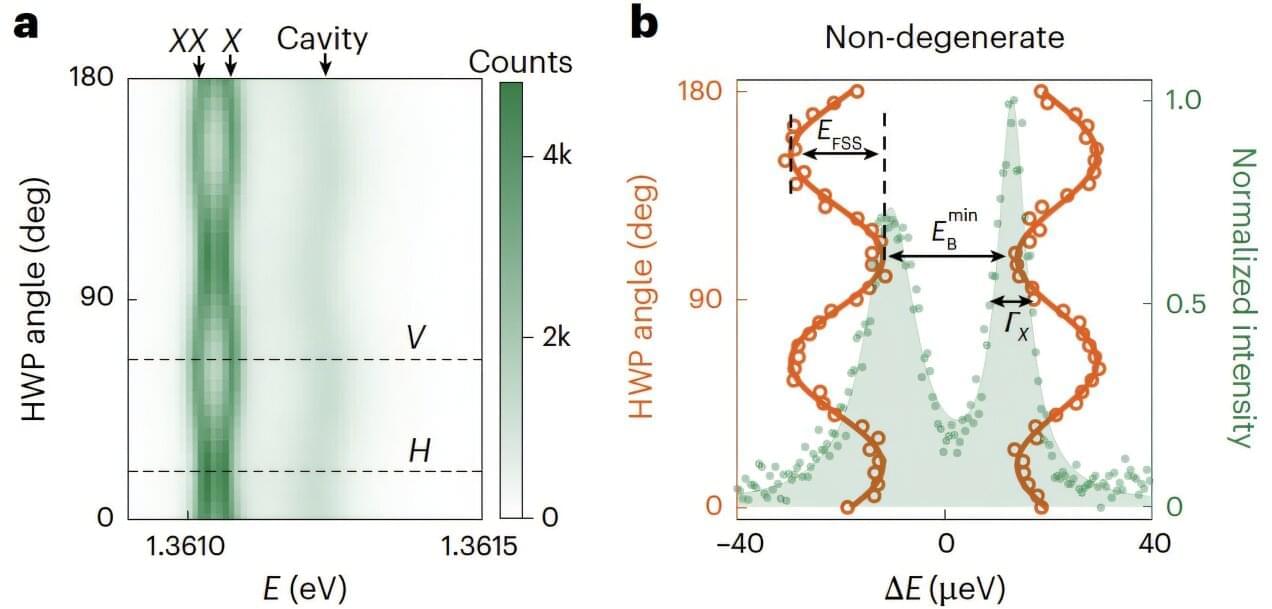

For the first time, researchers in China have demonstrated how quantum dots can be engineered to consistently generate pairs of entangled photons. By carefully tailoring the photonic environment surrounding a single quantum dot, the team showed that it is possible to produce highly correlated photon pairs with remarkable efficiency, potentially opening new opportunities for emerging quantum technologies. The work, led by Zhiliang Yuan at the Beijing Academy of Quantum Information Sciences, is reported in Nature Materials.

In recent years, technologies capable of generating single photons on demand have advanced at an impressive pace. Already, these sources have led to substantial progress in fields ranging from quantum computing and secure communications, to advanced sensing and biomedical imaging.

A natural next step will be the ability to produce pairs of photons that are identical and strongly entangled. Even when separated by large distances, the properties of entangled photons remain linked: an effect that lies at the heart of many quantum technologies.