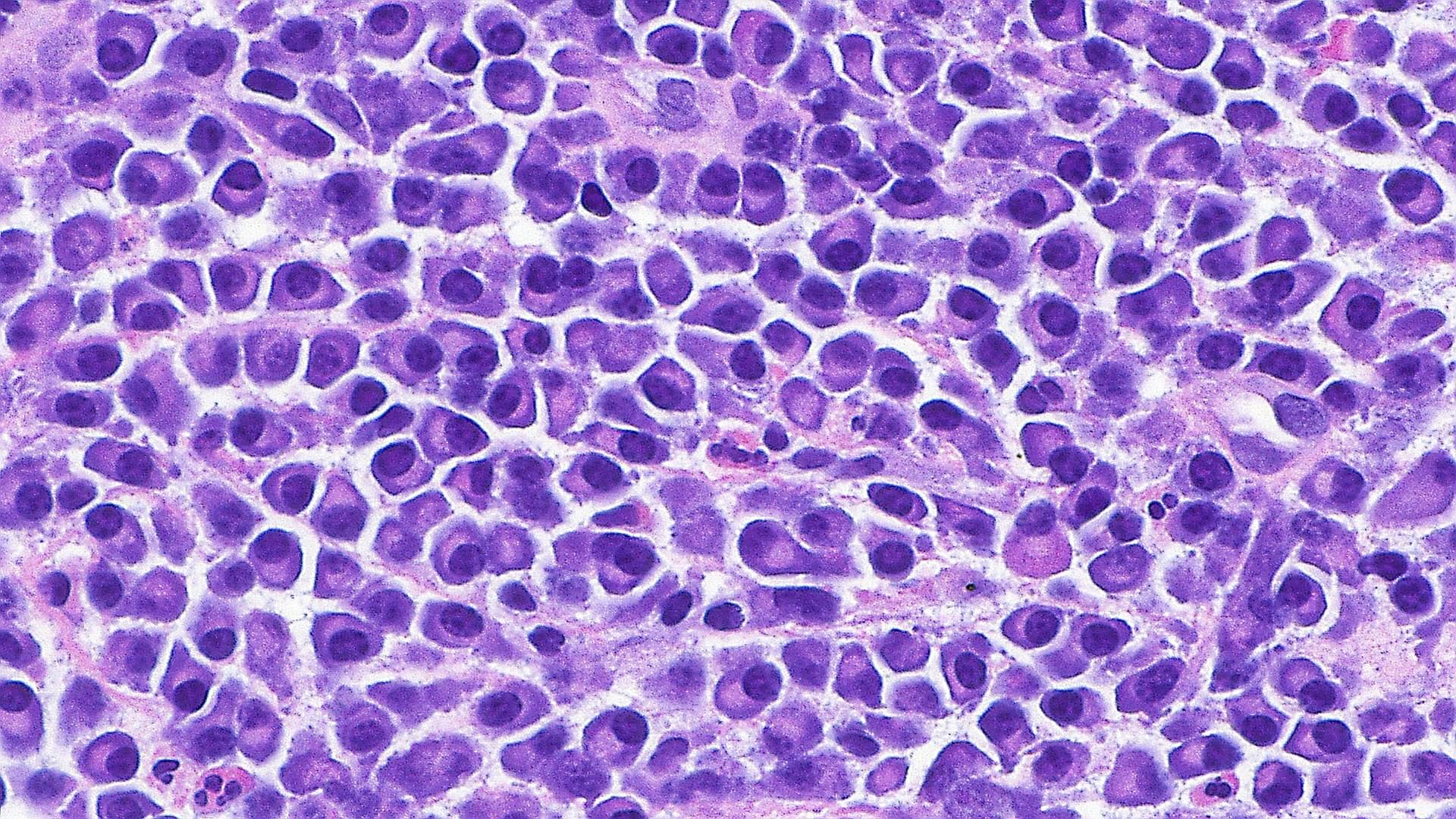

Temporal lobe epilepsy, which results in recurring seizures and cognitive dysfunction, is associated with premature aging of brain cells.

A new study by researchers at Georgetown University Medical Center found that this form of epilepsy can be treated in mice by either genetically or pharmaceutically eradicating the aging cells, thereby improving memory and reducing seizures as well as protecting some animals from developing epilepsy.

The study appears in the journal Annals of Neurology.