindle microtubules (green), centrosomal protein centrobin (magenta) and DNA (white). Normal cells have two spindle poles that ensure proper cell division. Cells lacking TRIM37 frequently have extra spindle poles, containing a cluster of centrobin molecules that disrupt proper cell division. Patients with Mulibrey nanism lack TRIM37 and their cells show similar extra spindle poles.