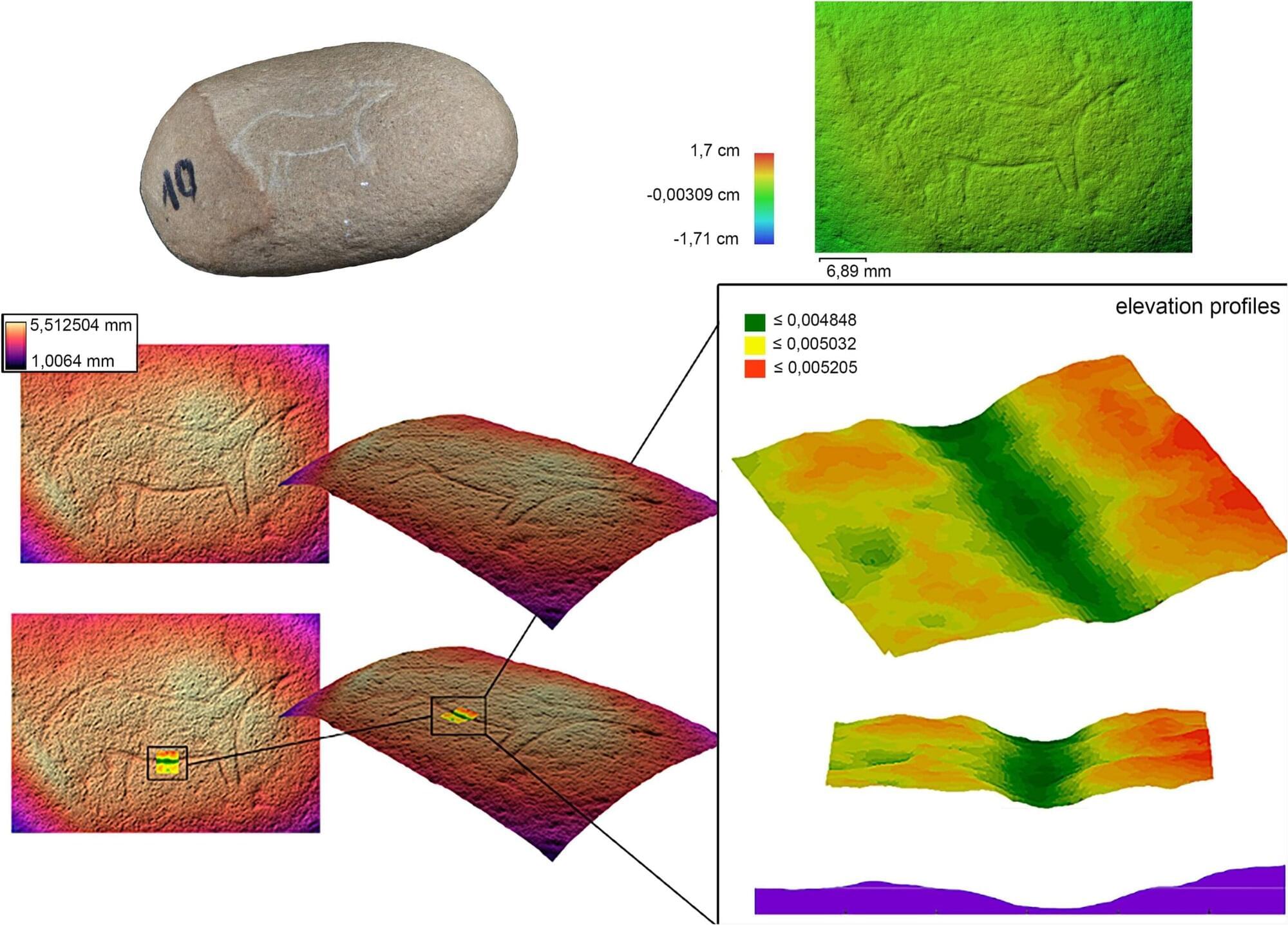

A team of archaeologists from the Universitat Jaume I, the University of Barcelona, and the Catalan Institution for Research and Advanced Studies (ICREA) has developed a new methodology that allows for a much more detailed, precise, and objective analysis of Late Paleolithic portable art pieces. Thanks to this study, the research team was able to review several previously published pieces from Matutano Cave (Vilafamés), a reference site in the Iberian Mediterranean, with greater accuracy and demonstrate that some of the marks previously interpreted as artistic motifs are not anthropic engravings but natural surface reliefs.

Late Paleolithic art is usually characterized by very fine engravings, barely visible to the naked eye, often affected by taphonomic alterations, surface irregularities, and unclear morphologies, which complicates their identification and interpretation. This new methodology allows for a more precise analysis of the remains using photogrammetry and microtopographic analysis techniques.

The results are published in the Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports.