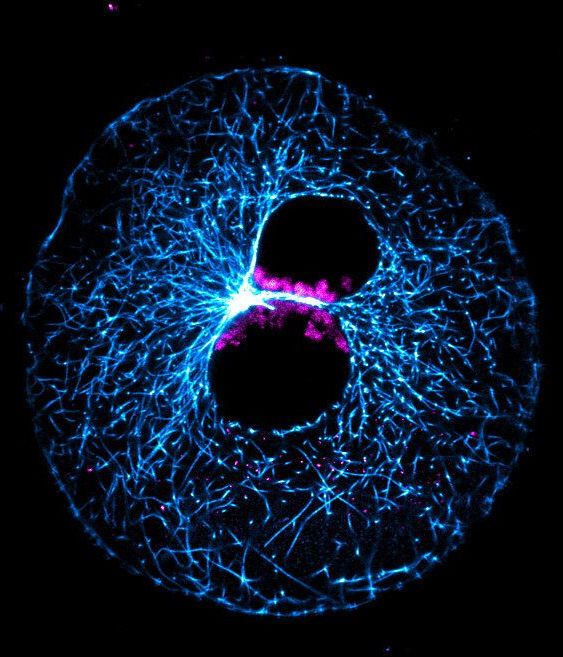

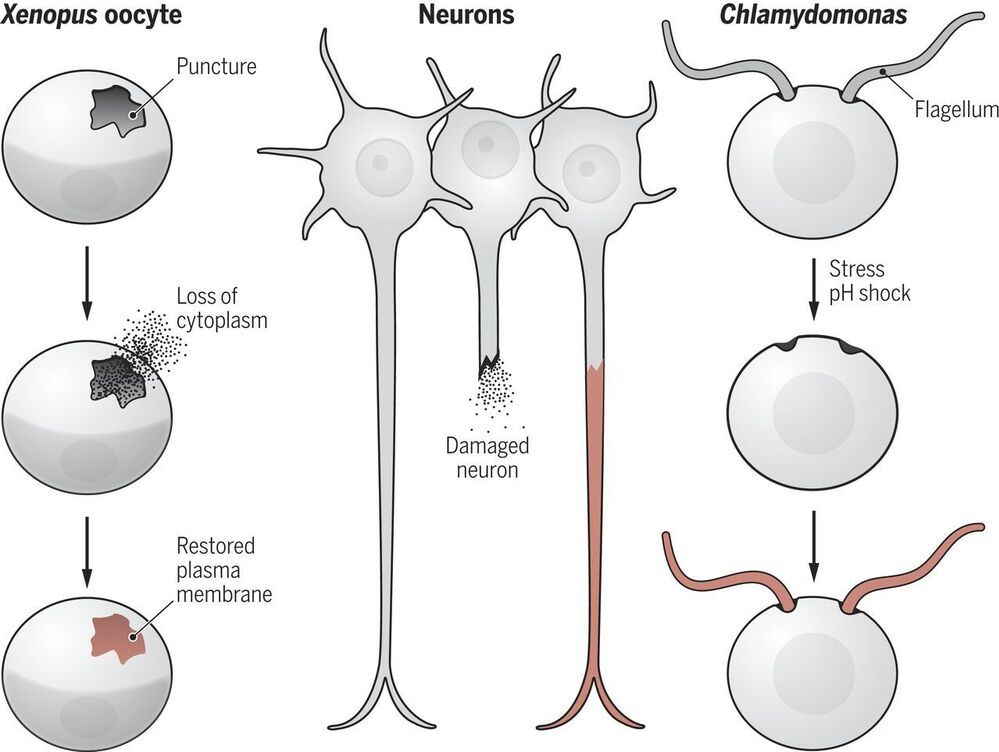

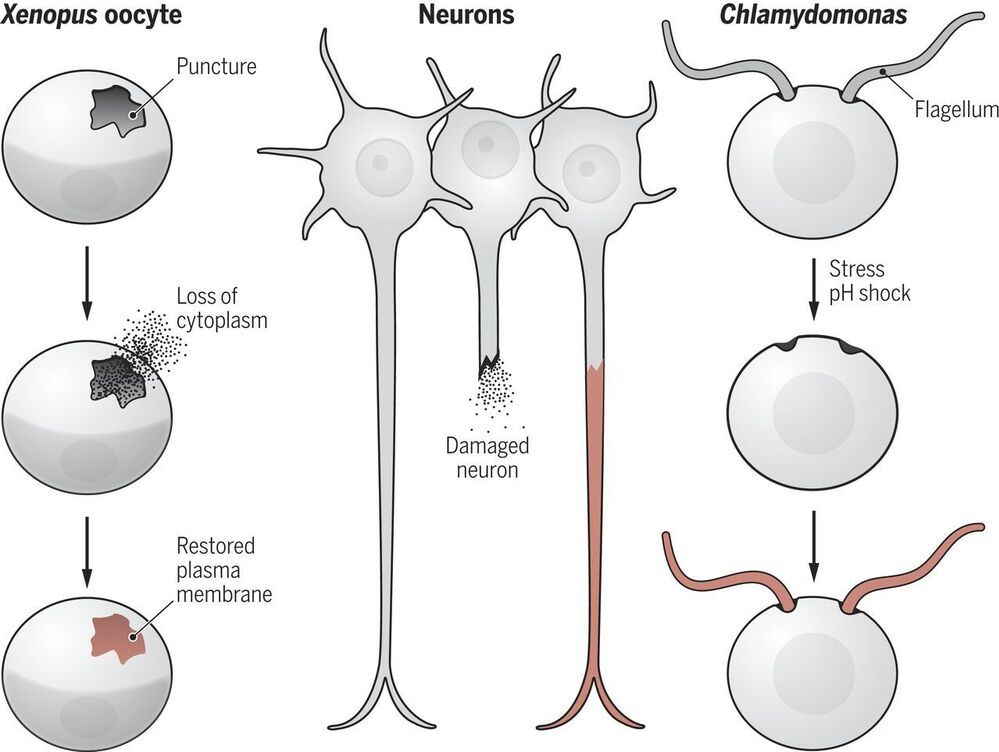

Many organisms and tissues display the ability to heal and regenerate as needed for normal physiology and as a result of pathogenesis. However, these repair activities can also be observed at the single-cell level. The physical and molecular mechanisms by which a cell can heal membrane ruptures and rebuild damaged or missing cellular structures remain poorly understood. This Review presents current understanding in wound healing and regeneration as two distinct aspects of cellular self-repair by examining a few model organisms that have displayed robust repair capacity, including Xenopus oocytes, Chlamydomonas, and Stentor coeruleus. Although many open questions remain, elucidating how cells repair themselves is important for our mechanistic understanding of cell biology. It also holds the potential for new applications and therapeutic approaches for treating human disease.

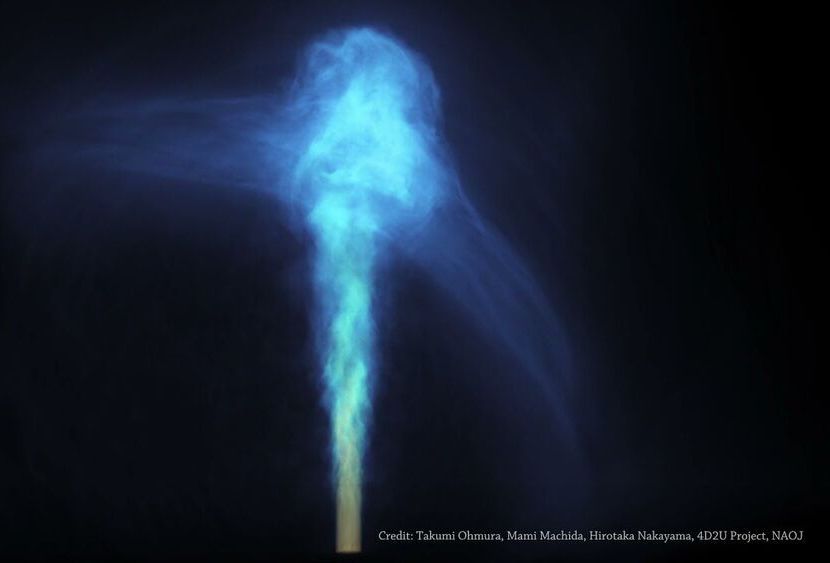

Cells are generally soft and easily damaged. However, many can repair themselves after being punctured, torn, or even ripped in half when damaged during the ordinary wear and tear of normal physiology or as a result of injury or pathology. A cell is like a spacecraft: When it is punctured, cytoplasm spills out like oxygen escaping from a damaged space module. Like Apollo 13, a damaged cell cannot rely on anyone to fix it. It must repair itself, first by stopping the loss of cytoplasm, and then regenerate by rebuilding structures that were damaged or lost. Knowledge of how single cells repair and regenerate themselves underpins our mechanistic understanding of cell biology and could guide treatments for conditions involving cellular damage.

A standard question that students are asked is to define what it means to be alive. This is surprisingly hard to answer in a precise way, but surely one of the remarkable features of living systems that distinguishes them from human-made machines is their ability to heal and repair themselves. At the multicellular level, repair and regeneration are effected by generating new cells to replace the ones that were lost. This type of repair thus ends up being a direct consequence of another basic feature of living systems—the ability of a cell to reproduce itself. No additional processes need to be invoked beyond cell division. At the single-cell level, it is much less obvious how self-repair is accomplished.