Recent decades have witnessed rapid advancements in high-intensity laser technology. The combination of laser irradiation and novel materials is opening exciting avenues for the design of functional materials and devices. Semiconductors are ideal platforms for generating laser-driven functionalities because they can exhibit novel features such as ultrafast optical transparency. This effect arises from electronic occupation redistribution driven by ultrafast excitation, which manifests as a phenomenon called transient Pauli blocking.

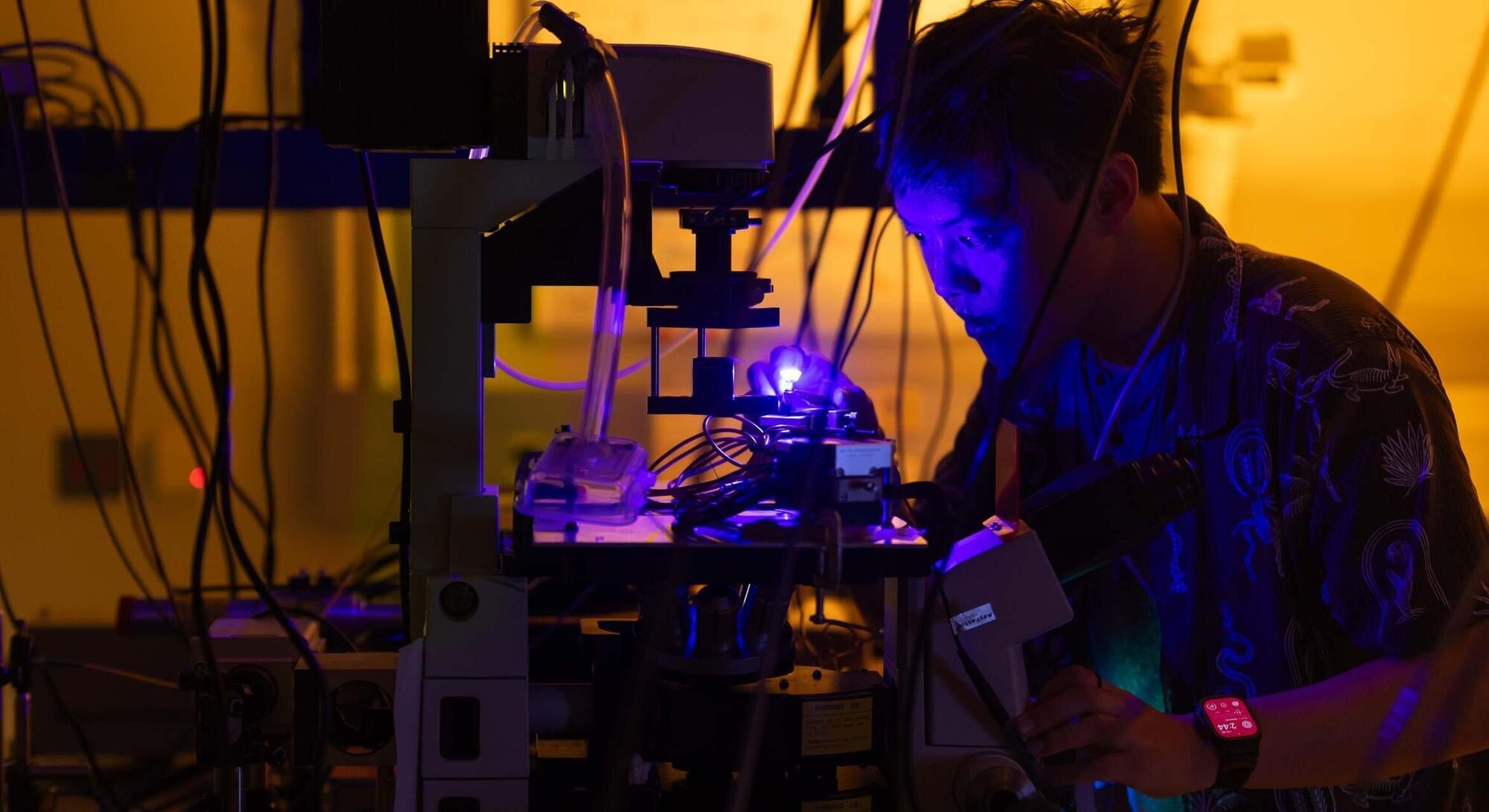

In a new development, a team of researchers in Japan, led by Professor Junjun Jia from the Global Center for Science and Engineering and the Graduate School of Advanced Science and Engineering at Waseda University, has examined the transient Pauli blocking effect in an InN film.

The study utilized pump-probe transient transmittance measurements with multicolor probe lasers, alongside first-principles electronic band-structure calculations. Their findings are published in Physical Review B.