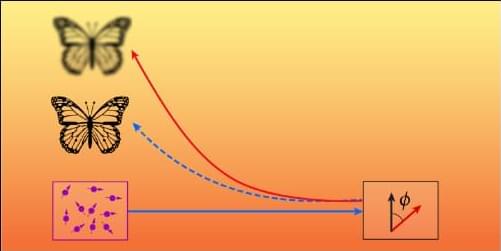

A long-standing law of thermodynamics turns out to have a loophole at the smallest scales. Researchers have shown that quantum engines made of correlated particles can exceed the traditional efficiency limit set by Carnot nearly 200 years ago. By tapping into quantum correlations, these engines can produce extra work beyond what heat alone allows. This could reshape how scientists design future nanoscale machines.

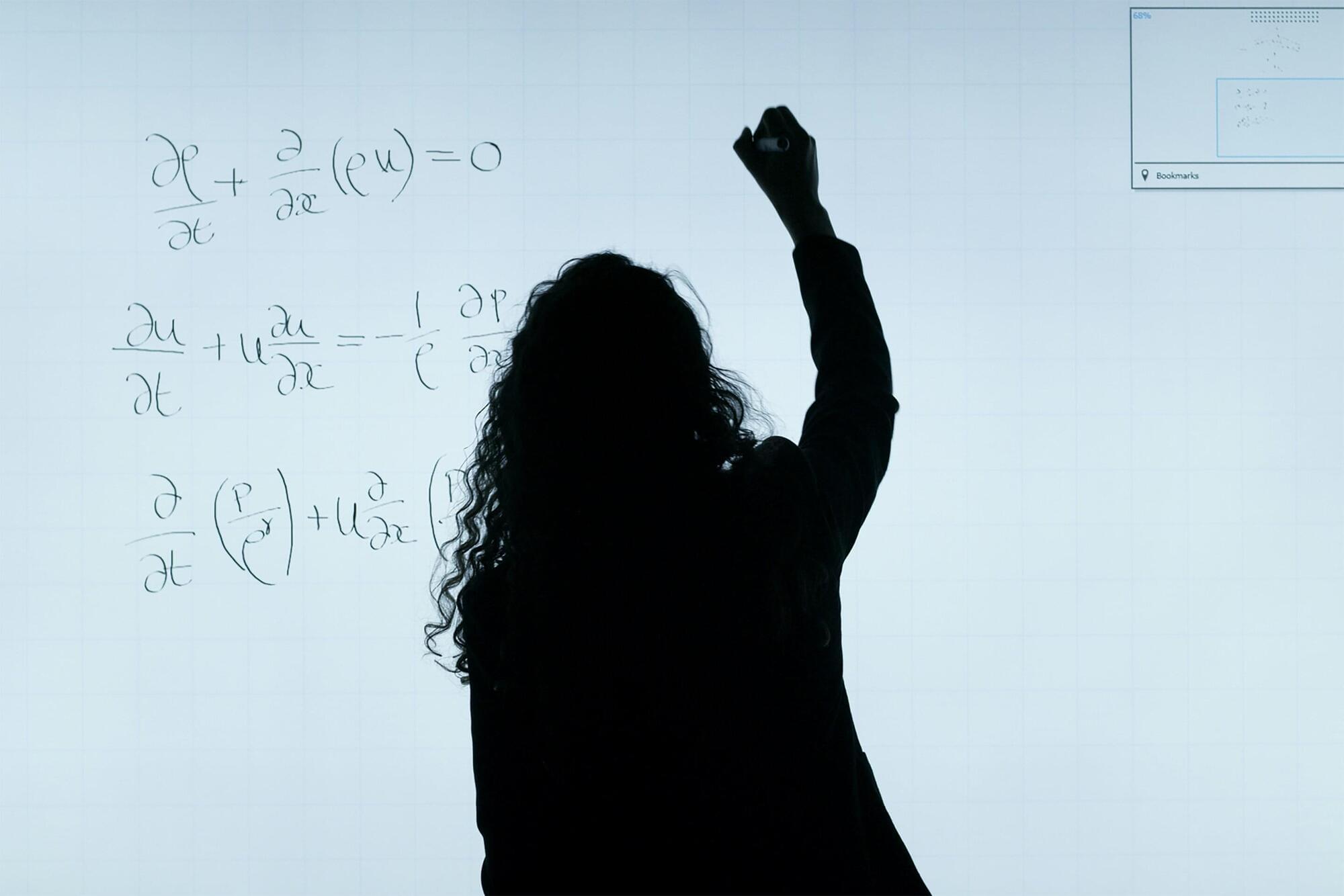

Two physicists at the University of Stuttgart have demonstrated that the Carnot principle, a foundational rule of thermodynamics, does not fully apply at the atomic scale when particles are physically linked (so-called correlated objects). Their findings suggest that this long-standing limit on efficiency breaks down for tiny systems governed by quantum effects. The work could help accelerate progress toward extremely small and energy-efficient quantum motors. The team published its mathematical proof in the journal Science Advances.

Traditional heat engines, such as internal combustion engines and steam turbines, operate by turning thermal energy into mechanical motion, or simply converting heat into movement. Over the past several years, advances in quantum mechanics have allowed researchers to shrink heat engines to microscopic dimensions.