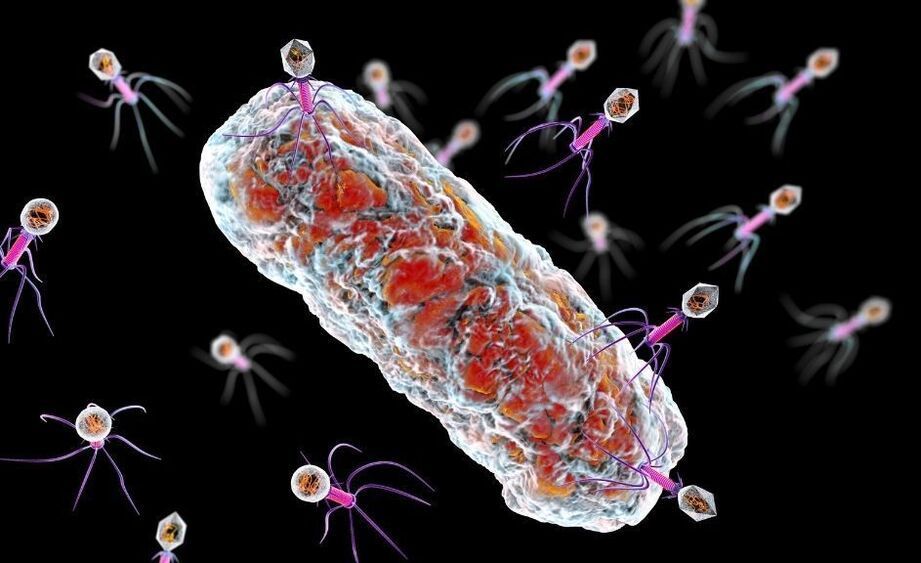

For the first time ever, researchers from the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine discovered that phages — tiny viruses that attack bacteria — are key to initiating rapid bacterial evolution leading to the emergence of treatment-resistant “superbugs.” The findings were published today in Science Advances.

The researchers showed that, contrary to a dominant theory in the field of evolutionary microbiology, the process of adaptation and diversification in bacterial colonies doesn’t start from a homogenous clonal population. They were shocked to discover that the cause of much of the early adaptation wasn’t random point mutations. Instead, they found that phages, which we normally think of as bacterial parasites, are what gave the winning strains the evolutionary advantage early on.

“Essentially, a parasite became a weapon,” said senior author Vaughn Cooper, Ph.D., professor of microbiology and molecular genetics at Pitt. “Phages endowed the victors with the means of winning. What killed off more sensitive bugs gave the advantage to others.”