Immortalist Utilitarianism

Step 1: Seeking Peak Experiences

Ever have a moment in your life that made you feel like jumping for joy, or crying in happiness? Many claim that these are the moments that make life worth living, or at least a lot of what life is about. It’s that moment where you finish writing a book, get a big promotion, or share an intimate moment with someone special.

How many “typical” days would you give for a single moment like that? Some might say 1, others 10, others even 100 or more. Think about it — in a usual day, we’re conscious for around 14 hours. Let’s be conservative and suggest that the average John Doe would trade 5 typical days in exchange for a peak experience that lasts 5 minutes. The time ratio is about 1000:1, but many would still prefer the peak experience over the same old stuff. Unique experiences are really valuable to us.

This would imply that most people value life not only for the length of time they experience, but for the special moments that, as I mentioned earlier, “make life worth living”. As the stereotypical quote goes, “Life is not measured by the number of breaths we take, but by the moments that take our breath away.” Ethicists sometimes quantify such satisfaction as “utility” for the sake of thought experiments; we might say that each 5 minute peak experience is worth a thousand utility points, or “utiles”. Correspondingly, each 5 days of typical activity would also count as roughly a thousand utiles, because one would trade one for the other.

Although it may make some of us uncomfortable to quantify utility, our brain is unconsciously performing computations accessing the potential utility of choices all the time, and the model is incredibly useful in the psychology of human decision making and the field of ethics. Please bear with me as I make some assumptions about utility values and probabilities. Note that I acknowledge that two different people will not tag everything with the same utility, nor will they necessarily compute utility mathematically.

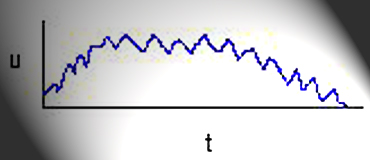

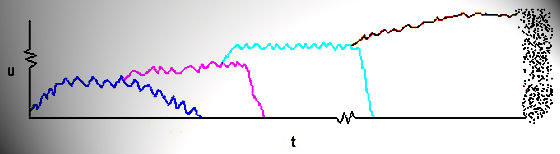

Following is an example of a typical human’s lifelong utility trajectory. It plots utile-moments (u) against time (t). Let’s say that the maximum u value reached is around 200 utiles/minute, or 1000 utiles for the 5 minute peak experience described above. For the sake of simplicity, let’s assume about a hundred 5-minute peak experiences per typical lifetime. Since peak experiences are so fun to have, much of the activity on “typical” days probably entails setting the groundwork for these experiences to happen; ensuring that one does not starve and so on.

The curve rises as the agent has a series of interesting new experiences, plateaus throughout most of adulthood, and subtly falls off in later years, until death is finally reached. It punctuates through peaks and valleys. Some might strongly associate utility with wealth or frequency of sexual activity, others might see utility in their intellectual pursuits.

Total utility: around 6,000,000 utiles, if we figure a lifespan of 80.

Step 2: Avoiding Premature Death

In life there is always the risk of a fatal accident or illness. Death implies an immediate drop-off to the utility curve, a profoundly negative event. That’s why people say stuff like “I’m too young to die!”, or “I can’t stop fighting, I have so much to live for”. Humans despise death, because death sucks. People are willing to go out of their way to avoid it, and rightly so. Some even assert that their lives are the most important thing in the world to them, but I wouldn’t go that far personally.

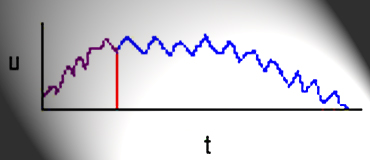

Let’s introduce another aspect into the model. Say event X occurring at the 20-year mark has a probability 10% of eliminating all future experiences, which means a risk of 4,000,000 utiles. In qualitative terms, this would translate into emotional, heart-wrenching arguments like those quoted above. There are some things that people would be willing to give their life for. Just not too many.

Death is a horrible thing if it stands in the way of living a long and fulfilling life. Therefore, it seems like a good idea to take actions to avoid event X if at all possible. Actions and thoughts leading to the avoidance of X have high utility; they are desirable in the same way that setting the groundwork for the a peak experience is desirable. That’s why we are so grateful when someone saves our life, and why we never drive under the influence after that one close call.

The two possible trajectories after the decision instance are represented by red and blue lines. If we die, experienced utility drops to zero immediately. If we survive, it’s business as usual; a life of fun experiences and growth to look forward to. The purple line represents the curve before it splits.

Total utility of blue trajectory: same as above, around 6,000,000 utiles.

Total utility of red trajectory: around 2,000,000 utiles.

Total expected utility of blue trajectory at decision instance:

4,000,000 utiles.

Total expected utility of red trajectory at decision instance: 0

utiles, immediate death.

Since the event only has a 10% chance of killing us, we might not fight against it as hard as an event with 90% chance of death. Some people engage in extreme sports or other risky activities because they see the thrill as worthwhile. But I strongly doubt many of these people would ever engage in an activity with a 5% or greater risk of death, for example. Unless you are completely suicidal, it just isn’t worth the cost.

I’m sure you can imagine the utility trajectories for events such as lethal illness, serious injury, and so on. These things really suck, so people devote a lot of effort to avoiding them, which makes sense. Our society revolves around preventing these negative occurrences, or at least minimizing their probability.

Step 3: Life Extension

It has been shown that cigarette smoking often correlates to shorter life. It has also been shown that good nutrition, specific genes, and regular exercise all contribute predictably to longer lifespan. Hundreds of thousands of years ago, the average human lifespan was around 20, today it’s around four times longer; 80. Isn’t that great?

We’re able to have many more interesting experiences per typical life because our average lifespan has increased so greatly. This leads us to the notion that extending one’s lifespan is a worthy focus, a convenient path to increasing one’s total future utility (fun experiences, growth, etc). We don’t appreciate how lucky we are to live 80 years rather than a mere 20. Our Western culture is accustomed to these longer lifespans.

It’s now considered normal to live such long lives, so our default frame of reference tends to settle there. We should realize how spoiled we are relative to our ancestors, but also how transient our lives might be from the perspective of a person with a much longer life or more fulfilling experiences. As far as we know, there are no such persons in 2004, so we have no comparisons for the moment.

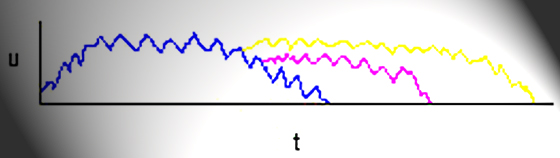

Say we want to add 5 years to our life by quitting cigarettes. This would imply that we value long life more than the short-term pleasure of a nicotine buzz. We may consider the experiences and learning we could gain as a result of this wise decision. We will have displayed the maturity to choose long-term benefits over short-term ones; some people might call this “wisdom”. I’m sure you can visualize the various utility trajectories and the desirability of choosing between them, but here is a picture anyway:

Imagine the blue curve as a cigarette smoker, the pink as a non-smoker who doesn’t exercise, and the yellow as the best possible scenario; a non-smoker who exercises. The yellow trajectory includes the most fun experiences, and the most growth. Total utility is greater.

Here’s where I start talking about potential sources of utility you may not be familiar with.

Say that I have a few friends who offer to preserve the physical structure of my entire body in a deep freeze immediately after my heart stops, and keep frozen until medical science is able to revive me safely. Let’s say my friends happen to be employees of the Alcor Life Extension Foundation, and they’ve been doing these cryonic suspensions for years. Their services are relatively cheap — life insurance pays for the suspension as long as you pay the bills while you are alive.

There are a series of risks — the cryonics company could go out of business, nuclear war might occur, civilization could collapse, your brain decay might be too severe to reverse, and so on. But there is potentially an immense benefit. If a civilization has the technology and desire to revive a freshly preserved frozen body, then that same civilization probably has a great degree of control over biological processes in general.

Aging occurs in humans because ordinary biological processes produce byproducts that the body fails to remove completely. So they build up in the body, causing decay. Keep in mind that most byproducts are removed, only a small percentage of the total remains. But that is enough to cause aging. Stopping aging is a matter of amplifying the human ability to self-regenerate — that is all. There is no mysterious mechanism that forces all organisms to perish at a certain age in order to comply with some Cosmic Order. Ensure that the byproducts of our biology are contained and removed, or not produced in the first place, and you have cured aging.

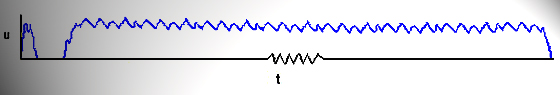

So we are faced with the decision posed to us by our friends, “would you like to sign up for cryonics, or not?” Let’s say we’re being extremely conservative, and only estimate the likelihood of a successful future revival at 0.1%. Let’s say furthermore that our estimate of successful elimination of aging after the initial revival is only 10%, remaining conservative. But if revival and the aging cure are both successful, then let’s say we figure our lifespan could be as long as 10,000 years, at which point we expect some random cosmic accident or war will wipe us out.

Even though the civilization we are talking about probably has extensive control over all biological processes and extremely advanced technology, let’s say our quality of life doesn’t go much further above that which we experienced during our prime — a steady fluctuation of peak experiences and typical days. We also assume that one doesn’t get bored during those ten thousand years, which shouldn’t be too hard if the civilization is developing technologically and has plenty of new stuff to do. Many sci-fi, anime, and fantasy characters have lifespans on this scale, and they seem to be doing fine, so how hard could it be, right?

So, what kind of utility function might a successful cryonics patient have? Maybe something like that shown below. The curve dips down to zero when the patient is frozen solid, and quickly jumps back up after revival. (The squiggly line on the time axis implies that around ten thousand years passes during that time.) Notice the massive potential for extremely long life after revival based on relatively conservative assumptions. The estimated probability of revival needs to be considered separately from the potential benefits.

Total utility of complete trajectory: a whopping 750

million!

Much more

impressive than a mere 6 million, isn’t it?

From the perspective of the pre-cryonics human being, experiencing the huge 10,000-year future lifespan is not certain. As we said; the estimation of successful revival is only 0.1%, and the estimation of an aging cure is 10%. Combine these, and we get an aggregated probability estimate of 0.01% that the whole thing will work at all. So we divide the expected utility of the outcome, 744 million utiles, by our probability estimate, 0.01%. The result is 74,400 utiles only.

But what if paying our life insurance isn’t that big of a deal to us, and the opportunity cost of the lost money only works out to 10,000 utiles or so? In that case, it would make sense to buy life insurance and sign up for cryonics – the expected utility exceeds the projected cost!

If the scenario matches that described above:

Total utility of “yes” answer: 6,074,000 utiles.

Total utility of “no” answer: 5,990,000 utiles.

Many people have made that decision. They tend to be well educated, successful, scientifically literate, and intelligent. Here is a short list by Ralph Merkle, plus a longer study of attitudes toward cryonics by W. Scott Badger. If our estimate of the probability of success goes up from 0.1%, the utility trajectories diverge even farther, and saying “yes” to cryonics seems to be an extremely compelling choice. The prospect of cryonics can contain a massive amount of expected positive utility.

Step 4: Extending Life for Everyone, Not Just Yourself

Stuff like cryonic suspension, regular exercise, good health, and so on, only apply to you. Other people don’t benefit from these practices. Some of us care about humanity as a whole rather than just ourselves, our nation, or our clique, so we devote effort to technologies with the potential to grant more life to wide numbers of people.

For example, respected Cambridge biogerontologist and co-founder of the Methuselah Mouse Prize, Aubrey de Grey, would like to extend the healthy human lifespan an order of magnitude or more beyond its current limits within the next twenty to forty years. Yes, this is a serious strategy for workable anti-aging. He explains fully on his website, please feel free to read it thoroughly. From his proposed Institute outline, de Grey seems to be suggesting that a cure for human aging may come with a price tag of only $10–100m. Not so bad for the benefits, huh?

Let’s say that you continue experiencing 1,000 utiles per 5 days of normal living, but also experience an additional 1 utile per 5 days for every 1,000 people whose lives are extended when they would have otherwise been snuffed out at the arbitrary age of 80 or whatever. “Added years” that people only get to experience as a result of this extreme life extension.

If you feel that the success of de Grey’s Institute will lead to an anti-aging therapy available to millions within the first decade of its release and billions within the third with a probability of, say, 25%, then contributing to this effort would be well worth the time and money. Since you care about each individual person that gets to experience the benefits of added life, it means a lot to you to raise the probability that the necessary anti-aging technology is widely available before they fall to the injustices of aging and premature death.

On his website, Aubrey mentions lifespans that exceed 5,000 years. So, if the Institute is successful, then let’s assume that translates into around five million people with five-millennia lifespans shortly after the technology is invented, around five hundred million people with lifespans of that length a decade after, and five billion people two decades after.

Considering the fast global adoption of technologies such as the Internet and cell phones, this distribution pattern seems extremely conservative. People would surely be willing to focus on buying a drug that extends one’s lifespan to 5,000 healthy years or more. Possibly it could be a one-time thing, or “booster shots” might be required every few decades for negligible cost.

So, you find yourself with a million dollars. You can either buy a mansion or contribute the money to aging research. Your assumptions are roughly in line with those outlined above; you have examined Aubrey de Grey’s arguments in detail and regard them as valid. The lives of other human beings are important to you and you feel satisfaction when their lives are extended. You want to compute the expected utility of both outcomes; how does the math work out?

- Say $1,000,000 is about 2% of the Institute’s total financial requirements.

- So you are contributing 2% of the effort toward the Institute’s success.

- If success is achieved, about five million people immediately get an extra 10 years of life.

- Every five days, you would get an extra 5,000 utiles in addition to the usual 1,000.

- After another decade, five hundred million people have the drug.

- That means five million more utiles per five days.

- After yet another decade, five billion people have it – half of Earth’s projected population.

- You get fifty million utiles per five days.

- Let’s say you feel the satisfaction for a total of another five decades before you get used to it.

- (When you get used to it, it becomes the new status quo, not really providing utility anymore.)

- Five decades times fifty million utiles per five days is… a lot.

At this point our results may look a little odd and we will question the original utilitarian assumptions. The point of this thought experiment is not really to encourage you to formalize your ethical system as a set of utility values and probabilities, but to convey the huge value of extending the human life span for millions or billions of people.

Gandhi, MLK, or the inventor of the polio vaccine couldn’t possibly have imagined a good deed on this scale. Giving huge lifespans to humans that want them is an action with huge utility, unless the whole thing backfires due to population problems. (Unlikely due to the availability of clean manufacturing processes, efficient habitats, and cheap space travel. See “Will extended life worsen overpopulation problems?”)

So, the resulting utility graph is a bit more complicated:

Total expected utility of donation: massive; billions of utiles

or more.

Total expected utility of a mansion: not nearly as

much.

Utility goes up more and more as additional lives are saved. This graph assumes that one considers the lives of all those living after his or her life to be meaningless. In real life, people often feel otherwise. The fuzziness of to the right side of the graph represents our uncertainty about the long-term consequences — 5,000 years may turn out to be a ridiculously low estimate, and our real lifespans may lie in the realm of the millions or even billions — who knows! If there are no huge cosmic disasters, no war, and you can repair yourself or back up your memories at a whim, who’s to say that your lifespan won’t be as long as that of the universe?

You’ll also notice that the utility axis has been expanded in the upward direction. That’s because contributing to the extended life of millions or billions of people is (presumably) a bigger deal than only extending your own life. Engineering the human brain to better experience pleasure may be another may to increase total utility, or perhaps through enhancing our intelligence, empathy, creativity, and so on. These speculations are the province of transhumanism. Feel free to read up on the topic if you’re interested in learning more. See also the question on the FAQ, “Won’t it be boring to live forever in the perfect world?”

Step 5: Threats to Everyone — Existential Risk

The value of contributing to Aubrey de Grey’s anti-aging project assumes that there continues to be a world around for people’s lives to be extended. But if we nuke ourselves out of existence in 2012, then what? The probability of human extinction is the gateway function through which all efforts toward life extension must inevitably pass, including cryonics, biogerontology, and nanomedicine. They are all useless if we blow ourselves up.

At this point one observes that there are many working toward life extension, but few focused on explicitly preventing apocalyptic global disaster. Such huge risks sound like fairy tales rather than real threats — because we have never seen them happen before, we underestimate the probability of their occurrence. An existential disaster has not yet occurred on this planet.

The risks worth worrying about are not pollution, asteroid impact, or alien invasion — the ones you see dramatized in movies — these events are all either very gradual or improbable. Oxford philosopher Nick Bostrom warns us of existential risks, “…where an adverse outcome would either annihilate Earth-originating intelligent life or permanently and drastically curtail its potential.”

Bostrom continues, “Existential risks are distinct from global endurable risks. Examples of the latter kind include: threats to the biodiversity of Earth’s ecosphere, moderate global warming, global economic recessions (even major ones), and possibly stifling cultural or religious eras such as the “dark ages”, even if they encompass the whole global community, provided they are transitory.”

Four Main Existential Risks

The four main risks we know about so far are summarized by the following, in ascending order of probability and severity over the course of the next 30 years:

Biological. More specifically, a genetically engineered supervirus. Bostrom writes, “With the fabulous advances in genetic technology currently taking place, it may become possible for a tyrant, terrorist, or lunatic to create a doomsday virus, an organism that combines long latency with high virulence and mortality.” There are several factors necessary for a virus to be a risk. The first is the presence of biologists with the knowledge necessary to genetically engineer a new virus of any sort. The second is access to the expensive machinery required for synthesis. Third is specific knowledge of viral genetic engineering. Fourth is a weaponization strategy and a delivery mechanism. These are nontrivial barriers, thankfully.

Nuclear. A traditional nuclear war could still break out, although it would be unlikely to result in our ultimate demise, it could drastically curtail our potential and set us back thousands or even millions of years technologically and ethically. Bostrom mentions that the US and Russia still have huge stockpiles of nuclear weapons. Miniaturization technology, along with improve manufacturing technologies, could make it possible to mass produce nuclear weapons for easy delivery should an escalating arms race lead to that. As rogue nations begin to acquire the technology for nuclear strikes, powerful nations will feel increasingly edgy.

Nanotechnological. The Transhumanist FAQ reads, “Molecular nanotechnology is an anticipated manufacturing technology that will make it possible to build complex three-dimensional structures to atomic specification using chemical reactions directed by nonbiological machinery.”

Because nanomachines could be self-replicating or at least auto-productive, the technology and its products could proliferate very rapidly. Because nanotechnology could theoretically be used to create any chemically stable object, the potential for abuse is massive. Nanotechnology could be used to manufacture large weapons or other oppressive apparatus in mere hours; the only limitations are raw materials, management, software, and heat dissipation.

Human-indifferent superintelligence. In the near future, humanity will gain the technological capability to create forms of intelligence radically better than our own. Artificial Intelligences will be implemented on superfast transistors instead of slow biological neurons, and eventually gain the intellectual ability to fabricate new hardware and reprogram their source code. Such an intelligence could engage in recursive self-improvement — improving its own intelligence, then directing that intelligence towards further intelligence improvements. Such a process could lead far beyond our current level of intelligence in a relatively short time. We would be helpless to fight against such an intelligence if it did not value our continuation.

Conclusion

So let’s say I have another million dollars to spend. My last million dollars went to Aubrey de Grey’s Methuselah Mouse Prize, for a grand total of billions of expected utiles.

But wait — I forgot to factor in the probability that humanity will be destroyed before the positive effects of life extension are borne out. Even if my estimated probability of existential risk is very low, it is still rational to focus on addressing the risk because my whole enterprise would be ruined if disaster is not averted. If we value the prospect of all the future lives that could be enjoyed if we pass beyond the threshold of risk — possibly quadrillions or more, if we expand into the cosmos, then we will deeply value minimizing the probability of existential risk above all other considerations.

If my million dollars can avert the chance of existential disaster by, say, 0.0001%, then the expected utility of this action relative to the expected utility of life extension advocacy is shocking. That’s 0.0001% of the utility of quadrillions or more humans, transhumans, and posthumans leading fulfilling lives. I’ll spare the reader from working out the math and utility curves — I’m sure you can imagine them. So, why is it that people tend to devote more resources to life extension than risk prevention? The follow includes my guesses, feel free to tell me if you disagree:

They estimate the probability of any risk occurring to be extremely low.

- They estimate their potential influence over the likelihood of risk to be extremely low.

- They feel that positive PR towards any futurist goals will eventually result in higher awareness of risk.

- They fear social ostracization if they focus on “Doomsday scenarios” rather than traditional extension.

Those are my guesses. Immortalists with objections are free to send in their arguments, and I will post them here if they are especially strong. As far as I can tell however, the predicted utility of lowering the likelihood of existential risk outclasses any life extension effort I can imagine.

I cannot emphasize this enough. If a existential disaster occurs, not only will the possibilities of extreme life extension, sophisticated nanotechnology, intelligence enhancement, and space expansion never bear fruit, but everyone will be dead, never to come back. Because the we have so much to lose, existential risk is worth worrying about even if our estimated probability of occurrence is extremely low.

It is not the funding of life extension research projects that immortalists should be focusing on. It should be projects that decrease the risk of existential risk. By default, once the probability of existential risk is minimized, life extension technologies can be developed and applied. There are powerful economic and social imperatives in that direction, but few towards risk management. Existential risk creates a “loafer problem” – we always expect someone else to take care of the problems. I assert that this is a dangerous strategy and should be discarded in favor of making prevention of such risks a central focus.

Organizations

Organizations explicitly working to prevent existential risk:

Center for Responsible Nanotechnology

Advanced nanotechnology can build machines that are thousands of times more powerful — and hundreds of times cheaper — than today’s devices. The humanitarian potential is enormous; so is the potential for misuse. The vision of CRN is a world in which nanotechnology is widely used for productive and beneficial purposes, and where malicious uses are limited by effective administration of the technology. An important organization doing genuinely valuable, positive work.

Singularity Institute for Artificial Intelligence

The Singularity Institute for Artificial Intelligence is a nonprofit corporation dedicated solely to the technological creation of greater-than-human intelligence. The Singularity Institute sees no reason why we won’t be able to eventually build such intelligences — it basically burns down to an engineering problem. If the first greater-than-human intelligence were a benevolent one, it could use its intelligence to further improve its own intelligence, the intelligence of human beings, and assist others in the pursuit of humanitarian causes.

And, of course, the Lifeboat Foundation, one of the most important organizations of the early 21st century, has many programs to reduce existential risk.

Thank you for your attention!

Michael Anissimov