Before there were animals, bacteria or even DNA on Earth, self-replicating molecules were slowly evolving their way from simple matter to life beneath a constant shower of energetic particles from space.

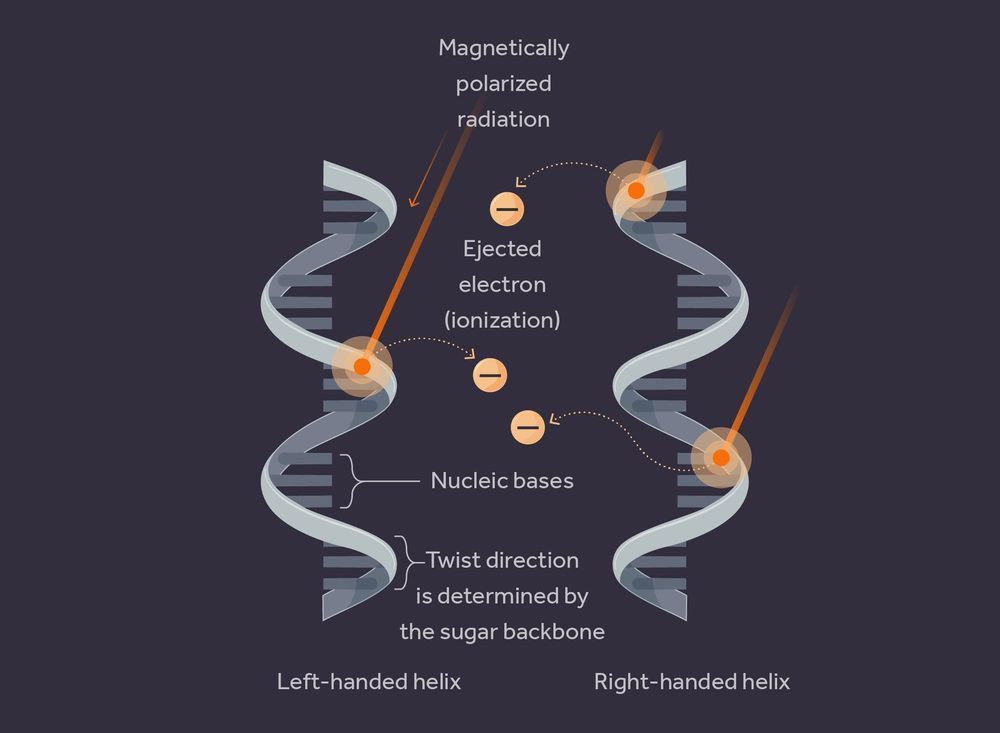

In a new paper, a Stanford professor and a former post-doctoral scholar speculate that this interaction between ancient proto-organisms and cosmic rays may be responsible for a crucial structural preference, called chirality, in biological molecules. If their idea is correct, it suggests that all life throughout the universe could share the same chiral preference.

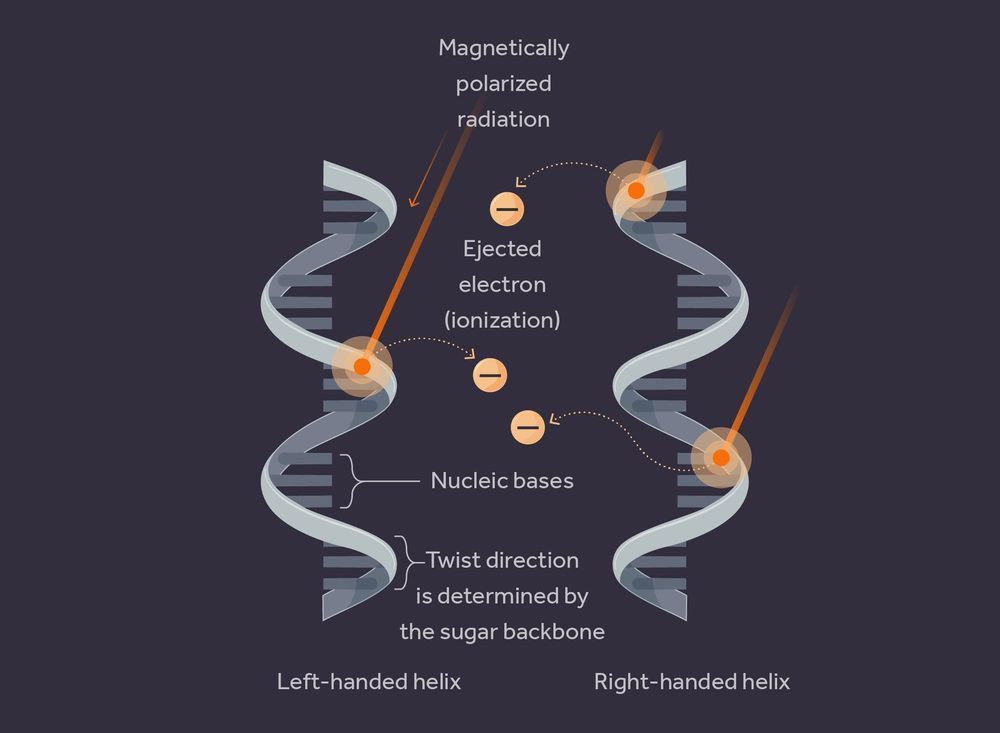

Chirality, also known as handedness, is the existence of mirror-image versions of molecules. Like the left and right hand, two chiral forms of a single molecule reflect each other in shape but don’t line up if stacked. In every major biomolecule—amino acids, DNA, RNA—life only uses one form of molecular handedness. If the mirror version of a molecule is substituted for the regular version within a biological system, the system will often malfunction or stop functioning entirely. In the case of DNA, a single wrong handed sugar would disrupt the stable helical structure of the molecule.