For a heavy drinker whose liver has been destroyed by alcohol, an organ transplant is often the only realistic option. But because of donor liver shortages and rules that withhold them from people who have not shed their alcohol addiction, many go without. Tens of thousands die from alcoholic liver disease each year in the United States—and some go downhill much faster than others. Now, scientists have found a reason for this disparity: a toxin produced by some strains of a common gut bacterium. Working in mice, they have also tested a potential therapy, based on bacteria-destroying viruses found lurking in the sewer.

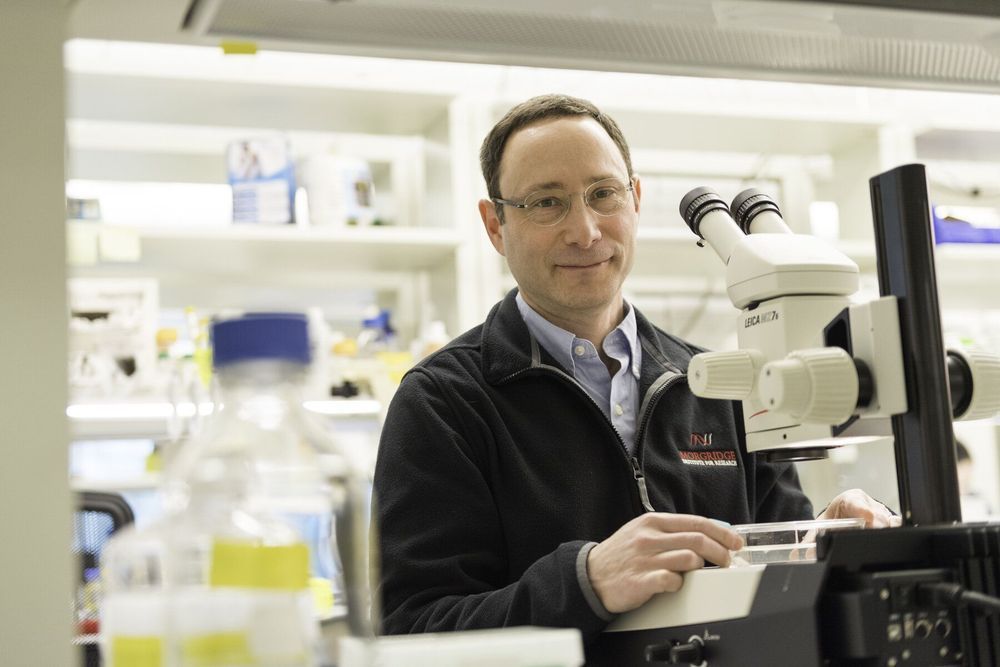

Why some drinkers with liver disease fare much worse than others “has always been a conundrum,” says Jasmohan Bajaj, a gastroenterologist and liver specialist at Virginia Commonwealth University in Richmond. The bacterium Enterococcus faecalis offers an explanation, Bernd Schnabl, a gastroenterologist at the University of California, San Diego (UCSD), School of Medicine, and colleagues report this week in Nature. In fecal samples from patients with alcoholic liver disease, levels of it were 2700 times higher than in nondrinkers, although the mere quantity didn’t correlate with a person’s outcome. Instead, the researchers identified a cell-destroying toxin called cytolysin produced by select strains of E. faecalis as the likely reason that some patients with alcoholic liver disease had severe symptoms.

Fewer than 5% of healthy people carry the toxinmaking strains, but the group found them in 30% of the people hospitalized with alcoholic liver disease whom they tested. And those patients had a much higher mortality rate within 180 days of admission—89% of the cytolysin-positive patients died compared with only 3.8% of the other patients. “Cytolysin is a factor that really drives mortality and liver disease severity,” Schnabl says.