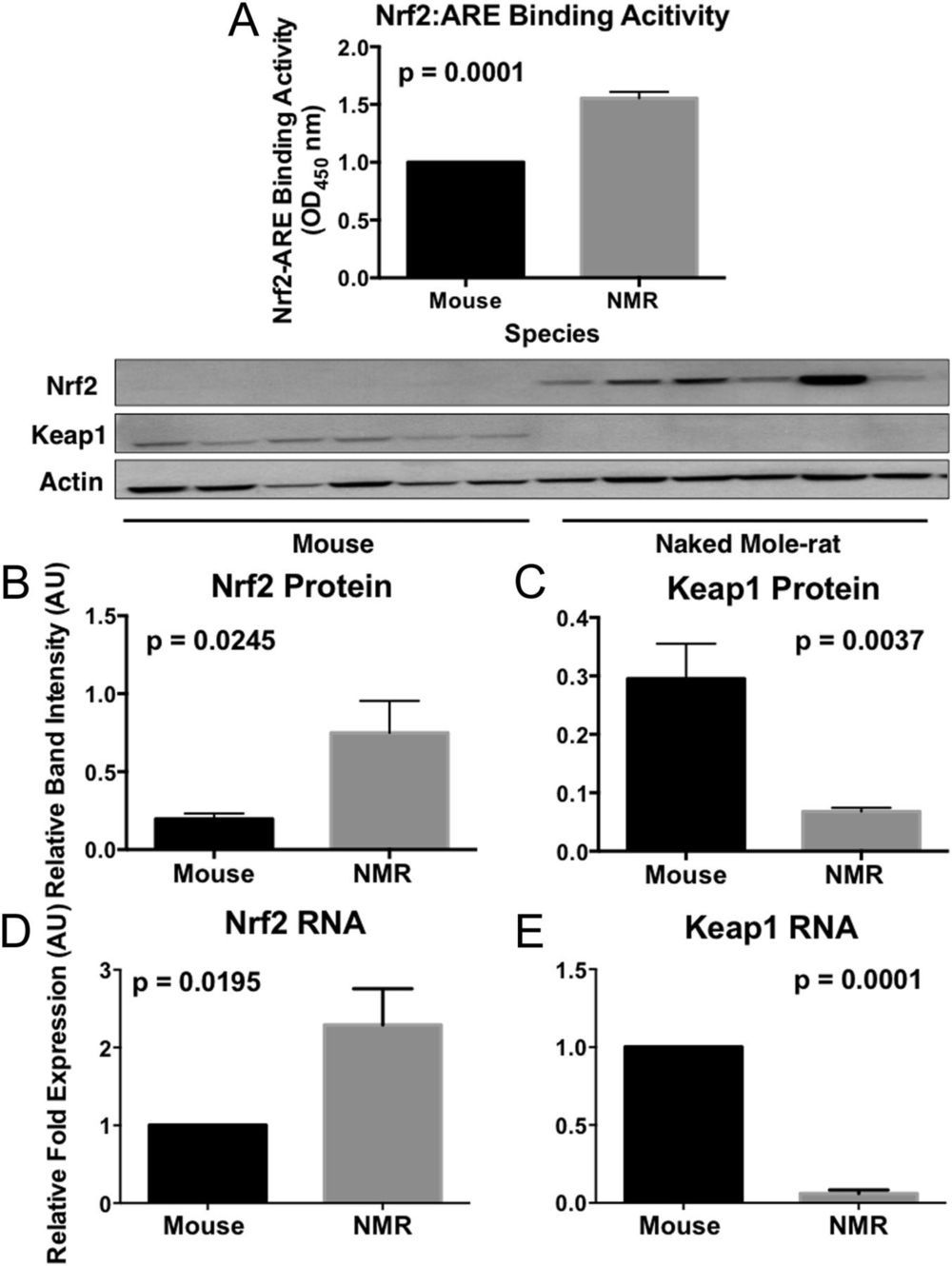

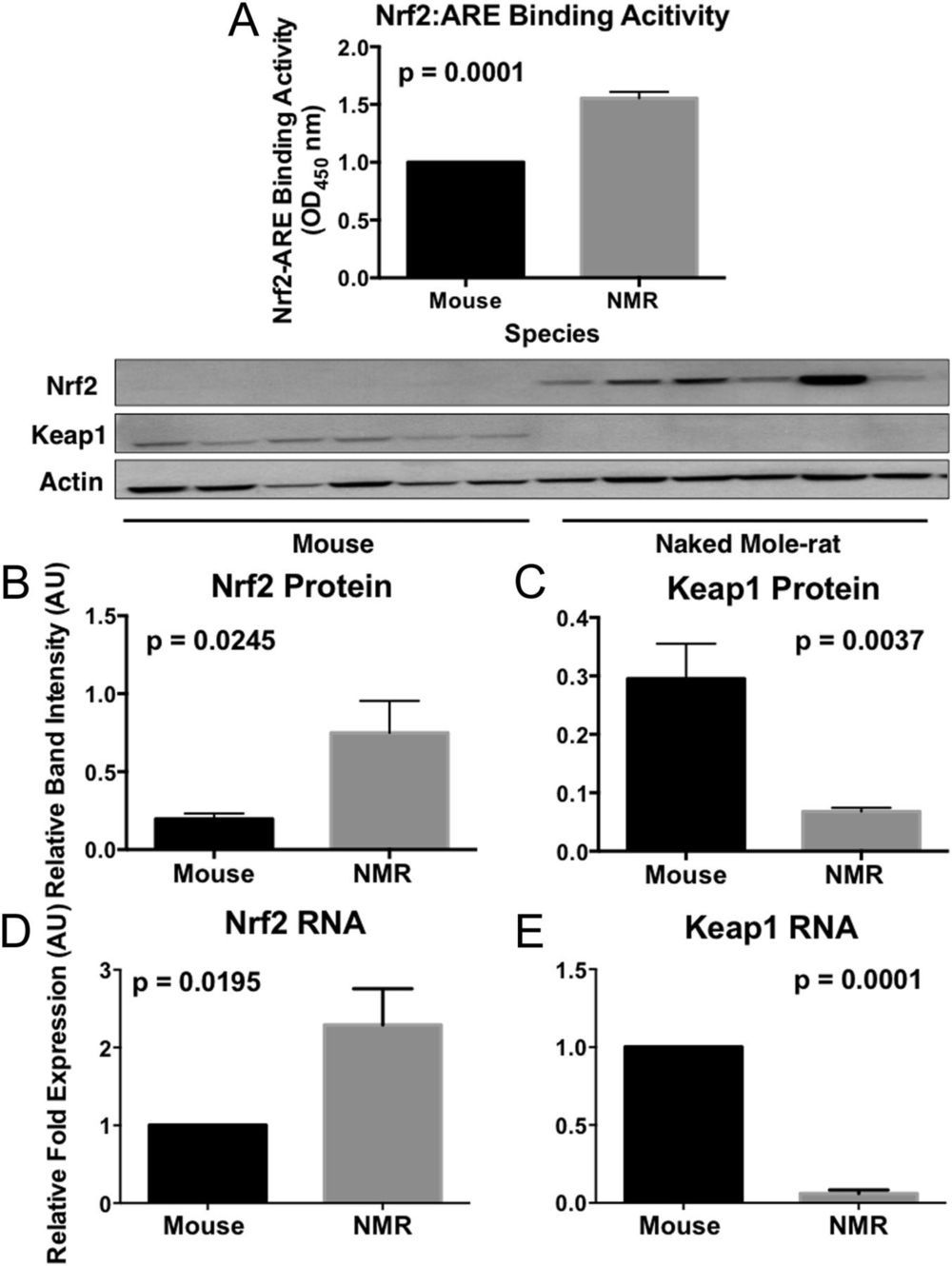

Both genetically altered and naturally long-lived mammals are more resistant to toxic compounds that may cause cancer and age-associated diseases than their shorter-lived counterparts. The mechanisms by which this stress resistance occurs remain elusive. We found that longer-lived rodent species had markedly higher levels of signaling activity of the multifunctional regulator nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor (Nrf2) and that this increase in cytoprotective signaling appeared to be due to species differences in Kelch-like ECH-Associated Protein 1 (Keap1) and β-transducin repeat-containing protein (βTrCP) regulation of Nrf2 activity. Both of these negative regulators of Nrf2-signaling activity are significantly lower in longer-lived species. By targeting the proteins that regulate Nrf2 rather than Nrf2 itself, we may be able to identify new therapies that impact aging and age-associated diseases such as cancer.

The preternaturally long-lived naked mole-rat, like other long-lived species and experimental models of extended longevity, is resistant to both endogenous (e.g., reactive oxygen species) and environmental stressors and also resists age-related diseases such as cancer, cardiovascular disease, and neurodegeneration. The mechanisms behind the universal resilience of longer-lived organisms to stress, however, remain elusive. We hypothesize that this resilience is linked to the activity of a highly conserved transcription factor, nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor (Nrf2). Nrf2 regulates the transcription of several hundred cytoprotective molecules, including antioxidants, detoxicants, and molecular chaperones (heat shock proteins). Nrf2 itself is tightly regulated by mechanisms that either promote its activity or increase its degradation.

O.o.

O.o.