Researchers at the Kennedy Institute of Rheumatology have found that physically resisting the formation of an immunological synapse actually promotes a stronger immune response. The findings could help explain how immune responses become weakened in cancer and chronic infection and inform the design of more effective vaccines.

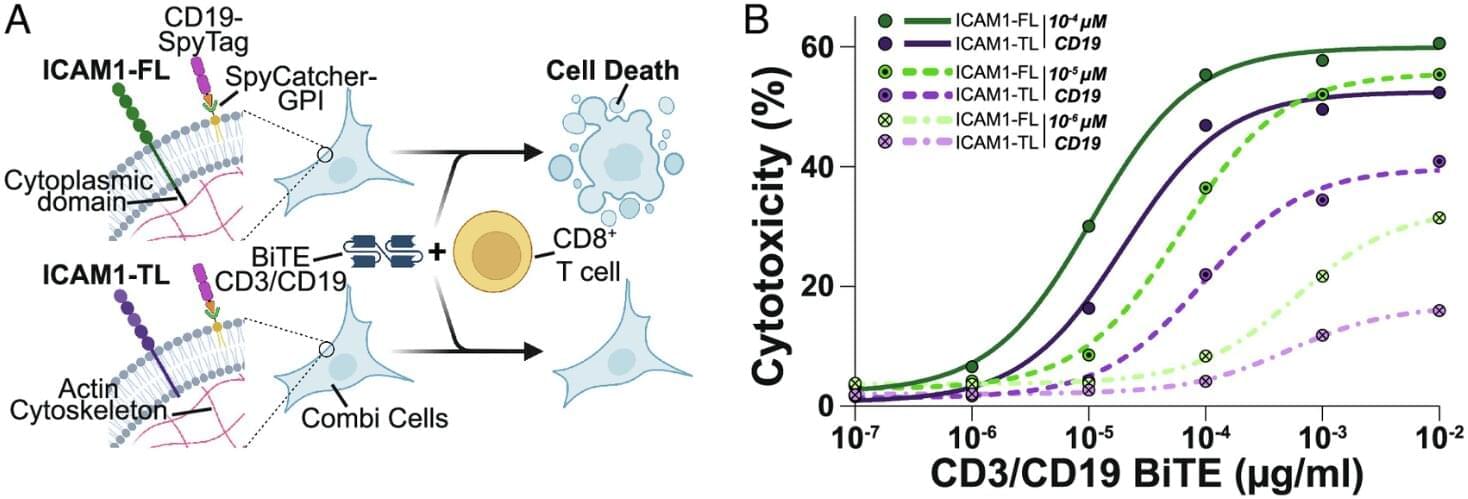

In a new study led by Professor Mike Dustin at the Kennedy Institute, and the team lead Dr. Alexander Leithner (now at the University of Salzburg, Austria), in collaboration with Audun Kvalvaag, at the Institute for Cancer Research at the University Hospital Oslo, examined how the physical presentation of a protein called ICAM-1 (Intercellular Adhesion Molecule 1) on a target cells affects the activation of T cells—the immune system’s cells responsible for identifying and eliminating infected or cancerous cells.

Published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, their findings show that when ICAM-1 is locked in place, rather than free to move within the cell membrane, T cells show a stronger response and become more effective at killing target cells. The study provides new insight that could help design better immune strategies and may have implications for vaccine design, cancer immunotherapy and understanding immune evasion.