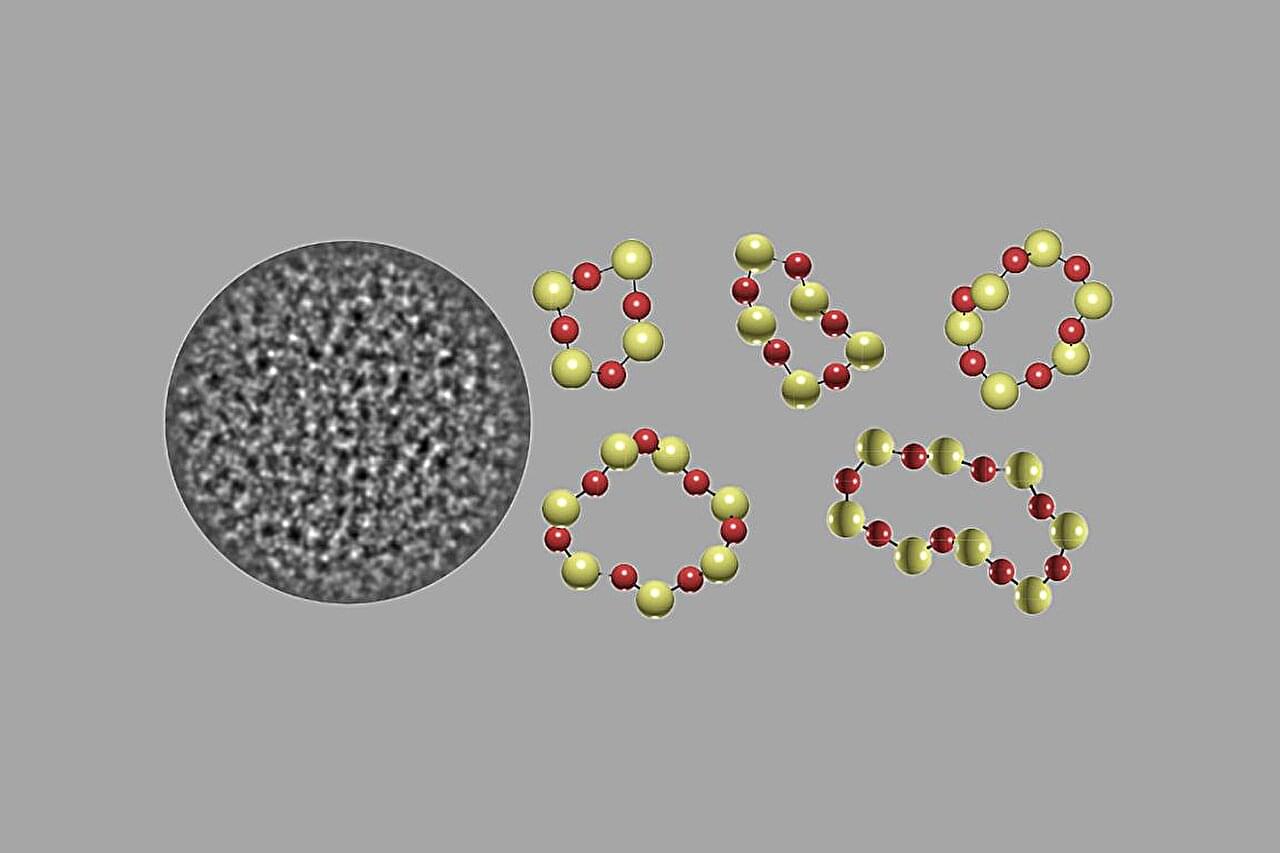

Physical systems become inherently more complicated and difficult to produce in a lab as the number of dimensions they exist in increases—even more so in quantum systems. While discrete time crystals (DTCs) had been previously demonstrated in one dimension, two-dimensional DTCs were known to exist only theoretically. But now, a new study, published in Nature Communications, has demonstrated the existence of a DTC in a two-dimensional system using a 144-qubit quantum processor.

Like regular crystalline materials, DTCs exhibit a kind of periodicity. However, the crystalline materials most people are familiar with have a periodically repeating structure in space, while the particles in DTCs exhibit periodic motion over time. They represent a phase of matter that breaks time-translation symmetry under a periodic driving force and cannot experience an equilibrium state.

“Consequently, local observables exhibit oscillations with a period that is a multiple of the driving frequency, persisting indefinitely in perfectly isolated systems. This subharmonic response represents a spontaneous breaking of discrete time-translation symmetry, analogous to the breaking of continuous spatial symmetry in conventional solid-state crystals,” the authors of the new study explain.